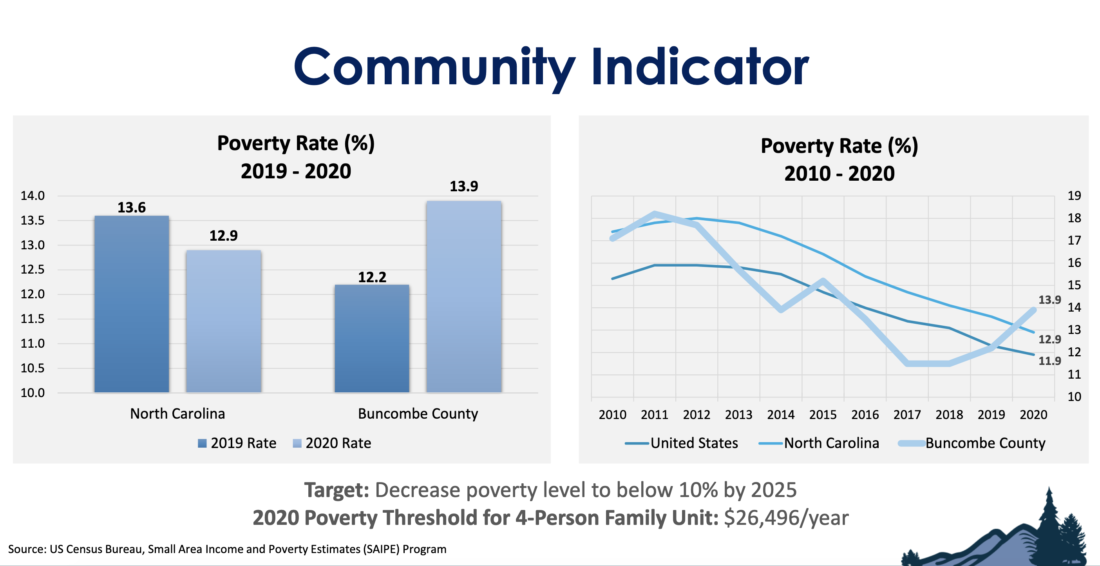

Even as poverty rates in North Carolina and across the U.S. have steadily declined, the percentage of Buncombe County residents experiencing poverty has been increasing since 2018.

That was a key takeaway from the county Board of Commissioners briefing Aug. 2 as staff members updated the board about the “vibrant economy” focus area of Buncombe’s Strategic Plan 2025.

According to data presented by Tim Love, Buncombe’s director of economic development and governmental relations, the county’s poverty rate went up from about 11.5% in 2018 — its lowest point in a decade — to about 13.9% in 2020, the latest year for which information was available. In contrast, North Carolina’s poverty rate decreased from about 14% to 12.9% over the same period; the U.S. rate fell from approximately 13.1% to 11.9%. (A family of four must earn $26,496 or less annually to qualify as being in poverty.)

More recently, noted Love, median wages in the county have been going up, increasing by 71 cents per hour between May 2021 and this May to reach $27.32. However, that increase was less than half the $1.76 bump recorded statewide over the same period, and the median North Carolina hourly wage of $29.59 is also higher than Buncombe’s.

Commissioners asked staff to break out the data in more detail to better understand what was driving Buncombe’s rising poverty rates.

Board Chair Brownie Newman asked what percentage of families experiencing poverty were employed and how much they bring in each week, noting that the county’s unemployment rate of 3% was very low. Other commissioners were interested to see the number of dependents each family had, how the data broke down by race and whether an exodus of working mothers from the workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic had impacted the poverty rate.

“This is why we wanted to present this,” said Love. “There’s different stories to tell, and the reality is that at the end of the day, these are the numbers that matter, so we have to drill into those.”

Buncombe staffers had better news regarding other strategic plan targets. The county is on track to achieve its stated goals of implementing land use strategies that encourage affordable housing near transportation and jobs and increasing total employment in specific industries.

Progress has also been made in infrastructure projects expected to improve economic development. The bridge connecting Smokey Park Highway to Enka Commerce Park is scheduled to be completed by the end of the year, and the bridge to Biltmore Park West, which provides access to the Pratt and Whitney site from Brevard Road, has been completed and will open later this year.

Meanwhile, six applications from five different internet providers have been submitted for federal funding through the Growing Rural Economies with Access to Technology Grant program. The initiative is meant to support expansion of broadband service to areas that currently don’t have access. The county anticipates that at least one of those grants will be awarded, with hopefully one or two more being awarded funding through the state’s Completing Access to Broadband program.

If all six applications were funded, said Love, about 7,000 Buncombe households would get broadband access. He noted that both grant programs will repeat next year, offering another chance for all six projects to be funded.

Commissioners support Kuwohi name change for Clingmans Dome

During their meeting later Aug. 2, commissioners unanimously voted in favor of a resolution to support the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians in its efforts to restore the original Cherokee name of Kuwohi to Clingmans Dome. The current name of the mountain — the highest in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park — honors Confederate general and explorer Thomas Lanier Clingman. The Cherokee name translates to “the place of mulberries.”

Four people spoke on the topic during public comment, all in favor of the name change.

“I’m a dual citizen of the Cherokee Nation as well as the United States, my family survived the removal along the Trail of Tears to Oklahoma, and my grandfather is a boarding school survivor,” said Asheville resident Jared Wheatley. “This type of restoring a name to our ancestral language goes beyond just a signal of importance. It also speaks to recognizing the community that still exists in Western North Carolina.”

Commissioner Parker Sloan, who brought the resolution to the board, said that the culture and language of the EBCI had survived through its members’ determination over the years, despite forced attendance at boarding schools that sought to erase their language. The EBCI’s Tribal Council had voted July 14 to send a resolution to the U.S. Department of Interior requesting the name change. Sloan said that displays of local government and community support for the change would be an important factor in the federal government’s decision.

Before voting, Sloan asked EBCI representatives whether the pronunciation and spelling of the Cherokee name were correct. Lavita Hill noted that the tribe’s Speakers Council had verified that Kuwohi (ᎫᏩᎯ in Cherokee script) should be transliterated with an “o” instead of an “a,” as it had been originally spelled in the board’s resolution.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.