Faith Ringgold has been a painter, writer and performer for half a century. But she doesn’t hesitate to say: “If I woke up white in America, I wouldn’t be an artist.”

One of Ringgold’s ongoing projects is a list of “Racial Questions” on her Web site. That survey, from which the African-American creatrix has culled information over many years, challenges white people to “Imagine Waking up One Morning Black in America!” (Black survey-takers are asked to imagine turning Caucasian.) “I don’t think people want to deal with race on a real level,” says Ringgold. “It’s an itchy subject.”

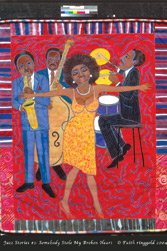

But, as with her painted story quilts—which depict the African-American milieu both in words and in imagery—Ringgold isn’t afraid to tell it like it is. She says she became an artist because she had a story to tell. However, when she finished her autobiography in 1980, “I couldn’t get it published,” she reveals.

We Flew Over the Bridge: The Memoirs of Faith Ringgold was finally put out by Little, Brown and Company in 1995. Still, says Ringgold, “If I were a white person, I wouldn’t have [had] that profound desire [to publish] because my story would already be being told.”

Instead, she offers, she’d be “someone like Hillary Clinton” who works to “undo the problems of oppression.”

A deeper connection

Ringgold hasn’t yet woken up white. At 78, she’s still very much engaged in her own artistic evolution, which began in her formative years growing up during the Harlem Renaissance. Ringgold’s neighbors included painter Aaron Douglas and saxophone player Sonny Rollins, who spiritually informed her work.

Rollins, Ringgold’s contemporary, grew up practicing his sax in the closet so as not to disturb the neighbors. “When he got older he’d go up on the bridge and blow his horn,” the painter recalls. “I thought, ‘This bridge is freedom,’ because he was so determined. He inspired me to be what I wanted to be.” She captured that feeling in her “Woman on a Bridge” series.

Bridges make their way into much of Ringgold’s work. Her online biography points out that she’s lived her entire life within sight of the George Washington Bridge. “Its beauty is very familiar to me,” she remarks in a passage on her Web site. Bridges also symbolize for her a means to get somewhere else, or to bring people together. She accomplished both with her benchmark 1988 story quilt “Tar Beach,” in which a family dines on a rooftop against the cityscape.

Central character Cassie Louise Lightfoot lays on a mattress gazing at the starry sky. In the background, another Cassie is shown flying over the light-strung bridge. Floral fabric squares surround this main image; Ringgold’s hand-printed text runs beneath like an extended caption.

“Tar Beach” was later printed as a children’s book, as were many of Ringgold’s story quilts. She admits that she began quilting to help generate an audience and to land gallery shows: “I wasn’t getting any opportunities to show my work. I was invited to be in the show The Artist and the Quilt in 1980. That’s when I made my first quilt.”

Ringgold has seen the art world come around to quilts as a fine-art endeavor rather than a rustic craft, although that struggle is ongoing, evident in her insistence that “painting quilts doesn’t make me less of a painter.” She also battles for adequate museum representation of African-American artists.

“Some people think any black artist is a folk artist,” she says. “That’s racism—that’s not true.” She explains that many black painters are influenced by folk-art characteristics—including flattening objects, eliminating chiaroscuro (the contrast between light and dark) and centralizing main objects in the composition. But their techniques are no accident.

“I’m not folk, I’m not naive,” she stresses. “I know what I’m doing. When I break the rules, I know I’m breaking them.”

She’ll fly away

She breaks them in life as well as in art. Ringgold relates the story of her 1991 painting “Dancing at the Louvre,” a gorgeously pieced textile in which three young black girls prance beneath the chef-d’oeuvres of the European masters. Some critics are quick to see a social message in the work: Artist Nancy Doyle, on her Web site, suggests “Dancing at the Louvre” is about the “reality of the absence of black people in the European art tradition.”

But Ringgold insists it is “a celebration.”

She’d taken her daughter and granddaughters to Paris in 1961, seeking the hard-to-find “Mona Lisa” in the Louvre. The children were more interested in the ice-cream vendors outside—and so finally locating the famed painting was cause for a victory dance. “I knew you weren’t supposed to celebrate anything in a museum,” Ringgold relates. “I thought, ‘Let’s bring them a little black culture over here.’”

And she continues to bring a little black culture, through her children’s books, nonfiction writing, paintings and art quilts. Part of Ringgold’s mission seems to be putting African-American art in the public eye—something she, herself, did not experience as a young person.

Despite growing up in arts-rich Harlem, Ringgold says she “didn’t know there were important black artists living right up the street from me. I didn’t know the extent of black visual artists because they weren’t in the [school] books. That’s why it’s very important for black artists to have an audience.”

Ringgold’s quilts were fabricated to generate an audience where there was none—but the multimedia pieces are much more than the sum of their cloth, paint and words. “I have tried to use my art to go against whatever oppressive forces have tried to keep me from going where I want to go,” she asserts. That objective is powerfully represented by the many flying figures in Ringgold’s work.

“Flying is to do the impossible,” says the artist. “There’s an old story that the slaves flew out of the plantations.” Her paintings contain that feeling of triumph, helped by bright-happy colors, positive text and uplifting images. Like Ringgold herself, who created opportunity so that her art could hang in galleries, private collections and museums to inspire the next generation, her figures leap decidedly skyward.

“When you have somewhere to go and you can’t get there any other way, that’s when you start flying.”

[A&E reporter Alli Marshall can be reached at amarshall@mountainx.com.]

who: Faith Ringgold

what: Multimedia artist takes part in Asheville Art Museum’s smArt speak: Distinguished Artist Series

where: Diana Wortham Theatre

when: Tuesday, Nov. 18. 7 p.m. ($24/general, $20/museum members, $16/students. www.ashevilleart.org or 253-3227)

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.