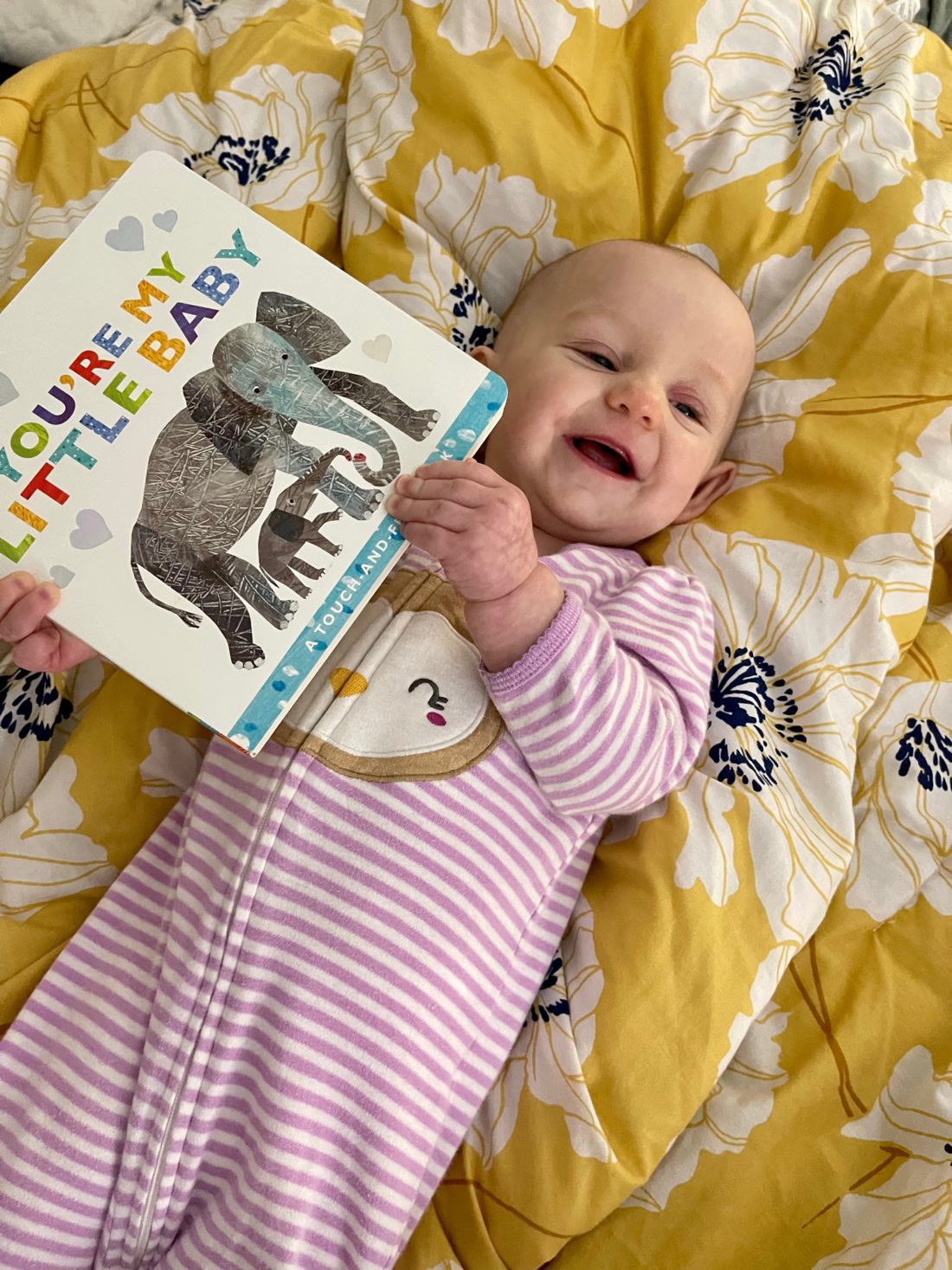

Katy Jane McCurry is 8 months old and already has an enviable library of books. Many were gifts from her mother Emily’s baby shower. But three of the books came from the family’s visits to Dr. Traci Lombard at Mountain Pediatric Group.

Pediatricians aren’t getting into the bookselling business; the books are courtesy of Reach Out and Read, a nationwide nonprofit that is expanding its footprint in Western North Carolina.

ROR has a simple model of literacy promotion: Providers give a book to a patient during a “well child” visit. “The doctor will talk to the parent about the importance of reading and tell the parent, ‘Hey, we’re prescribing this book to you,’ just like they would prescribe medicine,” explains WNC program manager for Reach Out and Read NC Leslie Putnam.

According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, children need seven well-child visits between birth and age 4. (ROR gifts books to children up to age 5.)

Katy Jane’s first book has high-contrast images, her mom, Emily, who lives in Haywood County, tells Xpress. The black background and neon-colored animals are developmentally appropriate for her baby’s brain. “My daughter was fascinated with it because of the very bright colors against the very dark background,” she says.

A second book, You’re My Little Baby by Eric Carle, depicts animals at the zoo and feature some pages with mirrors on them. “It’s super cool as a parent to watch their little brains work,” McCurry says.

The program’s history

A group of doctors at Boston Medical Center founded ROR in 1989. And since 1991, it’s been the subject of peer-reviewed research on literacy interventions for children.

In 2020, the federal Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services approved a partnership between ROR and the N.C. Department of Health and Human Services, which allowed the program to use Medicaid funds.

The partnership allows states to use matching funds to support programs that help children, in particular children who are eligible for Medicaid or Children’s Health Insurance Program, according to a NCDHHS press release. ROR in North Carolina can access $3 million in federal matching funds over two years.

ROR began in North Carolina in 1997, says regional director of communications Suzanne Metcalf, and it has served 231,045 children here since the program began. The impact report for fiscal year 2021 notes 1,826 trained providers in the state. (She declined to share the number of books dispersed.)

Any health care provider who conducts well-child visits can participate. This includes pediatric offices, family doctors, community health centers and local health departments, Putnam says.

In Buncombe County, eight clinics participate while Henderson and Haywood counties have six and three participating clinics, respectively. (The Mountain Area Health Education Center trains residents in the ROR model, making it one of the 70% of family medicine programs in North Carolina to participate.)

The DHHS partnership enabled the program to expand its presence in the western part of the state to counties including Rutherford, Yancey, Mitchell and Avery, Putnam says. As of August, over 70 clinics in WNC participate.

Doctor’s orders

The primary care provider (usually a pediatrician) enters the exam room with an age-appropriate children’s book. The provider demonstrates how to read aloud to a child in a developmentally appropriate way, like showing how to turn a page or asking questions about colors. The child gets to keep the book and leaves with a “prescription” to read regularly with a caregiver.

“When [Dr. Lombard] gives me the book, she explains why she thinks it’s cool and why it’s important,” says McCurry. “We understand why we’re getting it but also why we should be encouraged to actually use it.”

Participating clinics start at birth, and health care providers look for developmental milestones with each visit, like whether the child holds a book right-side up. “Maybe you hand a book to a 4-year-old and they don’t know what to do with a book,” explains Putnam. “That gives you some clues that maybe they’re not being read to.”

At 15 months of age, most kids will show an interest in a book if they’ve seen someone else hold one, according to USDHHS. And at 18 months of age, most kids will be able to look at a few pages of a book. By 30 months, a child should be able to turn the pages of a book, says the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. And by 4 years old, a child should be able to “tell what comes next in a well-known story” and name colors.

Dr. Ann Farash first became acquainted with ROR as a military doctor stationed in Biloxi, Miss., when national medical director Perri Klass spoke to pediatric residents about the program. Years later, Farash became involved in the program in 2013 in North Carolina and helped bring it to Transylvania County.

When asked how she counsels a caregiver as she gives a book, Farah says, “I say read, read, read to your child!”

She continues, “It is said that books are both mirrors and windows. Children are developing their identities; they cannot be what they cannot see.” Both offices of Hendersonville Pediatrics, where she works, participate in the program, Farash says.

ROR’s purview isn’t educating caregivers about screen time or dissuading the use of electronic devices. Nevertheless, the subject arises when reading is discussed, Putnam explains, and that presents an opportunity for the provider to suggest to the child and caregiver “for 30 minutes out of every day, instead of doing an iPad, let’s do a book.”

A love of reading

Another goal is that reading with a child will become a routine and will foster a love of reading on its own.

Clinics source their children’s books directly from publishing company Scholastic and distributor All About Books using ROR funding. Both offer lots of choices — “everything you could possibly have a children’s book about,” says Putnam. (Farash says she loves giving any book by Dr. Seuss.)

A picture book currently popular with health care providers is Ruby Finds a Worry by Tom Percival. “One day, [Ruby] finds something unexpected: a Worry,” explains the Bookshop.org description. “It’s not such a big Worry, at first. But every day, it grows a little bigger … and a little bigger …Until eventually, the Worry is ENORMOUS and is all she can think about.”

Gifting Ruby Finds a Worry helps providers introduce pediatric mental health issues, particularly regarding the COVID-19 pandemic, Putnam says. It helps with “those tough conversations with parents that might otherwise be awkward or feel intrusive,” she explains.

And in order to reach Latino families, the program provides books in English or Spanish. (Nationwide, 78% of ROR programs serve families whose primary language is Spanish, according to the national headquarters.)

Of course, there’s another big benefit to giving a child a book during a checkup:

“It helps that the child knows the book is coming, and so it makes the doctor less scary,” says Putnam. “They know, ‘Oh, I’m going to go get a book!’”

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.