Last week was Father’s Day and because of my daughter, I ended up spending a good bit of the past week watching Bing Crosby movies. In other words, she sent me the most recent Bing Crosby Collection. It’s actually a very apt choice, since I mostly owe my lifelong love of Der Bingle to my father, who not only introduced me to Crosby, but slightly resembled him and sang very much in the same style. (At the same time, he wrong-headedly preferred—oh, my, no—Frank Sinatra.)

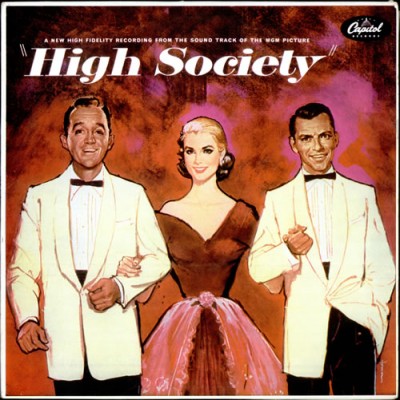

The truth is I was introduced to Bing and Frank at the same time via the soundtrack album for High Society (1956), which means that I was also introduced to Louis Armstrong, Cole Porter, and—to a much lesser extent—Celeste Holm and Grace Kelly at the tender age of about two. By the age of five, I had co-opted the album. My guess at this remove is that it was the first album I ever “owned.” I do not recall if I was actually given it, or if it just gravitated out of my parents’ records and into my own. My favorite was “Well, Did You Evah?”—a song I could have understood very little of at the time, even if I knew all the words.

Regardless, one thing evolved into another and finally got me to last week and “The Bing Crosby Collection.” This is actually the second such collection. The first collection consisted of Waikiki Wedding (1937), Double or Nothing (1937), East Side of Heaven (1939), If I Had My Way (1940), and Here Come the Waves (1944). It’s not exactly a primo collection, but Waikiki Wedding comes under the heading of an essential. Universal—who owns most of Crosby’s movies, since they bought nearly all Paramount films made between 1929 and 1949—is good at this kind of packaging.

This new set is better. OK, so Universal pulled their usual gag of duplicating titles you might have, since they included Norman Taurog’s We’re Not Dressing (1934), which was already a part of their “Carole Lombard Glamour Collection.” I suppose it’s possible that you might be a Crosby fan and not a Lombard one, so I’ll cut some slack. And I can’t really complain about the inclusion of A. Edward Sutherland’s Mississippi (1935), since the only reason I already have that title is because I got fed up waiting for Universal to cough up the rest of their W.C. Fields titles and bought the Region 2 set from the UK. This does mark its first release in the States. On the other hand, I can complain that they didn’t include Bing’s first feature—and one of his best 1930s films—Frank Tuttle’s The Big Broadcast (1932). But instead of kvetching about what’s not here, let’s look at what it does have.

First up is Wesley Ruggles’ College Humor (1933)—a movie that really comes under the heading of more peculiar than actually good. I can—with a little stretch—accept the idea of Bing as a college professor, since the one class we see him teach consists of him singing “Learn to Croon” to his class, especially since he incorpates bits of “Just an Echo in the Valley,” “Please,” “I Surrender, Dear,” and “Just One More Chance”—all of which happen to be earlier hits. Accepting Jack Oakie and Richard Arlen as college students is a good deal more difficult. Buying Joe Sawyer (under his real name Joseph Sauers) is even harder, despite him actually being the youngest of the three. (He doesn’t look it.)

Probably the most troublesome thing about College Humor—apart from the fact that it’s put together like a $12.95 tuxedo—is that it isn’t really very humorous. It’s essentially a rather glum college/football (I’m not sure any college movie of the era isn’t about football) drama with songs. It is, I suppose, conceivable that pummeling Jack Oakie receives during his fraternity initiation is intended to be funny. However, I cannot imagine anyone—except possibly Eli Roth—finding it so. It’s simply a combination of humiliation and outright sadism, which is apparently an effective bonding tool.

The bonding works very well, though. There are several moments in the film where it clearly looks like Oakie and Arlen ought to get a room. Given the very pre-code tone of the film, that may or may not be intentional. Other pre-code outcroppings occur in the song “Down the Old Ox Road” (depending on where we are in the lyrics, “the old ox road” is either any make-out spot, or slang for a girl putting out). Then there’s the business of Joe Sawyer leaving school three weeks from graduation to get married. When we see him in the next year or so, he has two nearly toddler-sized babies. Nothing is made of this, mind you, but nothing is made of so many things in College Humor that it’s hardly surprising. In her first of three rounds as Bing’s love interest, the generally vapid Mary Carlisle, has a little more personality than she usually exhibits. That she’s playing a fairly unlikable character is another matter.

George Burns and Gracie Allen have been shoehorned into the material and are given a brief song, but little else. The best thing about the movie—other than its undeniable curio value—are the songs. “Down the Old Ox Road” is actually one of the more ambitiously staged numbers in any Bing Crosby picture. Crosby’s trademark laid-back style didn’t lend itself to big production numbers—which were not something Paramount tended toward anyway—and, in fact, he’s offscreen for most of “Down the Old Ox Road’s” length. The number is often discussed as being ersatz Busby Berkeley, but I question that, since it’s very much in the style of a number of cleverly constructed musical scenes held together with rhyming dialogue that were common at Paramount before Berkeley’s breakthrough 42nd Street (1933).

Much better is Norman Taurog’s We’re Not Dressing (1934). The songs are good—a couple of them are great—and the story (cribbed without credit from J.M. Barrie’s 1902 play The Admirable Crichton) is certainly more solid and funnier than the one in College Humor. It deals with a society girl (Carole Lombard)—the kind of girl described by the screenwriters in Bella and Samuel Spewack’s play Boy Meets Girl as “a high-handed, rich bitch”—sailing on her yacht with her wealthy uncle (Leon Errol), his gal pal (Ethel Merman), two effete fortune hunters (Ray Milland and Jay Henry), and a pet bear named Droopy. Also on board—and in charge of Droopy—is Bing as a sailor. Bing and Carole clearly have a thing for each other, but class distinction gets in the way—at least till there’s a shipwreck and the tables are turned because Bing is the only one with a clue how to survive on a desert island.

The real draw here is probably the proliferation of songs—College Humor was not generous with the tunes—but the story works well enough. I’ve read a fair amount of criticism that the story is silly (granted), that it doesn’t make sense (that I don’t get), and that aspects of the film don’t advance the plot (do they realize this is a personality-based musical comedy?). Maybe I’m a sucker for Crosby and a roller-skating bear (OK, so it’s obviously a small person in a bear suit when it’s on skates), but I have very little complaint here. In the realm of this kind of movie, I’m fine with discovering that Burns and Allen are a pair of naturalists living on the supposedly deserted island. It helps that here, they’re given some decent material this time.

Having Ethel Merman (given more to do than in most of her 1930s movie appearances) and Leon Errol is also a bonus. What is less of a bonus than might be thought is Carole Lombard. She’s pretty—sometimes almost luminous—but she only has one really good scene (where she tries not to charmed by Bing singing—at least when he’s looking) and a few scattered moments. However, it needs to be remembered that this is before her performance opposite John Barrymore in Howard Hawks’ Twentieth Century (1934). That would be her next picture, but it’s the film where Barrymore taught her comic timing and how to really let go. If the order had been reversed, We’re Not Dressing might hold a very different position in her filmography.

Still, it’s a fun little picture with its share of surprises—not the least of which is the extent to which Droopy is played by a real bear. The scene where Bing grooms her while singing “She Reminds Me of You” is especially interesting, since Droopy isn’t exactly cooperative. But she must have been an incredibly sweet-tempered animal, since Bing seems more amused than concerned by her recalcitrance. However, the big moment—musically—is “May I?” This isn’t only one of his best songs, but his performance of it for the film is probably the hottest vocalizing her ever did in the movies. Oddly, the commercial recording is only a pale copy of what he does in the film.

The obscurity in the set is Frank Tuttle’s Here Is My Heart (1934) —a somewhat grisly sounding title that would be at home on an ‘80s slasher picture. Apparently, this film was considered lost for years until Bing’s widow, Kathryn Crosby, found a copy stashed away around 1990. That would account for me never seeing it. Back in the early 1970s—when TV stations weren’t controlled by corporations—a Crosby enthusiast at Channel 9 in Orlando, Florida decided to run every movie Bing ever made (albeit, often trimmed for commercial breaks) over a period of weeks. This remake of The Grand Duchess and the Waiter (1926) was not among the films.

The concept involving deposed White Russians living in exile and poverty was probably dusted off owing to the popularity of the Broadway show Roberta, which dealt with the same subject. (Then, as now, Hollywood was quick to emulate any success that came alone.) This one has been reworked to make Bing a wealthy crooner named J. (for Jasper) Paul Jones, who has a laundry list of things he promised himself—when he was 14—he’d do after he’d made his first million dollars. One of the things on that list is to present a pair of dueling pistols that once belonged to the historical (no relation) John Paul Jones to the Naval College at Annapolis. He has one of the pistols. The other apparently belongs to the Princess Alexandra (Kitty Carlisle) in Monte Carlo, living beyond her means with a group of royal relatives (Roland Young, Alison Skipworth, Reginald Owen).

What should be a simple matter falls prey to musical comedy plotting with Bing mistaken for a waiter by the Princess and company—a mistake he doesn’t correct, because he’s immediately smitten with her. In fact, he buys the hotel so that he can continue the masquerade, be near her, and help her out—without her knowledge, of course. It’s silly stuff, but it goes down well in the hands of the cast, and isn’t at all hurt by the inclusion of two soon-to-be hits, “Love Is Just Around the Corner” and “June in January.” The film marked Bing’s second and final teaming with Kitty Carlisle, who was perfect for the role, but not a wholly comfortable screen partner for Crosby. In fact, he seems much more comfortable with Marian Mansfield, who he throws over for Carlisle.

Here Is My Heart is a pleasant, glossy film with the typical sheen of sophistication that was Paramount’s trademark in the 1930s. It isn’t, however, one of underrated director Frank Tuttle’s best Crosby films, especially compared to The Big Broadcast and Waikiki Wedding. But it’s still nice to have around and the supporting cast is first rate. The always-welcome Roland Young is particularly good here as the most unscrupulous (charmingly unscrupulous) of the Russians, and he and Crosby work well together.

A. Edward Sutherland’s Mississippi affords Crosby top billing and a few good Rodgers and Hart songs—“Soon,” “Down by the River,” and, especially “It’s Easy to Remember (And So Hard to Forget)” became Crosby staples—but, let’s face it, so far as history is concerned this is a W.C. Fields picture. Or at best, it’s the W.C. Fields movie with Bing in it. That’s not to say that Bing is bad in Mississippi. He isn’t. He’s actually very good and he teams nicely with Fields. It’s just that it doesn’t feel like his movie. Plus, if he’s not with Fields or singing, the storyline he’s involved in is simply not that interesting, and it’s hard not to wish the movie would get back to Fields sipping an endless procession of mint juleps, cheating at cards or telling tall tales about his days as an Indian fighter.

The film is overall a very nicely judged slice of Old South/showboat Americana. Fields makes a very believable showboat impresario and riverboat captain. Crosby is perfectly fine as the “yankee” who doesn’t subscribe to the Southern concept of shooting people over “affairs of honor,” which is how he ends up on Fields’ boat. His wedding to Gail Patrick is called off and he’s summarily tossed out by his guardian when he refuses to fight a duel. Of course, there’s a younger sister (played by actually slightly older Joan Bennett), who really loves him, but is “just a kid.” She grows up over the course of the film—and Bing grows a very unwise mustache—and, after some misunderstandings, ends up with him. It’s a pretty terrific movie, but it’s just not a Crosby vehicle.

Less likable altogether is the preposterous mish-mash called Sing You Sinners (1938), which uses the famous title song under the opening credits and then forgets about it altogether. The film was produced and directed by Paramount contract director Wesley Ruggles (brother of Paramount comedian Charlie Ruggles), who made College Humor. Ruggles’ name festoons a number of good movies, most of which appear to be good more in-spite-of than because-of Ruggles. This one, however, seems to be not-so-good because of him. The story’s not much, that’s true, but as producer, that burden falls somewhat on Ruggles.

The film—which asks us to believe that Bing, Fred MacMurray and young Donald O’Connor are the sons of Elizabeth Patterson—can’t seem to decide whether it’s a comedy or a drama. It hardly matters, though, because it’s not very good at being either. The problem is that the two main characters aren’t very likable. Crosby’s Joe Beebe is the happy-go-lucky irresponsible brother. That might be fine, but his antics always threaten to ruin other people’s lives. MacMurray plays responsible David Beebe like a man with a stick up his butt, except in the musical numbers. The narrative drags us through a variety of events without much rhyme or reason until it finally decides to become a racetrack drama—complete with O’Connor as the boy jockey.

The highlights of the film are the songs, especially “Pocketful of Dreams” and “Small Fry.” The latter is bizarrely staged as a blackface number—except that nobody is actually in blackface. Crosby, MacMurray and O’Connor merely adopt “black mannerisms.” It’s somehow more disconcerting than actual blackface would have been. It is, however, your only chance to see Fred MacMurray in drag—and he comes across disturbingly like the role model for Tyler Perry.

As Universal has done in other sets (most notably their Marlene Dietrich collection), the final film jumps ahead to an entirely different era, closing out the titles with Elliott Nugent’s Welcome Stranger from 1947. In this case, however, it’s a leap that’s worth making, since Welcome Stranger is one of Bing’s most-likable and least-revived movies. In essence, it’s a secular variation on Leo McCarey’s Going My Way (1944), reuniting Crosby and co-star Barry Fitzgerald—only this round they’re doctors rather than priests. This has the advantage of allowing Bing to have a romance—with Joan Caulfield.

Welcome Stranger adheres pretty closely to its model. It’s not just that Bing and Barry are at loggerheads in a kind of generation gap once again. No, the film even duplicates the template of the earlier film—the extent of creating a charming bedside conversation between the stars. Interestingly, the scene is actually a sly spoof of the original when it turns out that Fitzgerald is trying to manipulate Crosby with an utterly fabricated yarn about a lost love.

In some ways, this may be the more interesting of the two movies. Elliott Nugent may lack the masterful touch of Leo McCarey, but he does a splendid job of capturing the film’s New England setting. It may be—certainly is—Maine as created in the Paramount studio and back lot, but it feels authentic, and Nugent gets the maximum out of the sets. Taking a page from Preston Sturges, Nugent’s camera follows his characters through the town in long takes, not only giving the town a sense of reality, but firmly placing the players in the environment.

Bing gets four nice Johnny Burke-Jimmy Van Heusen songs—“Smile Right Back at the Sun,” “Country Style,” “My Heart Is a Hobo,” “As Long As I’m Dreaming”—and the film does nicely by them. (A fifth song, “Smack in the Middle of Maine,” is always listed—and seems to have appeared on a long out-of-print Crosby compilation album—but isn’t in the film, and was probably cut before release.) After Bing sings “As Long As I’m Dreaming,” one of the locals remarks that he’s “as good as Frank Sinatra.” Interestingly—especially in a film that’s generally realistic—that’s only one of several in-jokes throughout the picture. There’s the obligatory jab at Bob Hope and at least three gags about Bing’s taste for gaudy clothes in really loud colors (a real-life aspect brought on by color blindness). What’s remarkable is that none of this undermines the movie’s believability on its own Hollywood terms.

No, this isn’t anything like an “ultimate” collection. I still want the movies it doesn’t include—especially The Big Broadcast, Anything Goes (1936), and Dr. Rhythm (1938). But it’s a nice step in the right direction. And, for those who don’t know Crosby’s films, it’s a pretty good place to start.

(At the same time, he wrong-headedly preferred—oh, my, no—Frank Sinatra.)

You shoulda listened to your pop, kid.

Naw. He was wrong and so are you. You are young and may yet see the error of your ways. My father hasn’t that luxury.

Pfui.

You’re far too thin for Nero Wolfe.

You’re far too thin for Nero Wolfe.

Jeremy could be Nero Wolfe when he lost a lot of weight and altered his appearance in order to defeat Arnold Zeck.

Oh, and Bing over Sinatra. Without question.

Jeremy could be Nero Wolfe when he lost a lot of weight and altered his appearance in order to defeat Arnold Zeck.

The strain of that might account for this lapse of reasoning, too.

Oh, and Bing over Sinatra. Without question.

Making you listen to Waikiki Wedding all those years ago wasn’t in vain.

Sounds like a good set, but why are they so reluctant to put Big Broadcast out? Perhaps they are working on a whole box set of Big Broadcast movies with the 1932, 36, 37, and 38 outings all in a set?

Is Top O’ the Morning out on any set?

It’s hard to understand the reasoning. A box set? Maybe, but 1938 has already been put out as a Bob Hope picture and in the UK as a W.C. Fields one (I’m betting it’ll show up in the third set of Fields pictures over here, assuming there is one).

I don’t think Top o’ the Morning has ever had any kind of commercial release. The only time I saw it was a bootleg that may have been taken off AMC back when AMC still mattered. It may have copyright peculiarities like some of those other Bing and/or Bob self-produced titles. It’s also right on the edge as to whether it would be owned by Universal or Paramount.