There’s a rumor that when author F. Scott Fitzgerald took up residence at the Grove Park Inn, he weaned himself off hard liquor by downing dozens of bottles of beer each day. He also insisted on a room overlooking the main entrance so he could scope out arriving debutantes, and, in a drunken fit, shot a bullet into the ceiling.

Asheville’s had its share of literary luminaries (eccentric and otherwise), from prodigal son Thomas Wolfe to native daughter Wilma Dykeman. The tradition continues, as new waves of writers wash into (and, often, back out of) Western North Carolina.

The constant is that this area continues to foster the written word, serving as a retreat and a source of inspiration. Want proof? June 1 marks the 25th anniversary of Asheville institution Malaprop’s Bookstore/Café. As well as being a place to shop for the broadest spectrum of regional literature, the independent bookseller also serves as a stage for readers and writers of all genres.

But summing up the literary voice of the region can be harder than sharing that first poem at an open-mic night. Southern Lit? Not exactly. Legendary short-story author and Riverside Cemetery resident O. Henry, like contemporary novelist Valerie Ann Leff who lived here for a while, were both raised in Manhattan. “The South has its own literary culture,” Leff said in an interview with Mindy Friddle. “I feel like an oddball.”

In the 1990s, Asheville was defined by spoken-word poetry. There was the Green Door, a gritty little listening room set off Carolina Lane. Writer Allan Wolf was named Slammaster of the 1994 National Poetry Festival, putting Asheville on the literary map. The same year, local poet/rocker Keith Flynn printed the inaugural issue of Asheville Poetry Review (with writing by area scribes Richard Chess, Thomas Rain Crowe, Ann Dunn, Katherine Graham, and David Hopes), which would go on to become an internationally distributed publication.

But by the new millennium, poetry slams had trickled down to a whisper and a new literary scene was gaining voice: that of the author backed by a major publisher. While a novelist distributed by, say, Random House is a far cry from Asheville’s DIY sensibilities, even the most idealistic artists need to make a living. In the case of Cold Mountain author Charles Frazier’s recent $8-million advance for Thirteen Moons, it can be a very tidy living. (Frazier was born in Asheville, and his two blockbuster novels are both set in the surrounding mountains.)

This posher, slicker model—in keeping with a posher, slicker skyline and a steady influx of posher, slicker residents—may well herald a new direction of the local literary scene. But is there still room for an emphatic poet or two, peddling hand-made zines?

If you write it, they will come

“I wondered if some of what we’re seeing now in terms of more well-known writers coming into the area is the end result a long process,” suggests novelist and Great Smokies Writing Executive Director Tommy Hays. He points first to O. Henry Prize winner and Western Carolina University professor Ron Rash, “who worked hard for many, many years before he started publishing novels like crazy.” Another friend, George Singleton from Greenville S.C., “wrote hundreds of stories and published in small magazines for many, many years before he had his first book. Now it’s like a book a year or so.

“So maybe,” suggests Hays, “some of what we’re seeing around here is the result of something that has been in the works for at least a decade.”

And maybe, “as these writers succeed, other writers hear about Asheville and think, ‘Well, that would be a cool place to write.’ I wonder how many writers moved here because of Cold Mountain? I bet a bunch.”

Keith Flynn also refers to the spiritual (if not financial) benefits of the area, and local poet Graham Hackett asserts that what Asheville lacks in publishing resources and industry, it makes up for in networking opportunities.

That theory doesn’t apply just to writers toiling solo over manuscripts. It’s the virtual cattle call of the literary conference. Despite the reputed reclusive nature of writers, conferences and workshops have long been part of the writing tradition. On June 2, former N.C. Poet Laureate Fred Chappell, a native of Canton, will be the keynote speaker at the North Carolina Writers’ Network’s Spring Conference. July 13 through 15, the Appalachian Writers Association holds its annual conference in Kings Mountain, Tenn.

And while these events’ high prices might alienate those on student salaries, many writers nonetheless find a way to ante up the cash. However, the $429-per-night price tag on the Southern Living-sponsored Writers’ Winter Weekend held at the Inn on Biltmore this past March was not for the faint-of-pen. And yet someone is supporting the high-end happening: Blogger joyfuljotting-janet, for instance, crowned it “one of the most enjoyable weekend events” she knew about—and 2007 marked the Writers’ Winter Weekend’s sixth year.

Sonic youth

“[These events] are almost contrived to drive out the youth movement,” declares Audrey Hope Rinehart, an event coordinator with Flood Fine Arts Center in the River District. “The only people who can afford them are retiree white people … who tend to work in certain genres” (e.g.: mystery or romance).

Her answers include a Flood Center reading series and, soon, affordable workshops from which organizers will cull a quarterly journal.

The readings, a continuation of an event begun by former Asheville poet Jaye Bartell, focus on craft rather than on performance.

“What has been featured in Asheville for the past 10 years was slam work,” Rinehart confirms. “That’s very different from craft work.”

Interestingly, she says it was a “strong dynamic among some younger people to cultivate this particular change.”

But, while Rinehart and her colleagues are pushing for poetry as a written art rather than as a spoken medium, they’re not necessarily proponents of university programs. Rinehart has a bachelor’s degree in writing, but felt unsupported in an academic environment. “The more a writer avoids university programs and reads a lot and crafts their work on their own … that’s where the revolutionary work comes from,” she insists. “We need to reach into the canon, take what we learned there, and take it back to the grassroots.”

Speaking of university programs, Warren Wilson College’s prestigious, low-residency MFA in Writing program costs about $6,775 per semester, or $27,500 to complete the two-year degree—a sizable sum that can make the do-it-yourself approach that much more appealing. (By comparison, UNC-Greensboro’s on-campus program runs $1,346 per semester for state residents.)

“We also need small presses, not related to a university,” suggests Rinehart, though she doesn’t consider Asheville Poetry Review a viable option for up-and-coming writers. “They like a certain type of work. As they are right now, they’re not reaching into the community to find new talent,” she says of the local institution.

“If a poet’s getting published by nobody and then they don’t get published by the Asheville Poetry Review, they don’t scream and yell that poetry magazines suck—they scream and yell that Asheville Poetry Review is not representing them,” counters Review founder Flynn. “The thing has grown from absolute-nothing beginnings to an international journal.”

But even so, he doesn’t consider the Review elitist. “Even last issue, [which featured] some of the most famous poets in America, scattered throughout there were 10 or 12 Western North Carolina writers.”

Flynn insists that despite the 8,000 submissions he receives for each issue, he still gives local and statewide writers special consideration. “I have to submit my [own] poems to editors, just like everybody else,” he points out. “I want my editing to bear the quality of tenderness.”

Paradise found

Flynn, raised in Marshall and long an integral figure in the local poetry scene, claims he recognized a movement starting in the late 1980s and early ‘90s, which compelled him to start Asheville Poetry Review “to document a literary renaissance that was taking place in Western North Carolina.”

He bears witness—“the best [regional writers] now have national reputations”—by naming local poets Crowe, Hopes, Chappell and Michael McFee, plus current N.C. Poet Laureate Kathryn Stripling Byer, of Cullowhee, and novelists Ron Rash and Clyde Edgerton. (Flynn’s own published works include four books, most recently poetry collection The Golden Ratio and essay collection Rhythm Method, Razzmatazz, and Memory.)

No one on that list is known for prowess at poetry slams.

“Slam poetry, as a movement, flamed out,” Flynn asserts. “What happened here is [that] the best of the poets, not necessarily the slammers, continued to thrive and to work. As a consequence, the slam movement died out. That happened everywhere; it wasn’t just local.”

“Slammaster” Allan Wolf, while still alive and well in Asheville, has parlayed his innate sense of verse and performance into children’s and young-adult books. He’s also an educator and a presenter; his continuing mission (as stated on his Web site, allanwolf.com) is “to take poetry to the people.”

Stepping into Wolf’s place at the mic is relative newcomer Graham Hackett. The presence behind Poetix Lounge—a bimonthly thematic poetry event—sees slam and spoken-word poetry as absolutely current.

“The Lake Eden Arts Festival slam is very valuable,” he notes. “It’s attracting poets from as far as Chicago, and a regional effort is one of the components to getting this area recognized again.”

Hackett points to WordFest, an event he’s co-organizing for next year that will feature renowned poets Galway Kinnell and Patricia Smith, as evidence that spoken word still has a local voice. “There’s a resurgence right now,” Hackett insists. “The very public intention of the [Asheville Area] Arts Council to bring spoken word to schools means there’s a youth movement, but it’s also done with the support of [people formerly associated with] the Green Door. They’re supporting Poetix Lounge.”

Name dropping the Green Door, even most of a decade since its demise, gives you instant local-lit cred. Enough for Hackett to surmise that the current literary climate, the blending of old guard and new, is “a perfect storm.”

But he already has his sights set beyond the mic. Sharing the “poetry to the people” ideology with Wolf, he created Catalyst Productions, an umbrella organization which includes Poetix, a social-activism program reaching out to at-risk youth.

Funded partly by grant money, Poetix first worked with students confined at the Swannanoa Youth Development Center, teaching them to channel anger and angst into written and spoken poetry. Their compiled works can be found in the collection Voices From Inside.

If the teaching-poetry-behind-bars model sounds reminiscent of the 1998 film Slam, there’s good reason: Hackett calls the movie—tagged “Words make sense of a world that won’t”—an inspiration.

Therapeutic program Horse Sense of the Carolinas, based in Marshall, “picked up the Poetix pilot program as part of the local initiative The Buncombe County Gang Violence Prevention Program,” reveals Hackett. “They brought me in to work in conjunction with their psychotherapy … it’s mind-blowing more than it is frightening. The atmosphere is very conducive to helping [gang kids] open up and promote their healing.” Poems from that program are compiled into the chapbook The Mane Lines.

Writers giving back generally remains a local theme: not surprising, since writers have long earned their livings as teachers. Novelist Hays jokes that his literary agent couldn’t buy lunch with the percentage she earns from his books. It’s an exaggeration, but luckily for the local community, Hays’ other job is at UNCA.

In his Great Smokies Writers Program, “what we do is work with people in the community who are writing,” Hays says. “The classes that almost always fill are the fiction and prose classes.” He points out that many would-be writers who relocate to the area are at an age when their children are grown; they’re retired, and they suddenly have time to pursue a novel or memoir.

“There’s not a week that goes by that I don’t talk to someone who’s writing a novel.”

A far cry from black tie

GSWP works with writers of all levels, from those just beginning to those considering publication. However, while how-to classes abound here, the publishing industry is still a blank page.

Hays sensibly points out that a literary agent in our mountain town is too far from the New York-based industry giants. A few Asheville-based small presses release a handful of titles each year: Flynn has Animal South Press; Malaprop’s owner Emöke B’Racz started Burning Bush Press; Rain Crowe founded New Native Press in Cullowhee; Sebastian Matthews puts out literary journal Rivendell; A-B Tech publishes the college’s literary journal, Victoria Press; and there’s Front Street Books, an award-winning national publisher of books for kids, located in West Asheville. The area’s largest publisher, Lark Books, releases enticingly packaged coffee-table tomes on crafts, food and decor—but, disappointingly, nothing in the literary vein.

However, this is the land of the sky (read: dreams). A larger, independent press is a possibility: Flynn admits that every time he and B’Racz get together, the subject arises. And new writers with new ideas, new energy—maybe even new money to fund such programs—keep steadily moving in.

UNCA and Warren Wilson continue to gain notoriety and bring established authors into the area, and perseverant writers make names for themselves on the national front. Asheville is a town intricately, if complicatedly, linked with writing.

It’s just that its literary rep can’t be neatly shelved.

“I don’t even know what the Southern Lit genre is anymore,” sighs Hays. “We’re a great mix, and that makes us healthy.

“I don’t think Asheville’s become any more dressed up than it ever was,” he says, adding, “I certainly hope not.”

• Malaprop’s (55 Haywood St.) celebrates its 25th anniversary with a champagne toast and 25-percent-off sale storewide on Friday, June 1, 7 p.m. Info at 254-6734.

• The Flood Gallery Reading Series is held next on Friday, June 15, 8 p.m. Free. Info at 712-3953 or 776-8438.

• Graham Hackett hosts youth-poetry series OrganizedRHYME at Malaprop’s on Tuesday, June 26. 254-6734.

• For information on the Great Smokies Writing Program’s fall classes, contact Tommy Hays at 254-1389.

• Learn about the Asheville Poetry Review at ashevillereview.com.

Local writers in print

Most readers are aware of the literary contributions by Asheville-area natives and visitors such as Thomas Wolfe, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Zelda Fitzgerald, O. Henry, Carl Sandburg, and Black Mountain College poets Charles Olson, Robert Duncan, Denise Levertov, Jonathan Williams, Ed Dorn and Robert Creeley. But WNC’s best writing is hardly in the past. Contemporary wordsmiths (some natives, some residents, some having moved on to other locales) are still doing this corner of the world proud. The list includes:

• Charles Frazier, raised in Asheville. His first novel Cold Mountain (1997) was made into a major motion picture. His second, Thirteen Moons, earned him a reported $8-million advance.

• Gail Godwin, born in Asheville. Godwin is a visual artist, composer and award-winning writer of nonfiction, essays, short stories and book-length fiction. Her most recent novel is Queen of the Underworld (2007).

• David Brendan Hopes, UNCA professor. Hopes is a visual artist, actor, playwright, poet and Pulitzer Prize nominee. His most recent collection is Birdsongs of the Mesozoic (2005).

• Valerie Ann Leff, former resident of Asheville. Once associated with the Great Smokies Writing Program, Leff recently had her first novel, Better Homes and Husbands (2004), optioned for a TV series—NBC’s answer to ABC’s Desperate Housewives.

• Marisha Pessl, attended high school in Asheville. Pessl used the experience as the setting for her smash debut novel, the critically drooled-over Special Topics in Calamity Physics (2006).

• Ron Rash, Professor in Appalachian Cultural Studies at Western Carolina University. Rash is the author of poetry and short-story collections, one children’s book and novels (most recently The World Made Straight, 2006). His short-fiction piece “Speckled Trout” was anthologized in the 2005 edition of the coveted O. Henry Prize Stories series.

• Selah Saterstrom, former Asheville resident. Now based in Colorado, Saterstrom parlayed her Southern Gothic sensibilities into a collection of prose poems she refers to as parables. Her book, The Meat & Spirit Plan, will be released this fall.

Open-door policy

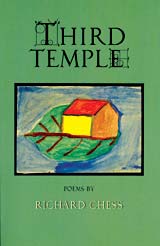

Poet Richard Chess, in his day job, directs the Center for Jewish Studies at UNCA. And while Third Temple (University of Tampa Press, 2007), his third book of poetry, is hardly a textbook-dry primer for impressionable students, Chess does allow his professorial voice to come through from the outset—but perhaps most noticeably in the collection’s final poems, which explore the intricacies of the Hebrew alphabet. Even in his most personal poems of love, grief, spiritual grappling, sexuality and death, Chess asserts his role as an usher of sorts, guiding the uninitiated into the language and multilayered textures of the Torah.

Can a non-Jew truly relate to Temple? Hard to say. But the openness of the book, the spaciousness and light quality of poetry, allows a reader some access. Temple is one man’s journey to understanding his own religion and culture, but it’s also an invitation to the greater world.

The book opens with a seemingly lighthearted poem about Chess’ faithful brown Lab. There’s a Mark Strand quality to the writing, a frivolity belying a deeper, darker truth: the unconditionally loving canine as both metaphor for our supposed obedience to God and juxtaposition against a cruel deity.

But it’s the happy-go-lucky dog that wins the reader.

Temple uses the exclusive syntax of Jewish prayers. But charmingly self-effacing lines like “if I weren’t a Jew I could be / comic without being tragic,” and the jazzy poem “Rabbi Gets Around,” make Temple a fast-paced read. As is likely true of Chess’ teaching style, the book is friendly, up-front, and real. And on-par with America’s best contemporary poets.

Rick Chess shares excerpts from Third Temple as part of a poetry-reading event, “Poetrio,” at Malaprop’s on Sunday, June 3. The 3 p.m. event also features Kate Northrup and Ann Campanella. Free. 254-6734.

It would be nice to see more recognition for these great authors! They could consider Youtube booktrailers?? Book trailers are a great way to encourage people to read! And an easy way to judge a book by more than just its cover! You can see some book trailers right on YouTube! http://www.youtube.com/booktrailers