Licensed clinical social worker Elizabeth Endres recalls a particular patient who declined resources for addressing substance misuse many times. But as the mental health provider for Appalachian Mountain Health’s mobile medical unit, Endres was frequently in the patient’s residential community, providing counseling and support to other individuals. So she was often able to reconnect with that same patient and repeat her offer for services.

Then one day recently, Endres says, “she came straight up to me, and she said, ‘I’ve had enough, I want to go to detox. Talk to me about my options.’”

That is exactly how a mobile medical unit is supposed to work: meeting people where they are — both figuratively and literally — so that medical care is accessible when they need it.

There are many reasons people cannot or do not access medical care. Some, like Endres’ patient, aren’t ready to address a health issue. For others, visiting a health care provider presents insurmountable barriers. Getting to an appointment often requires a vehicle, a ride to the medical office or an internet connection, quiet and privacy. Filling out health insurance paperwork can take more time than many people have — as long as or longer than the appointment itself. And for an individual living on a low income, the fees for visits and lab tests can be out of reach.

For some, simply entering a medical building may feel impossible for various reasons. Sue Hanlon, nurse supervisor at Buncombe County’s Public Health Mobile Team, notes that sometimes the presence of law enforcement officers in the county’s Department of Human Services building is a barrier, for example.

The result is that many people go untreated. Their primary interaction with a health care provider might only come in a crisis, such as a visit to the emergency room.

The expansion of mobile health units throughout Buncombe County is bringing health care where it is needed most — right to them, with minimal barriers.

“We’re not there to judge,” Endres says. “People come up to us high — it doesn’t matter, I’m gonna [see them]. We’re not going to tell them ‘no.’ … We just want people to get healthier. There should be nothing interfering with that.”

‘Wow, this is for free?’

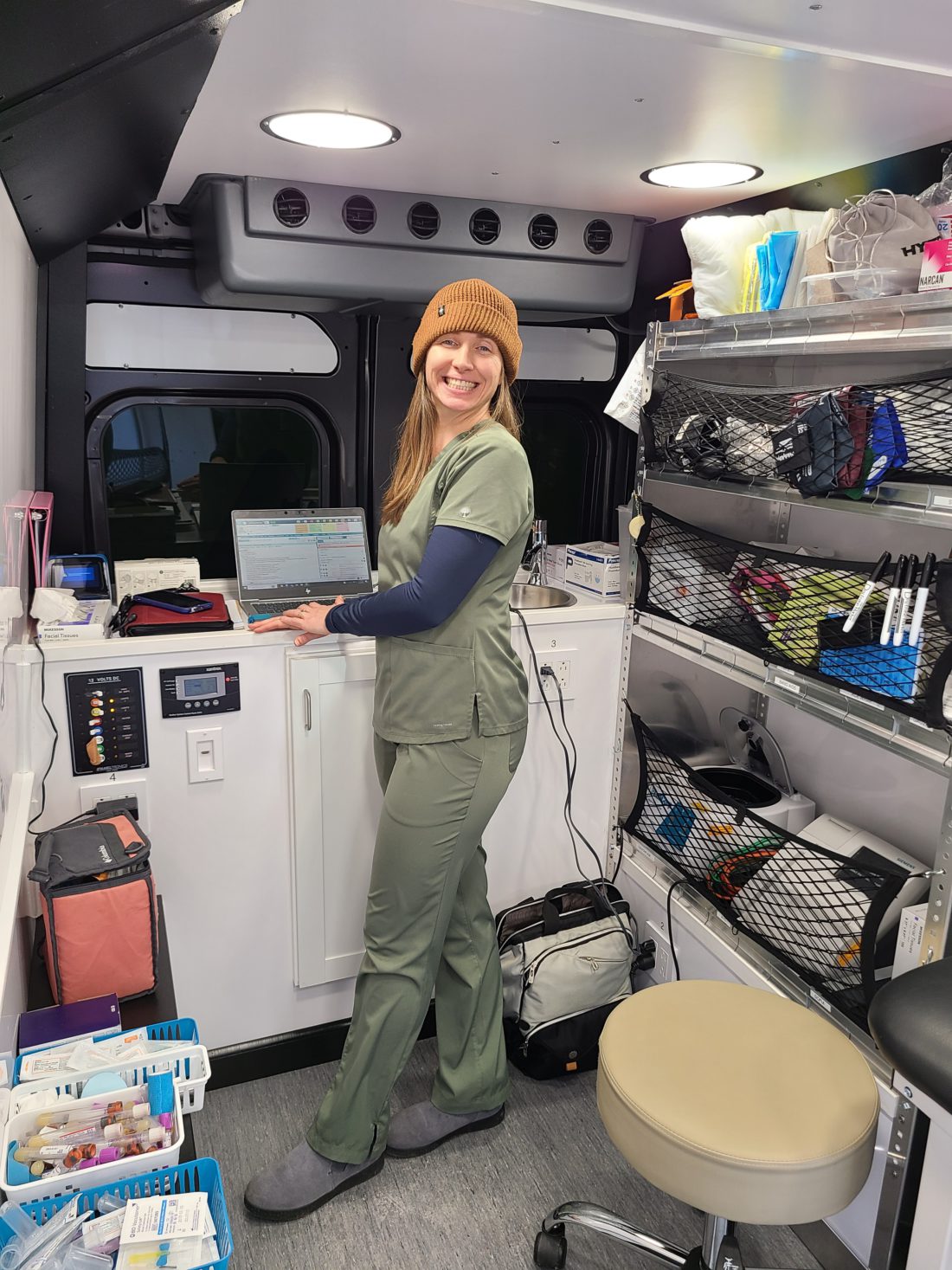

Appalachian Mountain Health (formerly known as Appalachian Mountain Community Health Centers) debuted its mobile medical unit within the past year. The mobile medical unit has a van carrying wound care supplies, one-time doses of antibiotics, a blood pressure monitor, supplies for urine tests, and hygiene products like detergent, shampoo and menstrual products. Sometimes the team hands out blankets. The van reaches patients who live in underresourced communities, including public housing developments like Pisgah View Apartments; a permanent supportive housing facility, Compass Point Village; and a transitional housing facility for women and children, Transformation Village. It also visits people who are unhoused.

The team includes: Endres, who addresses mental health; community resource advocate Doris Bennett, who assists people with navigating resources, such as signing up for Medicaid; and family nurse practitioner Summer Hettinger, who addresses primary care issues.

Health problems related to chronic issues like diabetes are common among her patients, Hettinger says. She often treats wounds, which sometimes come from substance use. She can also conduct screenings and provide tests for influenza and COVID-19. Most medical appointments are about 20-30 minutes long, she says, and the behavioral health appointments can run to 45 minutes.

Buncombe County Department of Health and Human Services has a mobile medical unit dedicated to public health, rather than primary care. The Public Health Mobile Team is composed of three public health nurses, an emergency management specialist and an administrative assistant. Its van visits community centers like Linwood Crump Shiloh Community Center, libraries, the YMCA, schools — such as A.C. Reynolds Middle School on community night — and residences like the Villas at Swannanoa Senior Apartments. It also focuses on people who are historically underserved by the health care system: those with low incomes and rural communities.

Part of being accessible to the widest swath of community residents is providing services at no cost or low cost, which both the county’s mobile unit and the Appalachian Mountain Health unit do. “No one ever has to pay out of pocket,” says Hanlon of the Public Health Mobile Team’s services. (The county can bill a health insurance provider if a patient has coverage.)

“They’re always so impressed,” says Hanlon of the mobile team’s patients. “‘Wow, this is for free? You all can do this?’”

Who they serve

The Public Health Mobile Team reaches a number of different populations. It works side by side with the Buncombe County Emergency Medical Services’ paramedics, visiting patients in the community room at Haywood Street Congregation, a nonprofit that serves unhoused people. It works in partnership with Poder Emma and UNETE N.C, nonprofits serving the local Latino community. And it can also attend specific events if the demographics meet the criteria for clientele it serves, such as LGBTQ+ individuals at Asheville’s annual Pride celebration. (Its calendar is here: avl.mx/dbo)

Other mobile health units bring specialized services to patients in more rural locales. For example, Four Seasons, a nonprofit providing hospice and palliative care in Hendersonville, debuted a mobile unit last summer that enables it to bring palliative care to patients in the westernmost counties of the state.

The WNC Community Health Services Mobile Unit, which serves all of WNC, offers medical exams for adults and children, school physicals, sports physicals and immunizations. It also provides dental exams and cleanings for adults and children. (WNCCHS is a federally qualified health center, meaning it provides services to patients regardless of their ability to pay.)

Mobile units offer different services and serve different regions or locations, but often there is overlap and even coordination. Appalachian Mountain Health and the Public Health Mobile Team interact with the Buncombe County community paramedics frequently, as they work with some of the same patients.

“If someone decided today was the day that they wanted to receive medication for opioid use disorder, we could make that connection right then and there with the community paramedics,” adds Buncombe County Public Health Director Dr. Ellis Matheson.

Preventive care supports community

The Public Health Mobile Team’s focus is on preventive care — preventing the spread of diseases specifically, explains Matheson.

The unit mainly offers immunizations and testing for sexually transmitted infections, including COVID-19, hepatitis A and B, influenza, shingles, tetanus/TDAP and monkeypox, says Hanlon. It can also provide rapid testing for HIV and Hep C and will link people to appropriate care for those viruses. Though its patients are mostly adults, it can provide pediatric vaccinations for COVID-19 and influenza.

Harm reduction, which is a public health strategy to decrease the negative impacts associated with substance use, is a focus for the Public Health Mobile Team. It provides Narcan, the overdose reversal medication, and test strips for fentanyl and xylazine (also known as “tranq”), all for free.

Matheson notes that when preventive care is not being addressed well — for example, when a virus spreads or a substance causes overdoses — a community becomes more invested in public health as a whole. The rest of the time, when prevention is working, its impact is less seen.

“Public health really is invisible,” she says. “But it’s also important for people to know why what we do is so important.”

Trust

Both mobile units that spoke with Xpress say the most important thing they do is develop trust. And they do that in part by simply being there, again and again. Someone might not visit a van parked on the street the first time they walk by, Hanlon explains. “But we slowly are building trust, because we show up,” she says. “And we show up with kindness and care.”

The key is not pushing anything — services, advice, information — on anyone and “developing this comfort level and knowing I’m not out to get them,” Endres says. A lot of her work to initially gain trust involves just chatting with people. “We talk about their dogs,” she says with a smile. “We give out dog treats now.”

Word-of-mouth is the best advertising, the team at Appalachian Mountain Health has found.

“In Pisgah View Apartments, there were several faces that I already knew from living in the community and working at Dale Fell [an Appalachian Mountain Health clinic in Asheville],” explains Hettinger. Once they learned she would be in the mobile medical unit regularly, “they were like, ‘Oh, I’m going to tell so-and-so!’”

Each community has “these unofficial community advocates” who inform their friends and neighbors about the resources, Endres explains. “Those people are huge” because they signal trust and approval. And they communicate to Appalachian Mountain Health’s team what their community actually needs, which is crucial.

Accessing services on a mobile medical unit can be an on-ramp, if needed, for accessing the higher level of services available in a brick-and-mortar clinic, Hettinger explains.

Big dreams

The biggest challenge of operating out of vans is, not surprisingly, the lack of space.

Appalachian Mountain Health operates out of a van that is about the size of an ambulance. It has a small lab inside it, as well as an exam bed and an EKG machine. Hettinger can meet with patients in the van itself, and she relies on community center partners to give them access to their bathrooms. She appreciates how Compass Point Village and Transformation Village allow her to use indoor spaces at their locations.

The unit also has a smaller vehicle, where Endres can bring patients to sit inside with her on colder days.

The Public Health Mobile Unit sets up an area to see patients in a nearby tent or inside the community building or school where it is stationed. Its supplies — COVID-19 tests, boxes of Narcan, syringes, alcohol swabs, Band-Aids, rapid testing kits — are stored inside the van. “It’s not big enough, and we can’t do everything we want to do,” laments Hanlon. But “we make it work.”

BCDHHS is awaiting the arrival — hopefully in March, Matheson says — of a new RV for the mobile unit that will have enough space to offer a private interview and exam room. She and Hanlon express excitement about having expanded space. “I’m having a ribbon-cutting and inviting the whole world,” Matheson jokes.

Hanlon also says the team is currently being trained on how to initiate contraception for patients, which it’s hoping to offer later this year. And her “pie in the sky” dream, she says, would be for mobile units to provide all services available from BCDHHS, like signing up for Medicare, Medicaid or the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children.

Expansion of the county’s mobile health team could come. “The process that we’re in right now is establishing trust within the community, which is going to allow us to really understand what are those true needs in the different communities — because of course, each community is different,” explains Matheson. “Then once we can understand those needs, we can identify where we want to grow and expand.”

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.