Not popped-and-locked into one genre: Some breakdancing diehards object to the form being choreographed with other kinds of dance (or choreographed at all, for that matter). But Rennie Harris Puremovement has another story to tell.

|

Audiences — the type that shell out for ballet or modern dance — have been intimidated by hip-hop, explains Brandon Albright. “They think, ‘Aw, we don’t want to see that booty-shaking,’ or ‘That music is too hard and has cursing.'”

As the assistant artistic director for Rennie Harris Puremovement, a hip-hop troupe that stretches street moves to high art, Albright knows that such closed-minded theatergoers are dancing in the dark.

“They don’t know what they’re getting — and a lot of times, they’re blown away by what they see.”

After a generation’s worth of Fly Girls, moonwalkers and suburb-ified moves tossed into videos by the insubstantial likes of Christina Aguilera and Justin Timberlake, hip-hop dance has irrevocably accessed mainstream consciousness. So exactly what whammy does Puremovement pack when it comes to their stage version of the genre?

Reaching deep

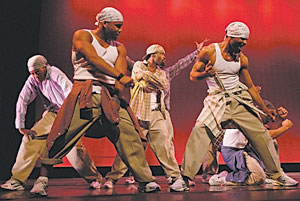

Philadelphia-based choreographer Rennie Harris starts off his repertory on a light note: A crew of baggy pants-wearing B-boys drop into acrobatic floor work with rubbery-limbed fluidity. Headspins, buttspins and gravity-defying freezes prevail as dancers one-up each other with increasingly difficult moves. “Continuum” has a party feel to it, with humor oozing from complex moves set to beat-heavy jazz.

But it’s not just street culture shined up for stages usually frequented by ballerinas and “real” modern dancers. Harris’ material boldly moves into themes of family dysfunction, poverty and violence. According to Albright, the dance tells the story.

“When you see people dance [on the street], they’re really doing the same thing in their way,” he allows. “For them, it might be about a celebration — something to trigger the good side of themselves.”

But he points out that trick-heavy street performances are more about wowing passersby to toss dollars in a collection bucket.

Harris, on the other hand, wasn’t expecting any money. The choreographer started entertaining with a group of dancers at local community centers. “Rennie said somebody actually commissioned him to do three pieces for $1500,” Albright recalls. “He was like, ‘Huh? They’re gonna pay me for something I love to do?'”

As for Harris’ dancers, it’s no longer a matter of reeling in spare change — but members do have to win over theatergoing audiences, who fork out $30 a ticket.

Forget the gymnastics — here’s the big departure from the usual dance fare: “In a lot of modern or ballet shows, they don’t have too many dark pieces, or anything really telling about what’s going on within them,” Albright explains. “We come from deep down.”

Reintroducing the worm

During the edgy, red light-and-voiceover piece “Endangered Species,” Harris moves through his own tribulations, including the time he witnessed his brothers attack his sister when she came out as gay. The last words of the emotive number are: “I learned there are two things I can do in this world: Stay black and die.”

With this raw, nervy material, Harris leaves the posturing of the street behind and promotes pop-and-lock to cinematic new levels. Not that it’s particularly easy to view. “We’ve had audiences walk out,” Albright admits. “People want to hide behind ‘everybody is all right.’ [But] this is who Rennie is as an artist. It’s the spirit first that moves him.”

Beyond his standard repertory, Harris explores African roots in Facing Mekka and (literally) puts a hip-hop spin on Romeo and Juliet in his Westside Story-meets-Shakespeare production “Rome & Jewels.” Instead of the Jets and the Sharks, the rival gangs are hip-hoppers and B-boys who battle contemporary urban demons. And it works: If anything, the classic story seems better served by backwards baseball caps and Brooklyn uprocking than the sweater sets and saccharine duets of the original.

Hip-hop culture dates back at least three decades. According to the unofficial timeline posted on www.b-boys.com, the dance style has its roots in martial arts films and in James Brown’s stage antics. In 1969, Los Angeles street dancer Don Campbell invented the Campbellock, which later evolved into popping-and-locking — maneuvering that involves short, rapid movements of the arms and legs combined with pauses, or freezes.

Breakdancing and Brooklyn uprocking emerged, each with its own set of steps and tricks. Breakdancing responded to aggressive rhythmic breaks in music, when dancers (B-boys and girls) flaunted their most impressive steps. Uprocking featured confrontational dance-offs between individuals or crews. Top rocking, or upright dances, evolved to include footwork or floor rocking (spins and freezes supported by the arms).

Blame it on the Fresh Prince

But, like most art forms better kept underground (read: pure), hip-hop culture inevitably seeped into mainstream music, movies and fashion. Which is why you can watch classically trained dancers add flips and handstands to their routines on the reality-TV hit So You Think You Can Dance. It’s also why, according to hip-hop historian Jorge Pabon, “what was once improvisational forms of expression with spontaneous vocabulary became choreography in a staged setting. A stage performance creates boundaries and can restrict the flowing process of improvisation.

“The same concern applies to the story lines and scripts pertaining to the dance’s forms and history,” continues Pabon. “The mixing and blending of popping, locking, B-boying/girling and Brooklyn uprocking into one form destroys their individual structures.”

But Albright, despite the purist notions suggested in his company’s very name, objects to such rigidity. “I think the next generation of dance is going into a realm of still telling stories — but there’s a story to be told of how we’re all one, and how we can all relate to each other,” the artistic director insists. “Now that I’m doing a lot of choreography by myself, I bring jazz, hip-hop, modern and ballet together.”

Albright has conceptualized his own show, separate from Puremovement, called Same Spirit Different Movement. “It shows there’s one thing in common [in] all the dance. It’s like people — we all share the same spirit, but we’ve all been given individuality. You’ll see something similar in every dance.”

As for shows like So You Think You Can Dance (where viewing audiences often voted for untrained street dancers over ballroom and jazz artists) — well, Albright’s all for that, too.

“I’m excited there was a show just for dance, and I’m excited [dancers] are getting their chance.”

He mentions You Got Served, last year’s movie about a fierce competition between street dancers. Not everyone cared for the Hollywood treatment — but Albright will take exposure in any form.

“I like it,” he contends. “These shows are appealing more to a hip-hop generation. We are in the time of hip-hop.”

From street to stage to living room

You no longer need a square of cardboard and a boom box to enter the world of hip-hop. These days, a DVD player or Off Broadway tickets are as likely to put you within elbow-rubbing range of a B-boy as riding a New York City subway circa 1985. Here are a few of history’s little twists:

• In 1978, Soul Train dancer Charlie Robot introduced his namesake move.

• In 1983, Michael Jackson moonwalked during the “Motown 25” TV special. Audiences speculated that he was a breakdancer.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.