A few weeks ago Universal put out a pretty nice set of Bob Hope movies. This Sunday (August 8) TCM offers a truly perplexing mix of some of the best and a lot of the absolute worst of Bob Hope. Maybe that’s fair, though, since perhaps no one ever put so much energy into creating an iconic public persona and then so tenaciously destroyed that image by not knowing when to quit. But there was a time when Hope was a major figure in film comedy, and that’s worth remembering.

To the degree that Bob Hope is remembered today—and I suspect that gets less all the time—it seems to usually be with derision. Truth is there’s really no one but Hope himself to blame. The man had about nine solid years of greatness, followed by a few years with flashes of brilliance—and then a lot of mediocrity and worse. Not only did he persist in churning out increasingly lame movies up through 1972 with the dismal Cancel My Reservation, but his increasingly hawkish right-wing stance managed to alienate a lot of young film buffs at the very time they were discovering and lionizing classic comedy performers like the Marx Brothers, Mae West and W.C. Fields.

It’s impossible to deny that Hope made a lot of bad movies—not just bad, but embarassingly bad. As one of the few people I know who has seen most of Hope’s short films and all of his features (yes, even the elusive 1943 musical-comedy Let’s Face It and the rightfully disdained 1956 attempt to team him with Katharine Hepburn, The Iron Petticoat), I have a pretty good working knowledge of his filmography, and just how bad it got. Some of this can be blamed—as it often can—on a performer becoming too powerful and being given too much control over his career. It’s hard not to note that the first real signs of trouble don’t surface till Hope started taking charge of the production of his movies in the late 1940s. That’s not all of it—some of the Hope produced movies are very good—but combine it with a refusal to acknowledge the passage of time and it’s a recipe for disaster.

Circumstances played a factor, too. Hope’s desire to be taken as a serious actor—which first surfaced in Sorrowful Jones (1949)—had some impact on the trajectory of his career. He parlayed that into The Seven Little Foys (1955), a somewhat seriously intended biopic about Eddie Foy that still contained bouts of comedy and music. But it bore full fruit in 1957 with Beau James, a wholly serious biopic about New York mayor James J. “Jimmy” Walker. It’s not a bad movie, though it’s cursed with a bad case of 1950s-itis in that its 1920s-30s setting is wholly unconvincing. But good or bad, the critics weren’t kind, the film was considered a misfire, Hope was considered miscast, and he retreated to the safety of a largely worn-out formula.

The sad thing about this is that the best of Bob Hope is among the best of film comedy. In fact, if it hadn’t been for Hope and Preston Sturges the world of movie comedy in the 1940s would have been pretty bleak indeed. That’s worth recalling—just as Hope’s work is worth revisiting.

Bob Hope’s film work—spawned by his stage success in Roberta in 1933—was tentative at first. He wasn’t inclined to give up Broadway and only agreed to make some short films at the Long Island studios in New York. The first of these, Going Spanish (1934), was truly dreadful, which comes as no surprise since it was made for Educational Pictures—a misnomer if ever there was one, unless the films could be said to be lessons in how bad movies could be. Hope himself hated it and remarked to columnist Walter Winchell that it was “so bad that when they catch Dillinger they’re going to make him sit through it twice.” Winchell and his readers were amused. Educational wasn’t—and Hope’s contract was cancelled.

Hope fared a little better making shorts for Warner Bros., though not spectacularly so. The best of these shorts is Paree, Paree (1934), a 20 minute version of the Cole Porter stage show 50 Million Frenchmen, which is the studio purchased in the early days of sound—along with star William Gaxton and supporting comedienne Helen Broderick. But by the time the film in 1931 musicals were considered box office posion. So they filmed it with the Porter songs reduced to background score. As a result, Hope got to introduce two Porter standards, “You Do Something to Me” and “You’ve Got That Thing,” in the movies. Somewhat amusingly, the play had to be cleaned up meet the recently introduced production code—not only spoiling some of the choicer lines, but dictating that the racehorse “Pansy” be rechristened “Patsy,” just so nobody got the wrong idea.

It was 1938, however, that Hope made it into features and a contract with Paramount Pictures, the studio most associated with him. He was cast in the supporting role of Buzz Fielding in Mitchell Leisen’s The Big Broadcast of 1938, a film that was meant to serve as Paramount’s comeback film for W.C. Fields after his absence from movies for two years owing to ill-health. Actually, it proved to be Fields’ swan song for Paramount, and most of the accolades went to the sixth-billed Hope—primarilly for singing “Thanks for the Memory” with Shirley Ross. Watching the film now, that’s easily understood because it’s the only point where this disjointed great big hollow glitter-ball of a movie becomes human.

The problem was that the studio had Hope, but they didn’t quite seem to know what to do with him. He was quickly thrust into the George Burns-Gracie Allen musical comedy College Swing (1938), which did him no real favors, especially since it prompted the studio to think that he was a good screen partner for Martha Raye. Apart from giving Hope the “How’dja Like to Love Me?” number with Martha Raye, Hope wasn’t afforded much here. The best comedy comes—not surprisingly—from Gracie Allen as the world’s dumbest student. It looks like a masterpiece next to Give Me a Sailor—a film neatly summed up on its release by one critic noting that “anyone paying good money to see a movie called Give Me a Sailor deserves what he gets.”

Since these weren’t setting the world on fire, Paramount dusted off a 1930 property called Up Pops the Devil, retitled it Thanks for the Memory (1938) and reteamed Hope with Shirley Ross. The results were mildly pleasant. The reteaming was a good idea (Shirley Ross was better match for Hope than Martha Raye), and a new version of the title song and the new song “Two Sleepy People” helped, but the story was something else. It hadn’t been much in 1930 and it hadn’t improved with age.

Never Say Die (1939) was a vast improvement, even if it did reteam Hope with Martha Raye. The great Preston Sturges had a hand in the screenplay, and though Hope’s material appears to have been mostly crafted by Frank Butler and Don Hartman, there’s definitely some Sturgean wit on display here, especially as concerns the way in which the “curative natural” waters of the spa at Bad Gaswasser (a Sturges name surely) are made (by an undrecited Gustav von Seyffertitz). Then there’s Monty Woolley’s brief role as Dr. Schmidt who misdiagnoses Hope as having a condition that will cause him to digest himself into nothingness—a situation the medico sees as his path to fame (“Schmidt and his disease!”).

Hope isn’t badly served himself—and you know that “vessel with pestle” business that everyone’s so gaga about from The Court Jester? It appears here in incipent form as “there’s a cross on the muzzle of the pistol with a bullet and a notch on the handle of the pistol with the blank.” (Then again, it had appeared in a different form back in the 1933 Eddie Cantor film Roman Scandals.) Perhaps the most notable thing about Never Say Die is that it’s the first Hope film to present him in full-blown professional coward mode.

Hope always said his next film, Some Like It Hot (1939), was his worst. Over the years, Bing Crosby supposedly used to bedevil Hope by inviting him to screenings of it. Truth is, it looks pretty good by comparison with most of his later film, but it’s not very good. It’s also surprisingly unfunny and Hope plays an almost wholly unsympathetic character. Hope’s career seemed to be worse than going nowhere, but something was about to change all that.

Hope’s next project was a revamping of the 1922 John Willard stage play The Cat and the Canary, the most famous of all old dark house thrillers. It had been made into a film in 1927 by Paul Leni for Universal. That studio remade it as a talkiie in 1930, The Cat Creeps, which has since fallen prey to the status of lost movie. Reworking it for Hope might not have seemed a natural, but it was. The leading man’s name, Paul Jones, needed changing, since it wasn’t likely Paramount wanted a character with the same name as one of their producers, so Hope became Wally Campbell. The original character was a cowardly fellow who has to become brave in the course of the action—a nice blend of the professional coward of Never Say Die with a new element: Hope as unwilling hero. It would become a strandard characterization.

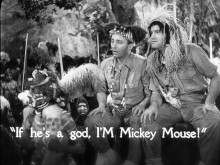

More helpful in its way was going back to the basics of The Big Broadcast—presenting Hope as a wisecracking performer. This would also become stock-in-trade. Many of the movies that followed presented Hope as a small-time actor, a radio personality, a movie star or a vaudeville perforner. These were characters he related to, since he’d been all of them. It also served—especially in this case—to shake some of the dust off the old play by allowing Hope’s character to comment on the mechanics of the plot. Yes, it occasionally undermines the thriller aspects of the story—as when Hope quips, “What some guys won’t do for a laugh,” upon hearing the horrific description of the escaped homicidal maniac known as “the Cat.” But more often than not, the remarks helped carry the film along—and in some ways they’re less intrusive than the broad humor of the play and the silent. Hope responding to the idea that “sometimes the dead come back” with the query, “You mean like the Republicans?” is a lot less damaging than Creighton Hale’s mugging in the silent.

The film was a surprise hit—with the public and the critics—and achieved the rare distinction of being a comedy horror film that never lost sight of either genre. It treated the story itself with a fair degree of seriousness, created a properly ominous atmosphere, generated genuine suspense in its final scenes, and boasted a “Cat” make-up that was genuinely frightening. (The earlier attempts were cheesy to say the least.) More amazing still was the fact that the studio followed suit with another old dark house thriller, The Ghost Breaker, which was pluralized for the Hope version. (Whether the plural refers to Hope and black comic Willie Best or to Hope and leading lady Paulette Goddard or all three in unclear.) It was easily as good as The Cat and the Canary and possibly better. However, another important film separates the two.

A good barometer of where Hope’s career was before The Cat and the Canary hit is the fact that he’s billed beneath Dorothy Lamour on Victor Schertzinger’s Road to Singapore (1940). He clearly has the larger role and is onscreen with Bing Crosby from the very beginning of the film. Lamour comes in a couple reels later and has been given a fairly thankless straight exotic leading lady role—even less challenging than her typical South Sea island adventure pictures. She had the unenviable position of having to play her character as if the film were meant to be taken seriously, while Bing and Bob did whatever they wanted. But she was more popular than Hope. That wouldn’t last, and neither would the billing, nor Dotty getting saddled with a serious role.

Road to Singapore seems pretty calm today—especially when compared with what came in its wake—but it was as a wild surprise in 1940. The chemistry between Bing and Bob was something no one could have anticipated. Similarly, no one could have known that putting the two together would result in a game of one-upsmanship that caused them to depart from the screenplay and ignore the direction. Some of it was ad-libbed, a lot of it was the result of each of them having a gag writer on hand, but it didn’t really matter. What mattered was that it seemed like they were making it up as they went along. Director Schertzinger was good natured about it, realizing he was capturing something unique by giving the boys their lead—even if it made shooting chaotic and the results sometimes a little technically ragged.

What resulted was a silly, sloppy comedy with songs that the public adored. And really it’s hard not to adore Road to Singapore. It was probably even more so at the time. The Marx Brothers and Laurel and Hardy were slipping badly. Even with My Little Chickadee (1940), Mae West had been all but censored out of existence. Only W.C. Fields was holding up. Abbott and Costello hadn’t quite made it yet. The time was perfect for Bing and Bob to inject new life into movie comedy. Road to Singapore allowed them to do that. Its follow-ups—beginning with the next year’s Road to Zanzibar—took it even further. Not only did Zanzibar make Lamour something like a full partner, but it operated on the basis that the viewers knew they were watching a movie—even to the extent of using the idea that characters in this film had seen Road to Singapore as a plot contrivance.

Road to Zanzibar gets my vote as the best of the series (though I have a personal soft spot for Road to Rio [1947]). It’s not as much of a free-for-all as Road to Morocco (1942) or Road to Utopia (1946), but it’s a film that works both as part of the series and somewhat outside of it as the perfect satire of all African adventure pictures. That’s perhaps because the film took a straightfoward adventure yarn, Find Col. Fawcett, and ran wild with it. I think it probably helped to have a model to satirize.

At this point, Hope’s career was in full swing—and it was with a force that carried him through the decade. OK, so Caught in the Draft (1941) was a standard service comedy that wasn’t helped by the presence of Eddie Bracken (nothing ever was), and Let’s Face It wasn’t so hot, but from The Cat and the Canary through The Paleface (1948) there’s not an outright stinker in the lot. There are few comedians who can boast a run like that. And even after 1948, there are definite bright spots.

The Lemon Drop Kid (1951) is a terrific Hope film—even though it didn’t do well on its original release. That was Hope’s fault. He didn’t like the film Sidney Lanfield turned in—despite the fact that Lanfield had made what he felt was his best movie, My Favorite Blonde (1942)—and wanted re-writes and re-shoots. Frank Tashlin was brought in for this. The immediate upshot was that Hope has a Christmas movie that was released in April. Bad timing? Yes, but those Tashlin re-shoots also helped the film no end—and include the “Silver Bells” musical number, which is the most memorable thing in the movie.

Tashlin returned for Son of Paleface (1952), one of Hope’s best films from any era—and his last truly great one. It was wilder and funnier than The Paleface—which was pretty darn good in itself—and is perhaps the closest the movies ever came to creating a cartoon with live action. Considering that Tashlin started out making cartoons, that’s not all that surprising. The film is a non-stop barrage of gags—each crazier than the next and with no regard for even passing reality, a fact the film itself makes note of. When a pair of vultures—who had previously turned into penguins that sang “In the Cool, Cool, Cool of the Evening”—reappear during the climactic chase, Hope shoos them off by saying, “Beat it or you’re gonna make the whole thing unbelievable.”

Unfortunately, it would only be a year later that Hope would come out with his first truly bad movie, Here Comes the Girls, and part of the problem would be central to so much that followed—the refusal to accept his age. Son of Paleface may have presented Hope as an unlikely fresh college graduate, though that can excused on the grounds that it could have taken an incredibly long time for the character to have made it through school. (And it’s no worse than John Ford wanting us to take 54-year-old James Stewart as a recent law school graduate in 1962 with The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance.) Here we get the 50-year-old Hope as a chorus boy and while he might pass for a man in his mid to late 30s, this is simply pathetic. Rather than making Hope’s character funny, it makes him look spectacularly backward—and having him as “the world’s oldest chorus boy” doesn’t help.

It wasn’t all bad, not by a long shot. There would be some great moments and some pleasant films up through Call Me Bwana in 1963, though even that isn’t a very good film. It may in fact be the first movie where I encountered the idea of film criticism. I remember walking by the theater where it was playing and the manager was out front, so my parents asked him how Call Me Bwana was and he called it “typical grade B Bob Hope.” I had to have my father explain that to me (I was eight at the time), but I found out for myself a couple years later when it showed up again as part of a kiddie matinee. Still, it’s a movie I can’t quite dislike—and I don’t think that’s entirely due to the Maurice Binder titles that feature monkeys, though I’m sure that helps.

What somewhat sets Call Me Bwana apart is the fact that it’s not smarmy in the way many later Hope vehicles are, and it looks and feels like a movie. All of Hope’s film work from Boy, Did I Get a Wrong Number! (1966) on look like TV shows that got out of hand. The lighting is flat and high-key, the acting broad, the plotting pure sitcom. It’s hard to believe that both this and the equally awful Eight on the Lam (1967) were directed by the same George Marshall who made The Ghost Breakers, but apparently they were. Of course, it’s also hard to believe that this is the same Bob Hope. It’s also rather sad.

What needs remembering, however, is that it wasn’t always like this. And however much you might loathe the later day Hope efforts, that does nothing to diminish his earlier accomplishments in movie comedy. Yes, there was a time when Bob Hope was cool, sharp and truly funny. He left his stamp on film history and he influenced a generation of comics. Think not? Watch Woody Allen in any of his earlier comedies—even some of his later ones—and you’ll see the professional coward persona all over again. You’ll also find that Allen—for all his intellectualism—owes a debt to Hope’s delivery and sense of timing. Better still, check out some classic era Bob Hope for yourself. The new box set is a good place to start. Most of Hope’s best work is out there for the asking. Take advantage of that.

Wow! That last paragraph is a zinger! As I was reading this essay, I was thinking to myself, “I never cared as much for Bob Hope as I responded to Dave Thomas’ -impersonation of Hope- on SCTV.” My mind invariably want to the brilliant SCTV sketch “Play It Again, Bob” which posits Woody Allen as a huge Bob Hope fan who is compelled to direct his hero in a film worthy of his talent so he’ll get the accolades he deserves. The huge disconnect between them personally (in spite of helpful spirit visitations to Allen by Der Bingle) drives the brilliant comedy, which also mirrors the structure of “Play It Again, Sam.” Have you seen that, Ken?

If not:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8GqbCrsfrfs

I used to have a few of THE ADVENTURES OF BOB HOPE comic books from the early 1960s. I remember one with a cover of Bob standing on the ledge of a building while an irate husband headed his way, the wife saying “Run, Bob, run!” and him saying “I forgot my tennis shoes”.

My favorite gag, also from a comic book (and old even then), was having Bob working for Miracle Pictures “If it’s a good picture, it’s a Miracle!”.

I especially remember the Bob Hope NBC TV specials sponsored by Chrysler (with the 5 year/50,000 mile warranty that covered everything) which were a lot funnier than the 1960s movies. Wow, I hadn’t thought about those in years.

Bob Hope will always be one of my very favorites. I can at any moment in time stop everything to watch Ghost Breakers, My Favorite Brunette, any of the road pics, Monsieur Beaucaire, Princess and the Pirate …. his asides, his timing made the most of his material …. I ignore the glut of B material that is unworthy of his genius….he had done enough by the time 1950 rolled around to be a legend

Have you seen that, Ken?

If I had, I’d forgotten it. (Now, where is John Candy’s Orson Welles introducing Sandwich on the Orient Express with “It isn’t Citizen Kane, but then what is?”) The sad thing is it’s probably a pretty fair assessment of what would have happened — except maybe the ending.

I used to have a few of THE ADVENTURES OF BOB HOPE comic books from the early 1960s. I remember one with a cover of Bob standing on the ledge of a building while an irate husband headed his way, the wife saying “Run, Bob, run!” and him saying “I forgot my tennis shoes”.

That’s pretty racy for a comic book presumably aimed at children. I remember the comics in a vague sense, but the only gag I can remember involved Bob confusing abominable with abdominal in a story about the Abominable Snowman.

I especially remember the Bob Hope NBC TV specials sponsored by Chrysler (with the 5 year/50,000 mile warranty that covered everything) which were a lot funnier than the 1960s movies

Assuming we’re talking about the ones that had plots and not the variety shows, I’d be curious to see those again. I remember liking them when they were new and I was a kid. I wonder how they’d hold up.

I ignore the glut of B material that is unworthy of his genius….he had done enough by the time 1950 rolled around to be a legend

I wouldn’t argue that, but it’s hard to ignore those movies when tributes like the one currently on TCM insist on including them. The only reason I can think they’re part of the 24 hours of Hope is that TCM owns the MGM and UA product and has to tap Universal for the choicer Paramount titles. At least the good stuff is all in a block between 1:15 and 11:15 p.m.

TCM shows how little they care for Bob by running the B crap that is even unworthy of TCM …. None of those movies can be classics in any stretch of the imagination …. they don’t seem to let the limitation of their library limit their ability to use good judgement toward the movies and the legends … it is like running a John Wayne fest and only using Three Mesquiteers or the Conqueror

TCM shows how little they care for Bob by running the B crap that is even unworthy of TCM …. None of those movies can be classics in any stretch of the imagination

No argument there.

they don’t seem to let the limitation of their library limit their ability to use good judgement toward the movies and the legends

It depends on who they’re doing. It’s easy for them to do a solid 24 hours of, say, Errol Flynn because they own all the good stuff. It gets trickier when they go for Paramount, Universal, or Columbia stars.

If he’d have been ignorant enough to be a liberal you’d have written just how GREAT his work was.

Did you actually read past the second paragraph? For that matter, did you comprehend what I said there? I merely pointed out one of the reasons Hope was overlooked by the same kids who helped revive the appreciation of other classic era comedians.

Instead, you Socialists write about the crap put out by dolts like Chevy Chase who has “STUPID” down real good but NEVER quite attained “Comedic”.

You really know nothing about me if you think I have ever praised Chevy Chase.

It depends on who they’re doing. It’s easy for them to do a solid 24 hours of, say, Errol Flynn because they own all the good stuff. It gets trickier when they go for Paramount, Universal, or Columbia stars.

TCM needs to work out agreements to serve star, studio and audience …

TCM needs to work out agreements to serve star, studio and audience …

Ideally, sure, but in practical terms, shortcomings to one side, they’re the best friend classic movies have had since the halcyon days of AMC.

Bob Hope was in Danang in 1969 when I was there. At least the troops appreciated his shtick, though I’m pretty sure that Joey Heatherton was the bigger draw. Well actually anyone who came over to entertain us was appreciated. Looking back on it, yeah he was well past his prime. I loved Bob Hope when I was little but by the time I hit my 20s he was boring.

But this brings up another sort of bigotry. Film buffs wouldn’t review Hope’s earlier work because of his later right wing stances? What kind of reason is that? If one is trying to learn about effective comedy one needs to study effective comedians despite their political leanings. You can learn more from people you disagree with if you have the willingness to reevaluate your own assumptions. You won’t do this with people who reinforce your ideas.

And Mark, if your political skin is that thin you need another hobby. Avoid movie critics entirely because most of them will make you far more annoyed than Mr Hanke will.

Hope tossed in right wing one liners into even his best films. Lines like “Do you believe people can come back from the dead?” “You mean like Republicans?” That’s from Cat and the Canary.

The Road movies…I dunno. I used to find them funnier when I was about 11 or 12 and hadn’t seen some REALLY out there comedy. Another critic (Dennis Schwartz?) said the Road movies are “conservative anarchistic comedy” if there is such a thing. I get what he means. Compared to the weird Universal Fields flicks, or stuff like Hellzapoppin, the Road movies are reasonably mild fare. Of course, that might be why they were more popular.

Film buffs wouldn’t review Hope’s earlier work because of his later right wing stances? What kind of reason is that?

Well, no one was really reviewing things at that point in any significant capacity. I think the resistance was mostly evident in that his movies had no draw. You have to remember that these kids weren’t just embracing the movies, but were viewing the performers as people they could identify with. I suspect it helped that Groucho went around saying some pretty outrageous left-wing things. He and Fields and West were viewed as anti-establishment. Hope was looked upon as establishment. But that’s only part of the story. You have to factor in the absolute crap was still shoving into theaters. It wasn’t a good mix for the kids of that era.

And Mark, if your political skin is that thin you need another hobby. Avoid movie critics entirely because most of them will make you far more annoyed than Mr Hanke will.

I don’t much mind being called ignorant, pretentious or a moron, but I take great offense at being accused of praising Chevy Chase.

Hope tossed in right wing one liners into even his best films. Lines like “Do you believe people can come back from the dead?” “You mean like Republicans?” That’s from Cat and the Canary.

That never struck me as right wing — if anything it carries the opposite feeling. Mostly, it conveys the then apparent permanent status of FDR. Now, the line in The Ghost Breakers about Democrats is another matter, but even there I think it’s less political than just a gag. (There’s a jab at both parties in Call Me Bwana.) You have to remember that Hope was friendly with every president from FDR through Clinton.

Another critic (Dennis Schwartz?) said the Road movies are “conservative anarchistic comedy” if there is such a thing. I get what he means.

I can’t say I do.

Compared to the weird Universal Fields flicks, or stuff like Hellzapoppin, the Road movies are reasonably mild fare. Of course, that might be why they were more popular.

It might also be that they were generally better. Only one Fields movie — Never Give a Sucker an Even Break — is really weird. And while Hellzapoppin’ and, in a different sense, Crazy House are peculiar, they suffer from stopping dead for unrelated musical numbers. Plus, for me at least, a very little Olsen and Johnson goes a long, long way.

Hope tossed in right wing one liners into even his best films. Lines like “Do you believe people can come back from the dead?” “You mean like Republicans?” That’s from Cat and the Canary.

Well, lefty one-liners get thrown into just about everything. People shouldn’t be so touchy when it goes the other way.

And Ken, I understand fully your offense at being accused of liking Chevy Chase. I did like Xmas vacation though. Not as much as that Ken Russell movie “Gothic” you shanghaied me into watching (twice in a row). Now I’ve got “Valentino” in hand. Will DrSerizawa become a Russellphile? Stay tuned.

Well, lefty one-liners get thrown into just about everything. People shouldn’t be so touchy when it goes the other way

For me, the question is, “is it funny?”

Will DrSerizawa become a Russellphile? Stay tuned.

I’ll buy you a ticket to Tommy on Sept. 1 if you’ll come to Asheville.