Asheville receives no shortage of media and artistic attention for our cultural oddities, art and fashion. But in A Documentary of Sorts, a new photo exhibition opening Friday, Aug. 2, at Izzy’s Coffee Den, distances itself from this type of portrayal. Asheville photographer Anthony Bellemare has instead looked to the peripheries of Asheville’s cultural stratosphere for subjects.

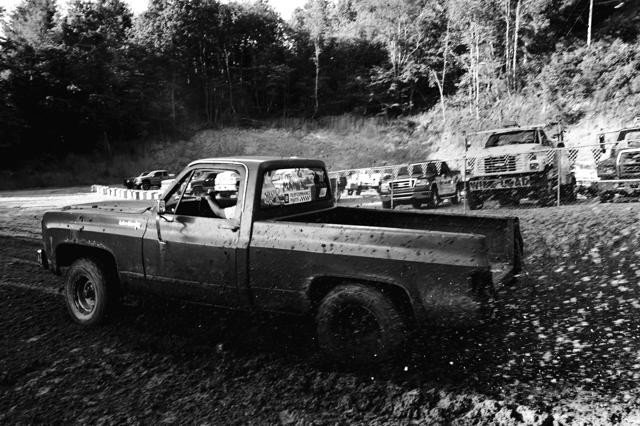

Thirty-eight black and white photographs hang from several cables anchored into the walls. Each work explores and records one of four regional scenes: falconry, kayakers at the Green River Race, the Big Dawg Mud Sling in Burnsville and street-shot portraits.

The works, he says, are subdivided into mini-photo documentaries — each being a study of one particular event, moment or group of individuals living and working in the area.

Falconry, by the way, is the practice of hunting small game with specially trained birds of prey, and it’s been around for thousands of years. Bellemare spent several weeks in early winter of 2012 going out with Asheville area falconers, photographing the process, techniques and the people and collecting information about the practice.

He did the same for the Green River Race and at the Burnsville track, but on a grander scale. Those two bodies of work are years in the making. Each is built from repeated trips to Burnsville and the Saluda area. As with the falconry, the more he learned about each event and person, the more telling the photographs.

“It’s trying to get the experience from the larger sense of place, a sense of the people and the details,” Bellemare told Xpress. “It’s the feeling of movement and sound, but without hearing it or seeing it.”

The portraits, though few in number, have been culled from a larger body of work taken from everyday downtown life. They offer pared-down views of individuals in Asheville, but they don’t necessarily convey Asheville. That’s to say, the works avoid territorial and cultural recognition of our patented everyday oddities.

Bellemare’s work offers a reprieve from such photography. You won’t find any trace of downtown’s socio-cultural bubble, which can be, at times, underwhelming — particularly when spelled out in repetitious ‘8-by-’10s (even more so after a major festival weekend). With the exception of the few portraits, he’s almost entirely departed to the countryside and the woods.

He began going to the race track three years ago. The track itself is a straight, mud-filled pit lined with concrete blocks that drivers bolt through, slinging mud everywhere, including the audience. Bellemare’s first few visits were as a general spectator, but he soon began meeting the drivers and families involved. Photos take in action shots of the cars and trucks roaring through the mud. Others feature crash scenes, families in the audience and pre- and post-race get-togethers.

“I’ll change what the focus of the character is,” he says. “It’s so that I see it differently.” Those characters are the vehicles, the crowd shots and then the people involved. Those who manage to hold still long enough for a portrait do so with comfort and unabashed pride.

It’s in pursuit of timelessness, according to Bellemare. Any one of his photographs could’ve been taken within the last 30 years and in any number of places — a factor he largely attributes to the black and white medium. But it’s his alternating focus between individuals and objects, still shots and motion that simultaneously separate the viewer from an official time stamp.

The trucks are old, but not old enough to qualify as vintage. And rivers don’t show too many signs of short-term aging, though, kayakers could probably judge by the boat models. The people he’s photographed have been meticulously captured to deny an exact sense of time. They, too, are devoid of the technological cues that could cement them into the past or present.

“It gets it to a basic level,” he says. Each series is about a particular event, leaving each photo to be a particular instant of that event. “It’s a moment in time, rather than a date and time.”

When viewed separately, his subjects could have been plucked from any city street, river, racetrack or countryside field. But they’re regionally relevant when drawn together.

The four groups end up exemplifying a different view of WNC. It’s a view that’s arguably been around for decades. But it ignores the eccentricities that have come to define downtown Asheville. It’s a view that bypasses the waterfalls, creeks and Blue Ridge Parkway overlooks and goes straight to a unadulterated population that lives and breathes without regular, anxious attention from tourists and cameras alike.

A Documentary of Sorts opens Friday, Aug. 2 from 7 to 9 p.m. at Izzy’s on Lexington Avenue.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.