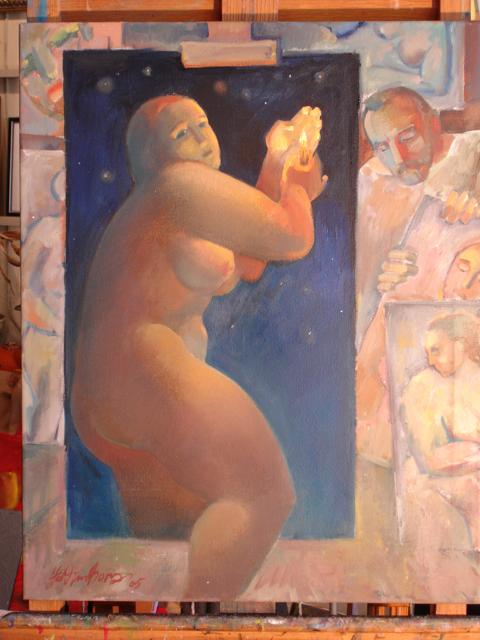

- “Studio at Night”: Bora paints himself into the background, holding portraits, while a voluptuous nude (a favorite subject of the Asheville-based artist) seems to step off of her canvas. All photos courtesy of Constance Richards

- “Stealing the Rooster”: Bora often painted roosters and other scenes from Russian village life. He relocated to Asheville from Vladikavkaz in the Caucasus Mountains in 1993.

- Life-sized and lifelike: A master sculptor as well as painter, one of Bora’s final creations was “Cornelia and Cedric,” a bronze sculpture commissioned by the Biltmore Estate.

- I’ll flay away: Master painter and sculptor Vadim Bora at the Louvre (left). An angel enters a light-filled doorway, leaving behind a lone glass of wine in Bora’s painting “Flying Away.”

Vadim Bora created art even in his sleep. According to his wife, local writer Constance Richards, Bora slept with a sticky note and light-up pen beside his bed and would wake in the night to sketch an idea.

When he went on vacation, he was constantly sketching. Says his son, artist Georgi Bora, the local painter, sculptor and teacher had a goal to fill a sketchbook per week; that's how he mastered line and form. Vadim was never off work — art, for him, was 24/7.

The artist, who came to Asheville from Russia in 1993 and gained U.S. citizenship in 2009 (notably as a “person with extraordinary abilities”), passed away on January 5 following a stroke. Vadim left behind a massive body of work, including many pieces of public art — most recently the bronze sculpture "Cornelia and Cedric" commissioned by the Biltmore Estate for its Antler Village and dedicated last September.

Vadim also left behind legions of family, friends, students, collectors and colleagues, both in Asheville and in his hometown of Vladikavkaz (in Russia’s North Ossetia region of the Caucasus mountains). Memorial gatherings brought together more than 300 people in each city. That’s why Christopher Holt, school director of The Fine Arts League of the Carolinas, says that Vadim's legacy lies in "the ability that an artist has to make a better community."

Sister Cities, family ties

About that community: Vadim's hometown and adopted hometown are Sister Cities — which is how the artist found his way to Western North Carolina. According to Richards, Vadim had met an Asheville delegation to Vladikavkaz during the early ‘90s when that group was invited to visit an artist's studio. Namely, Vadim's. In his 30s at the time, he had an established career as a sculptor and metalworker, designing jewelry and knife sheaths. But, says Richards, "He knew he had a lot to achieve artistically. He knew he wanted his son to have bigger possibilities."

Vadim’s Asheville memorial was recently held at the Diana Wortham Theatre. There, father-in-law Ken Richards recounted a story from Vadim’s childhood. Most kids play in the mud, but young Vadim found some wild clay and sculpted figures of the townspeople accurate enough that the unwitting models recognized themselves. Vadim’s parents weren't artists — his father was a police detective and his mother was a teacher — but they nurtured Vadim's creativity as Vadim, in turn, did for his son Georgi.

One Valentine's Day, when Georgi was in first grade, Vadim asked him if he had a romantic interest. "There was one girl," Georgi recalls. His father said, “Let's go to the studio and make a gift for the girl: a ring.” Vadim instructed his son in the process of jewelry making, and the resulting silver ring was worn all through high school by the girl (who Georgi considers a friend to this day).

"He's done some amazing work,” says Georgi, who notes that Vadim’s art was even commissioned for an Ossetian movie.

When Vadim made the move to the U.S., he chose Asheville because he'd kept in touch with people from the Sister Cities delegation. "Vadim had an eye on going to New York or Chicago," Richards says. (In fact, Vladikavkaz has a population of around 350,000, about five times the size of Asheville.) "But he met people here who were helpful."

He arrived in Asheville at age 39, setting up his studio in the upstairs of the Biltmore Village building that now houses Rezaz Mediterranean Cuisine. Richards — who spent time living and working in Russia and was actually there when Vadim first came to Asheville — says the studio reminded her of St. Petersburg, including intolerable working conditions. Freezing in the winter and boiling in the summer, it drove out nearly all of the other artists. But Vadim, always inventive, customized "air-conditioned" clothing and shoes.

The first time Richards met Vadim was not at that studio, though he invited her. (Later, as a couple, they opened Vadim Bora Studio-Gallery on Battery Park Avenue and, for a time, ran a second gallery out of the Haywood Park Hotel). They were introduced by Richards’ parents at an event for a group of Russian small-business directors, says Richards. Later they met again at a Downtown After Five concert "which then became the date we celebrated."

Celebration was a theme in Vadim's life. At the memorial, a friend from his Boys Night Out group mentioned Vadim's love of ginger-flavored vodka. Holt notes, "He actually liked tequila better than vodka." Anyone who stopped by an opening at Vadim's Battery Park gallery was plied with conversation and wine. Says Holt: "There were no strangers.”

The work of play

So Vadim created community. "Vadim lived a big life," Richards says. But he also created art, and while he was known as an artist, it’s possible that his larger-than-life persona overshadowed the breadth of his work.

Local painter Julyan Davis says that when he was in art school, the big heroes were Picasso and Matisse — "There was a sense, mid-20th century particularly, that an artist's job was to play and keep exploring new subject matter and particularly new techniques." The more recent trend is for artists, especially painters, to specialize in one style and often a single subject. Vadim followed in the footsteps of Picasso, Matisse and their ilk, Davis says.

"He was all about trying different styles. In a way his career mimics the Modernists. He started with the classical training that gave him all the skills and from then on it was about exploring the different approaches," says Davis. "It was more about the journey than getting there."

On Vadim’s website, the artist is quoted saying, "I don't divide my creativity by medium … the materials are just words for my art language."

Gully Clark, curator for the Fine Arts League of the Carolinas Gallery (where a retrospective of Vadim's work is currently on display), points to the effect of Russian literature on Vadim's work. He names writers Pushkin and Dostoyevsky. "What we practice at the Fine Arts League is realism. Realism is taking life exactly what it is without alteration. What the existentialists were addressing was taking human existence in its reality and transforming that into something more noble," Clark says.

"The thing that defines you as a creator is your ability to transform reality," Clark continues. "Even Vadim’s use of color and light is very profound and raises the everyday human experience to something much more mystifying." And, versatility informed all of his art: Vadim’s sculpture and work with form influenced his ability in the two-dimensional aspects of his drawing.

In order to continue working in a variety of mediums, Vadim opened his own gallery so he could show what he wanted, when he wanted, Richards says. And the risk paid off. After the initial cost of getting started in Asheville, he never had to work a second job. And he exhibited the work of other artists as well.

"It used to be that a gallery would represent the artist rather than the work," says Davis. During the 1920s through the '50s, galleries were especially excited to show something different each year by their artists — a fostering of the artist's vision, Davis says. Now, when an artist changes style, "everyone gets very nervous about it. There's a sense of betrayal, almost like [Bob] Dylan going electric."

Vadim fostered his own vision by developing the many facets of his talent; for this characteristic he earned comparision to the Russian-French Jewish Modernist Marc Chagall. His public works include the bronze sculpture "Cat Walk" on Wall Street, a series of sculptures called "On the Mend!" at the Mission Hospital Reuters Center Children's Outpatient Center and architectural embellishment "Nine Grotesques" for local restaurant Modesto. His work is in private and corporate collections, including The Spartanburg Museum of Art, the office of former Senator Bob Dole and the William Jennings Bryan House.

"There were other things he wanted to do, like screen printing and monotyping," Richards says. "I think he could have mastered anything."

Laughter and legacy

Which is not to say that Vadim didn't master the mediums in which he did work. Georgi compares Vadim's drawing to Chinese poetry: "A lot said in a few lines. My dad's drawing, if you look at those classics he has, they're just quick lines that are so expressive," he says.

Such skill stems from the sketchbook-a-week practice which Vadim maintained for more than 20 years, often through making caricatures of those around him. Richard Stiles, a collector, has a number of Vadim's figures, including an out-of-character skinny woman (Vadim favored voluptuousness when it came to the feminine form), three portraits on parking tickets and four drawings of tongues "as tomahawks, the sole of a shoe and coming out of the bottom of a vodka bottle — different things your tongue could do" bought at an April Fools’ Day sale. "I have a picture of him where he's Van Gogh ready to cut off his ear," says Stiles.

That Vadim was equally adept at satirical sketches and sublime landscapes says as much about his disposition as his aptitude.

"It goes back to an Oriental style, finding the most profound meaning in each line,” says Clark. “What he represents in terms of aesthetics is right in line with some of the greatest artists who ever lived."

Collector Jim Kofalt got to experience another side of the artist — Vadim the teacher. "I met Vadim in 2004," he says. "We were introduced by a mutual friend because I had collected bronze sculpture over the years and wanted to learn more." In the course of their conversation, Vadim suggested that Kofalt might want to take a few lessons and see how it felt to sculpt from a student's perspective. "He had a great deal of empathy and understanding for a student's need to develop," Kofalt says.

Kofalt studied with Vadim over the next six years, and also collected the artist's work, including two pieces of sculpture and a number of portraits. Kofalt says his favorite is the painting "Found Earring" because of "the colors he used and blended. It contains both the human form and nature. It's a pleasant and thought-provoking painting."

Clark talks about another thought-provoking piece that used to hang in the Fine Arts League Gallery: a self-portrait in which the artist's eyes are closed. "Often I wanted to ask Vadim, 'Are you foreshadowing your own death?'" Clark says. "In another sense, what he was expressing to me was the artist's ability to change his environment through his imagination, his own vision."

The continuum

Ultimately, does an artist's legacy lie in the hands of fate? Will time will tell what the artist's students, contemporaries, friends and family already knew?

"There's the notion that an artist's job is to paint his experience of life," says Davis. "There is a definite working within the genres — landscape, portrait, the nude. Those are your fixed parameters, but within that, you explore different ways to push those … It would be a good legacy for him to leave for the commercial side of art in Asheville — that art is about experiment."

Richards says that her husband worked in big, universal themes like "The Great Flood," explored serially. His topics could be "almost primordial, the forming of the earth, good and evil" or personal — dreams and scenes from village life in Ossetia. (Russian village scenes were also prominent in Chagall’s paintings.) These series were works in progress with new work continually added. The couple exhibited shows, on occasion, demonstrating the progression of Vadim's work from the spark of the idea in a notebook, through the sketching process, ending with the final sculpture or canvas.

"He always did say, 'There is never enough time for an artist,'" says Richards. "He always felt pressured that in an artist's lifetime, they could never do enough." This proved to be all too true: Vadim was only 56 when he died.

Artists, in a way, are different from other mortals because their work lives on. In Vadim's case, there was still more work that he hoped to complete. An art exchange between Asheville and Vladikavkaz was one such project — though Vadim had moved away, he still considered Russia to be home and was proud of its art. (That project did begin, last year, with a showing of Russian children's art through the Sister Cities program.) Some other large projects, which were delayed while Vadim completed the "Cornelia and Cedric" installation, are left unfinished.

One project was completed, at least as far as Vadim was concerned. He was able to bring Georgi to the U.S. and, in less than a decade, the younger Bora has relocated to New York and is in the process of making his own way as an artist. Georgi says that, as a small child, his father would “encourage me to find answers, to construct ideas to a physical form, to catch them if they were interesting” — these lessons inform his work today.

Vadim left behind other bodies of work that he may not have ever considered for a gallery. For example, Richards says she'd like to do a slideshow of images from Vadim's camera, "how art is seen through the artist's eye." Pictures include cloud formations, elements of nature and still lifes of fruit. "To him, it was already art in nature," says Richards.

Once, while visiting Richards' relatives in Dillingham, N.C., Vadim discovered a large boulder in Big Ivy Creek and insisted on having it pulled up and delivered to the couple's home. "It was a ready-made sculpture," says Richards. That boulder will mark Vadim's grave in the Riverside Cemetery — he lies not far from O. Henry, his favorite American writer.

Appropriately, the grave will also have a bronze bust of Vadim’s called “DNA.” Which, says Richards, "He described as a melding of all his ancestry and himself in one face." An apt finale from an artist who had so much to express.

— Alli Marshall can be reached at amarshall@mountainx.com.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.