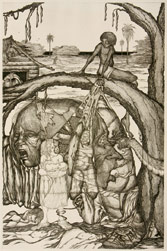

Master printmaker Kore Loy Wildrekinde-McWhirter’s latest work, redhanded: a songe forre the loste, was seven years in the making and debuts this month at Warren Wilson’s Holden Gallery. The series addresses what the artist calls “the longest undeclared war in history,” a war of violence committed against children.

Wildrekinde-McWhirter spent her formative years in a fabricated, closed, 14th-century European society in the jungle islands of Paraguay. “In an attempt to replicate the early Christians, this group associated itself with sects of the Mennonites, Amish and Hutterians,” she says. Decades later, these experiences and the ongoing violence she observes in today’s society deeply inform her work as a printmaker.

redhanded: a songe forre the loste comprises 13 line etchings (12 inches by 18 inches) accompanied by 13 letterpressed poems and 17 letterpressed pages of text (also 12 inches by 18 inches). Of these, 23 are completed as boxed portfolio editions that include a forward, a one-of-a-kind opus explicating Wildrekinde-McWhirter’s inspiration for the series.

The artist founded hellbendre presse in 2000. She has drawn all her life and been a printmaker for 11 years. Her work has been shown in selected group, juried, and solo exhibitions, including the Women’s International Print Portfolios.

The following is an excerpt from a longer interview conducted in the artist’s studio near the South Toe River:

Xpress: Can you describe the kind of violence this series addresses?

Kore Loy Wildrekinde-McWhirter: Living in mortal terror as a child sensitized me to the loneliness and terror that many children are subjected to. The whole series really speaks to the untold stories of everyday violence. Some prints speak of it more iconically, like “carrionne crone,” “unwholye trinitye/intimate predator,” and “beatinge the deadde horse withe the familye jewelles.” Some are more literal and describe specific rituals that other children in the group and I went through.

Can you say more about the physical process of making these prints and why you chose etching, specifically?

The thing I love about drawing and printmaking is that it uses all of the senses. When I’m etching on the plate, I try to listen for and include everything possible. If I make what might be construed as a mistake, dropping the etching tool on the plate and making a big scratch, I draw the scratch into the image. What that does is opens me up, shifting my opinionated self so I have to look at it in a different way. With the intaglio process, there’s something about the acid etching that is very meaningful to me because it’s tearing away the metal and replacing what was taken away with the ink. With printmaking, I can draw the matrix and print 43 of them instead of having just one. This makes the work more accessible to all of us instead of just one person. It’s putting information into the hands of the random many instead of the chosen few.

Do you consider yourself a survivor?

I don’t consider myself a survivor with a capital S. I call my modus operandi “applied belligerence.” With applied belligerence, I have gained compassion, understanding and resilience. The experiences I had strengthened my sense of the ridiculous.

Say more about that sense of the ridiculous. What purpose does that serve?

To me, there’s an extreme sense of the ridiculousness of humanity and satire in these prints. For example, in “gravitye/levitye” there’s a goose turning into a sheep in the middle of the drawing. That’s my mother and it’s sort of a joke about this certain way that many women have of feigning foolishness when they’re actually very intelligent.

Can you describe some of the repeated images in your work and what they mean?

In several of the prints, there will be a woman or some women that have polka-dotted clothing or kopftuchs (head cloths). That was the cloth that the women in the group that I grew up in wore … The fish hold two meanings for me. It’s the cold fish that operates automatically. It doesn’t have any heart or soul or sense of morality and it runs in a school. The fish are also the sect’s programming.

What is the significance of the number 13?

When I came out of the group, I started reading everything I could lay my hands on because general knowledge was verboten in the group. I found that in the institutional forms of religions, the number 13 is often considered an evil number. Well, in the early forms, the number 13 was a form of natural magic. I like that and I like prime numbers, the number 13 particularly, because once you get to 13, there’s almost too many to count in a snap judgment. There’s some safety in that number because it can’t be counted quickly and it can’t be divided against itself.

[Katey Schultz writes from Bakersville and can be reached via http://katey.schultz.googlepages.com. ]

who: Kore Loy Wildrekinde-McWhirter, printmaker

what: redhanded: a songe forre the loste

where: Holden Gallery, Warren Wilson College

when: Reception on Friday, Oct. 10 at 6:30 p.m., with gallery talk by the artist at 7:30 p.m. (exhibit runs through Nov. 7. 771-3034)

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.