Street scene around 5 Walnut Wine Bar by Brian Monteleone, image courtesy of the artist

Traditional art forms, from music to pottery, have a tendency to evolve over the generations. That’s the nature of both humans and heritage work: As much as a technique is preserved, it’s also altered. Crafts are “either museum pieces or part of a living culture,” says woodworker and teacher Drew Langsner.

In some cases, tradition is strictly followed; in others, classic utilitarian pieces morph into to modern, conceptual expressions. And, often, craftsmanship and vision meet in Western North Carolina’s heritage disciplines. “I’ve never been interested in something that’s just art,” says Journel Thomas, a Waynesville-based, self-taught woodturner. His salad bowls are elegant in their simplicity and embellished with his hand-carved designs. “I like it when the functional aspect is still important, but then I like to push it beyond that, so it’s not just a functional object but has some artistic emphasis to it,” he says.

Turned and carved butternut salad bowl with leaf carving, made by Journel Thomas. Photo courtesy of the artist

Turned and carved butternut salad bowl with leaf carving, made by Journel Thomas. Photo courtesy of the artist

The handmade life

Thomas is not exactly from a lineage of woodturners, yet craft has long played an important role in his family. Thomas’ grandfather lived in the Appalachian mountains of Virginia and built the furnishings and implements that his household needed, such as “the kind of woven-bottom chairs that you saw in every mountain home. He made hundreds of them,” says Thomas. And craft provided a way to earn a living: “He blacksmithed, he made tools and tool handles for convict camps. Anything to make a minimal amount of money.”

Thomas’ grandfather also fashioned hand-hewn dough bowls for his wife to use for kneading bread. That was decades ago, but when Thomas taught his own father, Alvin Thomas (now in his 80s), to turn wood, Alvin was drawn to the memory of those bowls. First he and Journel developed the technique for the traditional craft, then Alvin added his own flourishes.

“GuggenCache” desk organizer by Caryl Brt, image courtesy of the artist

“GuggenCache” desk organizer by Caryl Brt, image courtesy of the artist

Journel is married to woodworker Caryl Brt. “We live in a manner that’s 80 years ago,” he says, adding that many serious crafts people share that lifestyle. It’s about building or making what’s needed and “having an everyday connection to your life and the things that enable your life. Out of necessity, you develop a broad set of skills to navigate that.”

While Journel might have much in common with his grandfather, he also understands that both subsistence living, or homesteading, and the passing-down of traditions, are largely things of the past. “I don’t think you can have craft without people being exposed to it and educated in some way,” he says.

Brt, representing the female minority among woodworkers, studied both woodturning and furniture-making in the Professional Crafts program at Haywood Community College. Highly self-motivated, Brt, who grew up in Nebraska, says that from a young age, “Any interest I had, I’d get a job doing it for a couple of years.” She worked as a car mechanic and a railroad brakeman, among other trades. “I’ve always liked the rough-and-tumble stuff,” she says. “I’m not much of a homemaker.”

She does, however, make things for the home. “I started out just doing turning, and I made a good, steady living, but I got tired of doing bowls,” she says. Brt expanded her repertoire to include lamps, mirrors, curvy spatulas and a series of streamlined desk organizers. She also works in conceptual forms (such as her “Better Luck Next Time” voting machine, a response to the 2000 Florida election re-count) and sculptures involving seed pods and handmade paper.

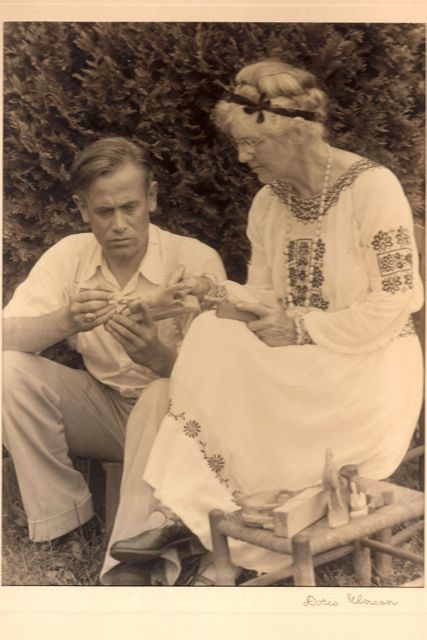

Photo courtesy of John C. Campbell Folk School

Photo courtesy of John C. Campbell Folk School

Where necessity ends and art begins

Resourcefulness is inherent to mountain culture and heritage craft, which both evolved out of necessity. “There are few handicrafts in the Southern Highlands in which wood does not play a very significant part.” Craft-revival champion Allan Eaton made this statement in his 1937 book, Handicrafts of the Southern Highlands. Because the hardwood forests of the Eastern U.S. once stretched from the Mississippi River to the Atlantic Ocean and from Pennsylvania to northern Georgia, it made sense that whatever needed to be made (a table, a loom), could be fashioned from easily sourced timber.

That’s the simplified version of how crafting began in WNC — not as a hobby or an artistic pursuit, but as the means to an end. Want a bowl? Carve one. Want to sit down? Build a chair.

Photo courtesy of Penland School of Crafts

Photo courtesy of Penland School of Crafts

“The mountain sitting chair is a classic,” says Jan Davidson, director of the John C. Campbell Folk School. “It’s mostly hand-carved on a shaving horse with a draw-knife.” The seats are woven using basketry techniques, another classic Appalachian craft: “Those traditional forms haven’t changed much because they’re so good.” (Case in point, Woody’s Chair Shop, in Spruce Pine, is a family business dating back seven generations and more than 200 years.)

But, while tried-and-true forms endure, the know-how to create them does not. Davidson says there’s speculation that the arrival of the railroad signaled the decline of handicraft skills. “We tend to think of it as necessary up to some date and after that it was art,” he says. “But it’s always been both.”

Today’s makers, Davidson says, are putting as much passion into their work as craftspeople did 100 years ago. And would-be crafters have sought out educational institutions for the better part of a century. The folk school, located in Brasstown, launched its programs in the 1920s; Penland School of Crafts, in Penland, was founded in 1929 and has offered woodworking since the 1960s; HCC has offered its Professional Crafts program for more than 30 years.

Worldwide woodshop

Another local learning center is Country Workshops, run by husband-and-wife team Drew and Louise Langsner. They had been living in San Francisco for more than a decade before taking a year to travel through rural Europe. That was in the early 1970s. Drew spent the last three months of that trip working as an apprentice to a cooper, or wooden-barrel maker, in the Swiss Alps. Back in the U.S., the Langsners decided to try the East Coast. “In 1974, we drove a 1952 Chevrolet truck with a little trailer to Madison County, up the exact driveway where we are today,” says Drew.

A few years later, the Langsners opened Country Workshops on their property. The school offers room and board and, currently, five-day class sessions for groups of four students. “We call what we’re doing traditional woodworking with hand tools, but actually we’re very contemporary,” says Drew. “We’re not at all isolationists.”

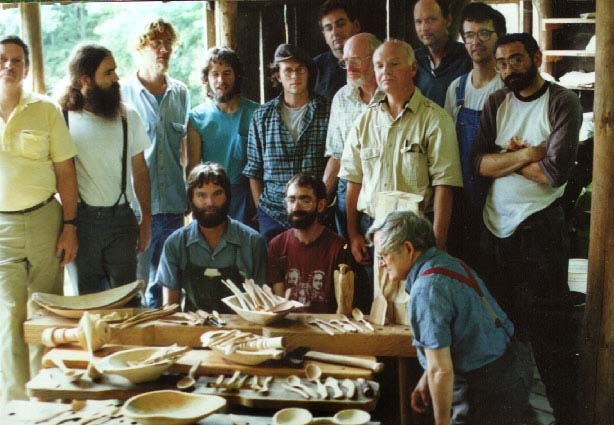

Photo courtesy of Country Workshops

Photo courtesy of Country Workshops

He points out that while craftspeople historically worked in relative solitude, “Nowadays, when you turn on your computer, you can see what spoon carvers in Wales are up to.” Since its inception, Country Workshops has embraced mountain traditions along with worldwide influence: A 1978 class featured both Shelton-Laurel log builder Peter Gott and Swedish bowl-carver Wille Sundqvist.

“In those early years, we were always learning from different neighbors,” says Drew. “Part of what made it really exciting was that the people around here were still basing their lives on skills of self-sufficiency.” He and Louise were also interested in that same lifestyle, from gardening and building a cabin, to making traditional chairs.

Drew says that they came to realize their older Madison County neighbors were “the last of a generation among whom it was common to do these kinds of crafts.” While Country Workshops does its part to pass along some of those age-old techniques (rustic Windsor settees and post-and-rung rocking chairs are class offerings), Drew shares his thoughts on contemporary woodworking through the school and his own work. “I’m hoping that people can make the connection of how we get to these new things and not lose the value,” he says. Integrity and longevity are important factors.

“If you go to the Folk Art Center, what you see there is high-quality work, but very little of it, anymore, is really traditional,” says Drew. “Much of the best of the work shows an understanding and an incorporation of the values and some of the insights of those old traditions, that can be carried on.”

Carved cherry salad bowl with fern design by Journel Thomas, image courtesy of the artist

Carved cherry salad bowl with fern design by Journel Thomas, image courtesy of the artist

Carving out a niche

While some craftspeople pursue a métier, others learn by doing. Asheville-based woodcarver Brian Monteleone says that having no formal education might just be an advantage: “There are no rules or directions,” he explains. “There’s nothing I’m trying to reproduce.” His first gallery show was in spring 2013 at 5 Walnut. Among the work he’s made is a carving of that wine bar and art space.

“The pieces that I do are more business-oriented Asheville scenes,” says Monteleone. He’s also been working on a number of New York-based cityscapes, such as a panoramic view of Manhattan island, and neighborhood portraits including apartment buildings complete with antique water towers. He susses out the personality of the scene by interviewing locals and making sketches. Then, Monteleone commits his vision to wood.

Carving of Asheville’s Flat Iron building by Brian Monteleone, image courtesy of the artist

Carving of Asheville’s Flat Iron building by Brian Monteleone, image courtesy of the artist

The carver got his start 20 years ago, while visiting his family’s hunting cabin in upstate New York. “While everyone was out hunting, I picked up a chainsaw and a log and spent the week making a life-size Indian,” he says in his bio. He was artistic through high school and college: “My whole life is wood. I do contracting and renovations,” he says. “I know that product.”

Still, the road to becoming a semi-full-time artist has been a long one. More than a decade ago, he took a year to pursue carving full time, but struggled with charging for his work. “The taste of money involved with art work was so disgusting, I put everything down for two years,” he says. (Brt, on the other hand, does not mind dealing with the financials of her occupation. Of HCC she says, “They actually created a new kind of system where you could walk out of there and work for yourself.”) This year, though still uncomfortable with the selling process, Monteleone has made a tentative peace with the business aspect of being an artist.

While he’s refused to make the requisite chainsaw bear, Monteleone has completed larger-than-life pieces including a baseball pitcher for a public art project, and a classic cigar store Indian for a private commission.

So, do Monteleone’s carved street scenes share a heritage with Journel’s salad bowls? That question is up for debate, but the desire to create — for art’s sake or for practicality — makes sense to Davidson. “Probably the reason people do this now, when it’s completely a choice, is because making things makes them feel good,” he says. “Some people do it with cooking, some people do it with fishing, some people do it making a wood carving. It’s where you create a special state that’s way beyond just the product.”

Davidson adds, “It’s time well-spent.”

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.