I have a friend who I sometimes think exists mostly to prove—even though he’s a few years my junior—that there are more curmudgeonly folks in the world than I. (Unfortunately, he hasn’t a name that rhymes with anything like “cranky.”) The other day he was celebrating the existence of a highly dubious article on the tanking of summer blockbusters this year (at least five of the films cited were not big-budget flops, just common garden flops). I took issue with this on the basis of factual wobbliness and the fact that a lot of the summer crap is what helps to keep the good stuff viable. The whole thing then escalated into the assertion that it wouldn’t matter to him if they never made another movie, which, of course, served to escalate the argument even more.

The argument isn’t in itself the point here—and I certainly have no desire to continue it. It’s more the fact that there’s an amount of various—sometimes nostalgic—passing instances of something akin to what’s called “Golden Age Thinking” in Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris, which is a current—and quite excellent—movie that tackles the whole “things used to be better” mindset head on.

The whole “Golden Age Thinking” notion is nothing new under the sun—or even under the Paris moon. It’s always been around, and in art dates back at least to 1885 with Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Mikado in the song “As Some Day It May Happen” with its reference to “the idiot who praises, with enthusiastic tone, all centuries but this, and every country but his own.” Midnight in Paris actually manages to address both issues, since its main character, Gil (Owen Wilson), is fixated on a time he never knew in a city that is foreign to him. (Interestingly, Allen manages to have his cake and eat it by coming down on the side of the city, but that’s a separate issue anyway.)

We’re all, I suspect, subject to the “Golden Age” mindset one way or another. You encounter it whenever you see phrases like, “They don’t make ‘em like they used to,” an assessment over the dismal state of motion pictures that probably started somewhere around 1915. What it generally fails to take into account is that the movies the speaker is decrying the lack of were almost all as good as they are because the people making them went out of their way not to “make ‘em like they used to.” If—as so many people peculiarly seem to feel—your barometer for how great movies used to be is Gone with the Wind (1939), it’s worth remember that most of the movie industry—and a lot of pundits—were dead set against the whole idea. It was too long and it cost too much. The idea was that a movie like that could never make back its money. Even after it opened and was a huge hit, that notion was still be nursed along.

You also encounter it whenever people who are possibly a little too sold on their childhoods, but that’s a kind of personal nostalgia. It’s related, of course, and in some ways it can be more annoying. If you have relatives who forward emails about how great it was to grow up in the 1950s, you know what I mean. I know I have a tendency to romanticize the 1964-1975 filmmaking era.

Yes, it was the era when movies broke from the constraints of the studio system and it saw the rise of the idea of the superstar director, especially when the ratings system came into being in 1968 and studios—or what was left of them—were desperate for something new and that paved the way for new filmmakers and the experimentally minded. (It’s kind of the 1960s equivalent of the dawn of sound. Industry shake-ups are sometimes good things.) But it’s also the era I grew up during and I’m sure that informs my sense of it, too. Plus, while it was responsible for a lot of good movies, it generated a lot of crap as well. The trick about eras that are past is that it’s very easy to weed them down to the good stuff and think that’s all there was. It’s similar to the idea—based entirely on exports—about how much better British TV is to American TV. Spend a few weeks in Britain and try watching the overall run of programming. Ye gods.

That’s the big pitfall of all “Golden Age Thinking.” Not being there at the time—or carefully editing your memory—it’s easy to overlook the often mind-boggling rubbish that was part of that time. When I was pretty young, I was convinced that almost everything made between 1920 and 1945 was good. The fact was that it was mostly the good stuff that had managed to stay afloat with the passage of time. We think of the great silent film comedians in terms of Chaplin, Keaton, Lloyd and Laurel and Hardy—and just possibly Harry Langdon. That’s fine. There’s a reason that folks like Snub Pollard and Larry Semon are all but unknown today. As I write this, TCM is running a brace of forgotten early 1930s movies. It’s easy to see why they’re forgotten—apart from archaeological curios.

A while back when I made a tentative case for 1932—as opposed to 1939—as the greatest year in the history of the movies, I was basing that on the cream of the year. I certainly wasn’t talking about The Monster Walks or The Cohens and Kellys in Hollywood (yes, there is such a thing) or Haunted Gold or The Thirteenth Guest or maybe 50 other poverty-row titles from 1932. For that matter, I wasn’t basing it on most of the pap that was being churned out by MGM. Somewhere in the neighborhood of 1500 movies were knocked out that year—and I’m willing to bet that most of them have vanished into obscurity for generally pretty good reasons. (There are always exceptions.)

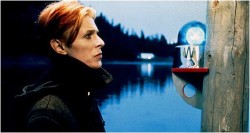

Recently, Roger Ebert reviewed the re-issue of Nicolas Roeg’s The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976), “It’s very much a product of the 1970s, when idiosyncratic directors deliberately tried to make great films. A production of this style is almost unthinkable today; it’s too challenging and abstract for the Friday night mobs and requires too much thought.” That’s true—and, in fact, it came at the tail end of that era—but it’s hardly the whole story. Yes, it was a major release. It had a huge media push—including a glossy article about it in Playboy. It played in plain old regular theaters and multiplexes (as they were then). It was a wide release (which meant something very different then).

This is all true—and it was great—and it was moment in time we’re not likely to see again. One thing this doesn’t tell you is that it came with a price. When The Man Who Fell to Earth played in all those venues, it was 20 minutes shy of what Roeg intended. It didn’t see light of day in its proper form till it hit the 16mm rep circuit a few years later. This wasn’t an isolated incident in the days of art film in the mainstream. Roman Polanski’s The Fearless Vampire Killers (1967), Ken Russell’s The Devils and The Boy Friend (both 1971) were also victims. I think it unlikely they were the only ones. These happen to be titles I know off the top of my head. Even the “good old days” had their problems.

Was it a better set-up? Oh, very probably. It effectively blurred the line between art movie and mainstream. The upshot of all this is that thousands of people who would never have gone to an art movie were exposed to them—and in some cases the experience stuck. I’m equally sure that in some cases, the audience walked away scratching their collective heads, but they were no worse for the exposure. I’m personally glad this happened when I was starting to immerse myself in film, but I recognize the limitations of the appeal of art films in the mainstream.

We have a different dynamic now, and it’s not entirely devoid of art house crossovers. Locally, films like Wes Anderson’s The Royal Tennenbaums (2001), Michel Gondry’s Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004) and Wes Anderson’s The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou (2004) made it into regular theaters. But it’s worth remembering that the Fine Arts Theatre rescued Gondry’s Be Kind Rewind (2008) from a disastrous multiplex opening in Hendersonville (which may have had more to do with Hendersonville than the multiplex aspect). Plus, Anderson’s The Darjeeling Limited (2007) had a more than healthy run at the Fine Arts. Similarly, the much-predicted disaster of Rian Johnson’s The Brothers Bloom (2008) was anything but that as the innaugural art title at The Carolina.

So I don’t mind the move to art-house venues. I’m actually seeing more art titles first run now than I did in the 1960s and 1970s. But I realize that we’re in an unusual position in Asheville. We have one two-screen art-house theater in the Fine Arts and we have one independent multiplex that devotes a number of screens to art titles. For a town the size of Asheville, that’s pretty remarkable. It would be remarkable in a town twice this size, if it comes to that. Art film speaking, we’re pretty much in clover—and I realize that a lot of places aren’t. And that is a downside to the specialized venue mindset. But it’s what we have—and it keeps art and offbeat movies alive. And it does a more respectful job of it than mainstream releasing did in those halcyon days gone by. So it ain’t all bad.

And what about the state of movies? Well, it would matter to me if they never made any more films. There are still people out there with things to say and interesting ways to say them. There are people out there with things to say and interesting way to them who we haven’t even heard about yet. I’d like to see that. Have all the good movies been made? I doubt it. And how will our own era shake out 30 or 40 years on? I very likely won’t be around to find out, but it’s the sort of thing you just can’t see from here. But when The Smurfs and Yogi Bear have been wiped from memory, the last Transformers movie has lumbered off to the junkyard and the final lousy Kate Hudson rom-com is long gone, our own era may look very different indeed.

“I took issue with this on the basis…that a lot of the summer crap is what helps to keep the good stuff viable.”

Please explain this, and given an example.

Are you saying the “good stuff” would not be viable without seeing the crap to compare it against? I would strongly disagree. I only saw a half-dozen films this summer, all of which I enjoyed, and still thought “Midnight In Paris” was a wonder of a film, despite being generally indifferent, if not outright hostile, to most of Woody Allen’s work and worldview. Good films stand on their own merit, not on the comparable crappiness of others.

Are you saying the “good stuff” would not be viable without seeing the crap to compare it against?

Good Clapton, no. I’m saying that those big money-makers make it possible for studios to risk the smaller quality films. Look at Midnight in Paris. It’s a success, but in terms of money-making, its US gross is at about $54 million. It cost $30 million. In order to break even — remember the studio pays about half of the ticket price to the theater — it would need to gross about $60 million. The big pictures help support the specialty branches like Sony Pictures Classics.

I always find this argument a bit specious. However, considering that ‘my day’ is now, I might well be making this argument in 30 years.

Considering ‘my day’ has encompassed There Will Be Blood, Goodfellas, The Prestige, True Grit, Batman Returns, Brick, The Departed, Harry Potter and the Prizoner of Azkaban, Brokeback Mountain, American Beauty, Ed Wood, O Brother Where Art Thou?, Memento, Adaptation, Sweeney Todd, Vicky Christina Barcelona, Shutter Island, Charlie Wilson’s War, The Silence of the Lambs, Gods and Monsters, Inception, Tomorrow Never Dies, A Single Man, Juno, The Quiet American, A Few Good Men, Confessions of a Dangerous Mind, Let the Right One In, Ocean’s Eleven, Chicago, LA Confidential and Up in the Air, just to name a few, I’d say we live in a pretty good time for movies.

Well, you have about six on there I wouldn’t brag about, but I’m not arguing with your overall idea.

Things go in cycles. Look at the 50s vs the 40s and 60s. We are currently in a time where there is probably an overabundance of crap. But the dumb action movie is apparently finally running its course. Special effects don’t wow people any more. Maybe we’ll see a return to real screenwriting and decent plotting again as the studios try to interest the viewers. One can hope.

We are currently in a time where there is probably an overabundance of crap.

Yes, but I do suspect it’s partly because we’re in it and can’t get a perspective from here. Look at 1970, for example. It gave us The Music Lovers, M*A*S*H, Catch-22, Little Big Man, Five Easy Pieces, The Conformist, Performance, The Boys in the Band, Tristana, Brewster McCloud, Leo the Last — to name some of the more interesting titles that occur to me.

But it also gave us Love Story, Beneath the Planet of the Apes, Airport, Tora Tora Tora, On a Clear Day You Can See Forever, Beyond the Valley of the Dolls, The Owl and the Pussycat, Myra Breckinridge, There’s a Girl in My Soup, When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth, Which Way to the Front?, Pufnstuff, The Boatniks, When Women Had Tails, Song of Norway, Norwood, The Cockeyed Cowboys of Calico County and more absolutely awful horror movies than you can shake a stick at (which might be more fun than watching them). I’ll concede some of these are of passing curio value, but that’s a pretty depressing list.

Hey hey hey. Myra Breckenridge is one of the most entertaining things I’ve seen in recent years.

Yes, perspective might change things in the future concerning this era. But 2011 is gonna go down as a terrible year regardless unless things change drastically in the next few months. Ye gods, what an awful movie year.

Hey hey hey. Myra Breckenridge is one of the most entertaining things I’ve seen in recent years.

But would you call it good?

But 2011 is gonna go down as a terrible year regardless unless things change drastically in the next few months.

That I really wouldn’t argue with.

But it also gave us Beyond the Valley of the Dolls

Thems fighting words.

Now with the way they make movies (accountants and committees), I still think we are going to see less and less of these films that are a director’s vision. It looks like they will barely break even on TREE OF LIFE. They would rather reboot a franchise for the umpteenth time than take a chance on a totally new idea. That’s why films like Allen’s and Malick’s need to be supported… they might be of a dying breed.

Now with the way they make movies (accountants and committees), I still think we are going to see less and less of these films that are a director’s vision.

I’m not at all sure that’s true. Whether or not you like those visions is a separate issue, but they’re still out there.

That’s why films like Allen’s and Malick’s need to be supported.

I don’t think anyone’s arguing against that.

“It’s similar to the idea—based entirely on exports—about how much better British TV is to American TV. Spend a few weeks in Britain and try watching the overall run of programming. Ye gods.”

I think this is largely true, but not completely. I am aware of some really good BBC productions that were not exported here, but by and large, having spent some time in Britain (including several days of lousy weather parked in front of a television), they broadcast just as much drek as American television.

I am aware of some really good BBC productions that were not exported here

Most certainly, but most of the really awful stuff doesn’t get sent to us, though I’d argue that Are Your Being Served gets close.

The main reason that Larry Semon is unknown today is that 98% of his films are lost. Semon was originally a cartoonist who became an influential comedian and excellent gag man. He gave Stan Laurel his first big break in films (Laurel would recycle many of Semon’s gags for L & H) and employed Oliver Hardy as his comic foil. Unfortunately he is remembered today for his worst film, a 1925 feature length version of THE WIZARD OF OZ which clearly showed him overreaching himself in an attempt to make feature films in the 1920s. Now that some of his earlier short films such as FRAUDS & FRENZIES (w/Laurel) and THE SAWMILL (w/Hardy) are available for viewing, it’s possible to see just how creative he really was. He died in 1928, at the age of 39, before sound arrived which didn’t help his case for being remembered. His last significant appearance was in Josef von Sternberg’s UNDERWORLD (1927).

I saw a couple of shorts that Blackhawk used to sell and I wasn’t that impressed. I think one thing that hurts him is that he’s not an appealing presence — at least I don’t find him so. I think that one of the reasons — apart from antiquity and the fact that many of their careers ended or fizzled too soon — that a lot of silent comics have not stuck in the popular consciousness has to do with a lack of strongly appealing presence. And that’s often not helped by their often grotesque make-ups. (I wonder how W.C. Fields would have fared if he hadn’t ditched that awful mustache after 1931.) Chaplin, Keaton, Lloyd, and L&H are innately appealing in ways that so many are not. But who knows? Maybe John Bunny is due for a comeback.

There are fewer John Bunny shorts available than there are Larry Semon shorts but the 150th anniversary of Bunny’s birth (2013) and 100th anniversary of his death (2015) are just around the corner so get ready!

I’ve already stock-piled blank DVDs for that eventuality.