Look at Tim Barnwell's photograph: an unassuming woman, standing on a dirt road, near a cornfield. One might be surprised to discover that this woman is the legendary ballad singer, Dellie Norton, famous for her a capella English and Scotch-Irish murder ballads and love songs. When Barnwell took her photo in 1980, she was over 80 years old. In a threadbare dress, apron, and slippers, she stands on her piece of land in Madison County, where she was born and lived until she died in 1993.

Through October 2010, visitors to the Asheville Art Museum can see the original silver gelatin print of Norton along with 33 other images, culled from the 85 portraits in Hands in Harmony" Traditional Crafts and Music of Appalachia (W.W. Norton 2009), Barnwell's latest book of Appalachian photographs

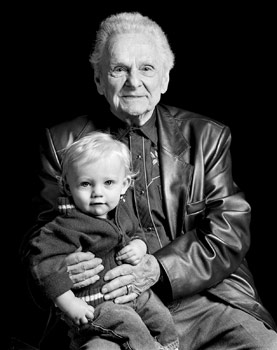

Spanning almost three decades of Barnwell's career, Hands in Harmony is a testament to a generation of Appalachian folk that is gradually passing on. The photographs document a people who learned their songs and crafts through an oral tradition; a culture whose need for tools and utilitarian objects spurred the development of today's crafting industries. Most of the people in Barnwell's book were photographed when in their mid 60s and nearly a fourth of them have passed away since he took their picture.

Frank Thomson, curator for the Asheville Art Museum, had the difficult job of deciding which photographs to include in the museum's exhibit. Working with Barnwell, he arrived at 34 images – half of them musicians, half of them artisans. Among them are some rather renowned people, such as Ralph Stanley Jr., Doc Watson and Bill Monroe. "We didn't just want to pick famous people," says Thomson, "we wanted a nice variety of arresting images that reflect what's in the book."

Before he produced the portraits, Barnwell spent hours getting to know each person first. Using a hand-held recorder, he taped conversations before preparing his camera. Often he returned for a second and third visit to get more stories and more photographs. "I think I was tapping into this idea of visiting with your neighbor, which is a thing of the South," he says.

Excerpted transcripts of Barnwell's conversations can be found next to each photograph in the exhibit. The text panels show the colorful and cadenced Appalachian dialect. "I dream a lot of chords and put them together," reads the text for blues guitarist/singer Etta Baker, "When I hear music I don't sleep sound, just enough to dream on."

Barnwell shot some of his earlier black and white photographs with a 4"x5" large-format camera. Usually set on a tripod, the accordion-bodied 4"x5" camera is traditionally used for static subjects, such as landscapes and architecture. The film is loaded for each shot, and the aperture setting manually adjusted every time the light shifts. The resulting image looks as antiquated as the camera itself. Later, Barnwell switched to a 2 ¼" view camera, which is more versatile as the settings don't require such frequent adjustment.

Without the veneer of color, Barnwell's photographs emphasize graphic elements that give visual and conceptual vividness to his work. The dried and cracked clay covering the apron and studio walls of potter Walter Cornelison, for example, contrast his slick, wet hands and the smooth, newly-thrown vessels that line his table. These compelling textures allude to cycles of birth and death and the passage of time.

"Black and white is the medium of history and memory," says Barnwell. "It's also an abstraction of reality. It's taking things and moving them into a different realm. We're forced to confront them a little bit."

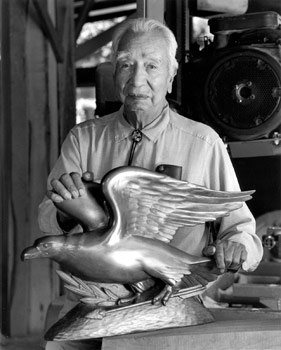

Some of the portraits are formal in their presentation, such as the

photograph of Going Back Chiltosky, a Cherokee woodcarver, who gazes serenely at the camera, hands resting on his carving of an eagle. Other portraits capture the person at work within his or her surroundings, like the picture of Ralph Gates, maker of broom handles, who carves patiently in his shop and is surrounded by coarse piles of wood.

"Something to do with their hands"

Born in Jackson County and raised in Asheville, Barnwell has been practicing the craft of photography since the mid 1970s, when he was a political science major at UNCA. The school didn't have a dark room, but Barnwell's adviser encouraged him to produce photographs anyway, and they appeared in some the school's publications. Soon after graduating, he attended a workshop in Maine to learn The Zone System, a set of techniques developed by landscape photographer Ansel Adams to minimize the discrepancy between what the photographer saw through the viewfinder, and the final, printed image.

In 1980, Barnwell opened the Appalachian Photo Workshops program in Asheville while working as a commercial photographer throughout Western North Carolina. During his free time he visited rural communities to meet people and shoot photos. "I would take a day off — usually Mondays because we didn't have any workshops on that day — and go out and drive around," he says. Soon his photojournalist works were published in local as well as national publications, such as Newsweek and Time.

"I love traveling to other regions to take photographs, but I don't think you can do justice to areas you're not familiar with," says Barnwell. The shifting light on a field, or a region's weather patterns and seasonal changes are some important elements to be aware of as a photographer, as is cultural familiarity, he explains. "If you're gonna deal with people, you have to have a connection to their way of life."

For more than three decades, Barnwell has documented Appalachian culture. His books The Face of Appalachia: Portraits from the Mountain Farm (2003) and On Earth's Furrowed Brow: The Appalachian Farm in Photographs (2007) capture the family-farm lifestyle of mountain communities during the 1980s, when tobacco fields and mule-driven plows were a part of the everyday landscape. "Today, the younger generations can't afford the rising taxes on the land so they can't afford to keep it," says Barnwell, "It used to be that the commodities were grown on the land, but now the land has become the commodity."

Curator Thomson credits Barnwell's evocative photography to his vast knowledge and experience with the area. "He's spent decades in this region, and has seen how it's evolved from farms leaving to crafting businesses taking over."

It makes sense that the third book in Barnwell's Appalachia series documents artisans and musicians. To find subjects, Barnwell approached the Southern Highlands Craft Guild, who put him in touch with some of their heritage crafters. Through the Guild, he met basket weaver Nancy Conseen, who later introduced him to Cherokee artisans. "She gave me instant credibility," he says.

Local musician Don Pedi played a large part in introducing Barnwell to players in the Appalachian old-time and blue-grass music scene — music that Barnwell has come to appreciate deeply. "Some of these songs have come from Scotch-Irish ballads of the 1600s, and have stood the test of time," he says. "There's a real authenticity to that type of music." Often, Pedi accompanied Barnwell on his visits, playing his dulcimer with the subjects while Barnwell readied for the shoot.

During photography sessions, Barnwell observed the ways his subjects sat, their gestures and facial expressions, and mentally drafted the composition. "When the camera comes out people have a tendency to present themselves — get into pose, sit upright, smile for the camera because they think that's what I want."

It's not just a likeness that Barnwell is going for in his photography. He wants to capture the subject fully immersed in his or her environment. "I try to get them involved as a participant rather than a subject," he says. "Some people are really shy. I find that if you can just give them something to do with their hands, that engages their brain, and they relax. "

Barnwell is frequently asked why he doesn't turn to the more comprehensive video documentation, to capture the images and sounds simultaneously, as well as movement and the progression of time. "There's just something about the still image that video cannot capture," he answers. "With the single image you can create something that can be studied. It's one moment frozen in time."

Curiosity is the most important motivator for his photography, Barnwell says. "Doing all of this is an excuse to meet people, to get to know them and see how they live. It's all been a learning process for me."

[Ursula Gullow writes about art for Mountain Xpress and her blog, artseenasheville.blogspot.com.]

who: Tim Barnwell

what: Hands in Harmony: Traditional Crafts and Music in Appalachia

where: Asheville Art Museum's Holden Community Gallery

when: Through October 10. A special event will be held at Diana Wortham Theatre in September, featuring musicians documented in the show. Details to be announced.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.