Color me impressed: “Hot Ass Baby,” 2000, by Sherri Wood; embroidery and mixed-media on found doll. Tattoo design by Denise de la Cerda.

|

If you have an all-consuming obsession to learn all there is to know about tattoos, Asheville Art Museum is the unlikely repository of a good deal of information. Under the Skin: Tattoos and Contemporary Culture is an exhibit in the big upstairs gallery filled with historic and anthropological materials about the topic, contemporary art that details current activity in the field, and a side project that exposes the tats of highly decorated locals.

But mostly there are walls of flash — the preliminary drawings made by artists before applying the images to skin — as well as various tools of the trade.

Local human canvases: (from left) Chad McRorie, Kristin Welch, Christine Whittington and Marc Kane. (From the auxiliary exhibit Under the Skin of Asheville: A Portrait Project, at Asheville Art Museum.) courtesy Paul Jeremias Photography

|

When a member of the museum’s inner circle was asked about attendance for the tattoo show, she rolled her eyes and quipped, “The only ones coming to see it are those who have them.” But curator Ron Platt is gratified that the show has attracted an audience new to the museum; he claims that many of the “regulars” are enjoying the work, too.

“One long-time member remarked, ‘I would never get a tattoo. I hate them — but I like the exhibition,'” Platt reports.

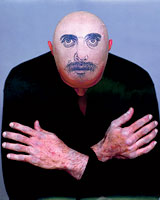

“Alex on Alex.” Tattoo by Kandi Everett, 1982. Photo by Shuzo Uemoto.

|

The curator says the idea for the show came from his looking around and realizing how integral the tattoo artist is to Asheville’s culture. “After the ’60s and the ’70s, the ideas about what art is have broken down,” Platt points out. There’s no question about the artistic skill seen demonstrated on the bodies of many on Asheville’s streets. Producing the flash for the tattoos takes a great deal of technical ability, and reproducing these drawings on living flesh a great deal more.

According to a local tattoo artist, at least half of her peers working in Buncombe County have been to art school. Others have learned their trade as apprentices.

The exhibit opens with old engravings, photos and artifacts from around the world describing the many societal implications of tattoos and scarification, including full-body tattoos in Japan and those made with a chisel on the faces of the disenfranchised Maori. A powerful African vessel representing the female as mother is outstanding: Raised marks in the clay symbolize those placed on the body of a woman after she has given birth.

Interest in the topic by mainstream contemporary artists is seen in Sherri Wood’s dolls, who wear their doll-flesh-colored body suits embellished with elaborate embroidered designs cascading around their innocent-looking torsos. Painter Thomas Woodruff shows ornately framed paintings of tattoo motifs done in the style of the Dutch masters. Nan Golden’s photo of a tattoo in progress is, as you might expect, somewhat disturbing. There is a depressing video documentary about abused Russian prisoners and what their prison tattoos mean to them.

The exhibit’s real meat, however, is in the flash, not the flesh. Hung almost salon style, floor to ceiling, the drawings are displayed as they might be in the tattoo parlor. A few pieces are old and unattributed, but most bear the artist’s name, and some include information about their careers.

A number of images are part of almost every artist’s repertoire: eagles, snakes, skulls, fish, and tigers. Others are more unique. Jill Jordan presents a female scuba diver surrounded by ocean vegetation. Surprisingly, though, her image of the female form mimics those much-older examples seen in work by male artists: a pin-up-worthy body featuring tight, round buns and perky breasts with prominent nipples.

Conversely, a photo by Pat Fish shows tattoos of flowers camouflaging a double mastectomy. Kandi Everett’s portrait, tattooed atop the head of her sitter, makes you take another look. And Spider Webb’s chess set, made from tattoo machines and pieces of melted metal from the World Trade Center, moves into the conceptual realm.

Joseph Ari Aloi’s bluebird and his “Madonna and Child” are relatively benign, while Greg Irons’ grim reapers are somewhat terrifying. Some of the scariest images come from Dana Brunson and Scott Harrison. Brunson’s work depicts a woman with bat wings and a snake coiled around her turbaned head, plus another serpent around her neck. Harrison’s rat lies on his back doing something your mother told you would make you go blind.

Nick Bubash also takes an irreverent approach, showing praying hands with the index finger missing and the text “Forgive Me, Mother.” He also offers a Jesus head with a blank space where the face should be: “Your Face Here,” it prompts. Leo Zulueta, on the other hand, is careful to show respect for the tribal traditions he emulates. His forms are based on those of Polynesian cultures, though he never duplicates one exactly.

This show may divulge to the average viewer more than he or she ever wanted to know about tattoos. It may or may not change some viewers’ perception of tattooing as a low-brow art. Its one sure effect will be the perpetuation of the genre: Younger attendees will likely be making plans for their first (or next) visit to their local tattoo emporium.

[Connie Bostic is an Asheville-based painter and writer whose work can be seen in the Small Works Invitational at Blue Mountain Gallery in New York.]

Under the Skin: Tattoos and Contemporary Culture and Under the Skin of Asheville: A Portrait Project show at Asheville Art Museum (2 S. Pack Square) through Sunday, Oct. 29. Auxiliary events include: “Open Mic: Tattoo Tales” (Friday, Aug. 25, 6-8 p.m.) and “Talking About Tattoos: Memoir, Oral History, and the Marked Body,” with author Christine Whittington (Friday, Sept. 8, 6-8 p.m.). 253-3227.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.