Probably no genre of filmmaking is so generally disdained as the biopic. It’s actually less the films themselves than it is their often somewhat-to-extemely dubious veracity. I would not deny this aspect of the movie versions of the lives of the great. It’s certainly there, though most times I’d argue that it’s no worse than your average high school history book, especially as concerns older biopics where anything too disturbing tends to be given as fine a coat of whitewash as Aunt Polly’s fence ever saw. But it seems to me that even these films served a function in terms of general knowledge that was not without its value.

Looking back over my formative years, I realize what a very large part even the creakiest of these movies played in my conscious knowledge of the existence and basic—very basic—of several historical figures. Indeed, quite a few of them I never came across in the course of formal education, which isn’t that surprising since many would never be encountered except in relatively specialized courses, not in general history ones.

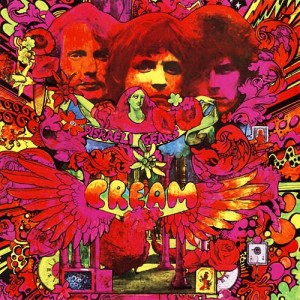

It could be argued that I may have labored under the delusion that nearly every great figure in history looked like George Arliss or Paul Muni wearing various beards or character make-ups, but I wasn’t quite that credulous—and I at least had some clue as to the existence of such folks as Benjamin Disraeli, Nathan Rothschild, Cardinal Richelieu, Emile Zola, and Benito Juarez. And if I otherwise was content to believe that Benvenuto Cellini looked like Fredric March and that both Paul Ehrlich and Paul Julius Reuter bore an uncanny resemblance to Edward G. Robinson, what of it? I am reasonably sure that it was more than many of my contemporaries knew. I know I explained the name of Cream’s Disraeli Gears album and the presence of peacocks on the cover of it to more than a few of my friends.

Of course, all these movies were old at the time I saw them. The most recent of the ones I referenced above was A Dispatch from Reuters from 1940, but because of it I knew how to pronounce Reuters and had some notion of that parenthetical—“(Reuters)”—that cropped up in newspapers—as well as a dramatized, simplified, and canned version of its origins. And I’m grateful to the movies for these sketchy introductions.

I think the first one I saw was also the oldest of the lot, Disraeli (1929), which also introduced me to George Arliss and started a fascination with early sound movies that continues to this day. I can also note that it remains an invaluable example of 19th century acting technique, but all these are side issues to the film as history. As with most of Arliss’ biopics, Disraeli is less an attempt at a history lesson than an historical romp, in this case focusing on the stretch in his life as prime minister of England when he engineered the purchase of the Suez Canal for England. It’s more or less true, but whether it really involved outwitting Russian spies and bringing together two young lovers is another matter. Those elements, however, made for entertaining drama. It also—and this is a major point for me—drove at least one 14-year-old to buy a pretty weighty—about 800 pages—biography on the real Disraeli.

In much the same way, The Affairs of Cellini (1934)—a film which presented the life of 16th century artist and artisan Benvenuto Cellini as bedroom farce—caused me to seek out Cellini’s autobiography. One day I may make it through that one, but I’m not laying money on it. Somehow the book didn’t capture Fredric March’s amusing portrayal of the man, nor did it appear that it was going to present his life as a game of high-toned woman-swapping between Cellini and the Duke of Florence (Frank Morgan). Oh, well. It’s actually a little alarming to consider the prospect of an audience thinking this was in any way historically sound.

On the other hand, The Life of Emile Zola (1937)—in which Paul Muni impersonated the French author and presented him as a tireless crusader of justice thanks to the Dreyfus affair—offered some interesting scope. In the first place, it made me the only person in my circle who got the “Dreyfus was guilty” joke in Costa-Gavras’ Z (1969)—something that made me feel very worldly, I can tell you. But more, it afforded me the ability to make a pretty rarefied choice when called upon in a high school French class to do a book report on a French novel. I’m not at all sure that my teacher actually approved of my choice of Zola’s Nana—a book about a prostitute—but it was certainly a more knowledgeable choice than many. (One person, who shall go unnamed, picked Louis L’Amour’s Hondo, despite my telling her that I didn’t think it was actually a French novel by any possible definition.)

The interesting thing is that at the time these movies were made, they were considered prestigious and important—and the acting in them was the last word in actorliness. That last has more to do with changing tastes in acting styles, but otherwise, it’s the fact that not only do these movies—and others like them—seem quaint in their sanitized or trivialized life stories, but they ushered in the truly corny and absurd biopics that came along in their wake. A case can, of course, be made that an unintentionally funny film like Charles Vidor’s A Song to Remember (1945) opened up the music of Frederic Chopin to a new audience, it’s impossible to overlook what a truly bad movie it is. And Cole Porter was hardly in need of convert fans when Cary Grant impersonated Cole Porter in Night and Day (1946), but a biopic of Porter that didn’t—and couldn’t—deal with his homosexuality is no biopic at all.

In some ways, it’s a case of getting out of a thing what you put into it, sure. I mean these experiences would have gone nowhere if the movies didn’t intrigue me sufficiently to go beyond the movies themselves—much like reading a novel after seeing the film that was based on it. That wasn’t invariably the case, of course. I wasn’t so taken with Juarez (1939) that I pursued any study of Benito Juarez, but at least faced with a Jeopardy-level clue like, “He was known as the Abraham Lincoln of Mexico,” I’d be ready with, “Who was Benito Juarez.” This probably won’t come in useful, but you never know.

I’m trying to think what the last biopic was that I saw. The last serious specialist in the field was Ken Russell, whose last full-blown theatrical biopic was Valentino back in 1977, though a case can be made for biographical elements in his Gothic (1986) and Salome’s Last Dance (1988). of his biographical film work after Valentino has been done for British TV. Several filmmakers, of course, made the occasional biopic—traditional and otherwise—in more recent times, but the last titles that occur to me are Irwin Winkler’s take on Cole Porter, De-Lovely (2004), Scorsese’s film on Howard Hughes, The Aviator (2005), and Oliver Stone’s W. (2008).

I may be forgetting something, but all in all, it seems that the biopic has given way to the “based on true events” sub-genre. Now, that has produced some very estimable recent films like The King’s Speech and 127 Hours, but it’s also given us Secretariat, Conviction, Casino Jack, and, God forbid, The Rite. One of the drawbacks to the “true story” approach is that they’re all too often a hybrid of the “ripped from the headlines” drama and the biopic—and one that frequently smacks more of scanning the tabloids in a grocery store check-out line than anything else.

What I find troubling about this—apart from an inordinately high number of viewers who seem unable to separate the idea of “based on a true story” and the literal “truth”—is that, apart from The King’s Speech, these films have little or no historical perspective. Oh, I’m not arguing that movies require some kind of educational component, but it’s interesting that audiences from 70-plus years ago were considered capable of being intrigued by and care about shadowy figures from history, but today they’re generally not. Yet we’re supposed to be so much more sophisticated, aren’t we?

Today’s (3/6) HFS showing of REMBRANDT drew a larger than usual crowd. Younger members of the audience were impressed with the “craftsmanship of the film” to quote one and Charles Laughton’s ability to “say his lines like poetry” to quote another. Someone even knew who Gertrude Lawrence was (and no they hadn’t seen STAR).

Younger members of the audience were impressed with the “craftsmanship of the film” to quote one and Charles Laughton’s ability to “say his lines like poetry” to quote another.

The need to see his Dr. Moreau for real poetry!

Someone even knew who Gertrude Lawrence was (and no they hadn’t seen STAR).

It’s unfortunate that her role in Rembrandt gives no hint of what made her great.

(One person, who shall go unnamed, picked Louis L’Amour’s Hondo, despite my telling her that I didn’t think it was actually a French novel by any possible definition.)

And to think, now she’s a PhD! Actually, I think she was aware of her subterfuge even before your enlightenment.

And to think, now she’s a PhD! Actually, I think she was aware of her subterfuge even before your enlightenment.

That may well be. My stated skepticism came late in the day. It may also be that the decision was based on the book being in the house. I’m not sure. I know that Mme. Kirkland was not bamboozled, but she did let it slide, if memory serves.

..but it’s interesting that audiences from 70-plus years ago were considered capable of being intrigued by and care about shadowy figures from history, but today they’re generally not.

Heh heh. I’d suspect that that problem has more to do with a dearth of competent script writing and film making than a supposedly unsophisticated audience. But that’s just me.

As an amateur student of history I think that Hollywood misses the boat by “embellishing” historical figures. I’ve found that studying people like, oh say Gen Custer, reveals that the real Custer was far more interesting (and rotten) than any of the films that depicted him. I’d bet that a smarter person than me could write an “off the hook good” screenplay by sticking mainly with the facts and avoiding the tendency towards demonization or hagiography.

Another figure, George Washington, has been built into a figure that is unrecognizable from the real man. Yet the real GW was in his own way an even greater person than the demigod that has been Hollywood’s invention. But I guess it would take a lot more work than just sticking to tropes.

Another figure, George Washington, has been built into a figure that is unrecognizable from the real man. Yet the real GW was in his own way an even greater person than the demigod that has been Hollywood’s invention.

I don’t think Hollywood has tackled Washington — apart from a TV movie — except as a side issue. And I’m not sure that Hollywood is the culprit anyway. I think it goes back to history books that were carefully designed not to frighten the horses and the parents of schoolchildren.

Secretariat counts as a biopic if you assume that the subject need not be human.

I tend to think the more effective ones (if you can call them biopics and not something else) pick a defining moment and focus on that, like The King’s Speech, or Thirteen Days. Otherwise, you invariably get a whole lot of onscreen dates, disconnected vignettes, and varying degrees of usually less-than-convincing age makeup.

Fake biopics are the toughest, judging by Forrest Gump and Benjamin Button, both (IMO) inexplicably beloved.

The best biopic I’ve seen recently was the HBO movie Temple Grandin. If it had been released in theaters, I doubt Natalie Portman would have an Oscar right now.

I think the THE KINGS SPEECH model is far preferrable to a standard biopic format, which tries to squeeze a whole life into 90 minutes and ends up with a lot of movies that feel like the same movie. A person’s life doesn’t naturally fit into a 3 act structure, and this seems to lead to some kind of mad-libs biopic structure into which new names are placed.

This is especially true of music biopics. NOWHERE BOY and BACKBEAT work great because they pick a small moment from their subjects lives that actually plays like a story with a beginning, middle and end rather than playing like an illustrated Greatest Hits album (see RAY, WALK THE LINE).

Thanks for this focus!! I have enjoyed remembering some films like, GOOD LUCK AND GOOD NIGHT and ED WOOD…not really favorites, but enjoyable at the time. And several sports movie figures….

And just for the record…Mme Kirkland’s response was, “I have given you an A for a well-written report, but I think we both know that Louis L’Amour is no more French than you or me.” In a fit of confession, about thirty years later, I located her in her flower shop where, no doubt she retired in order not to have to teach French to such as moi. I wanted her to know that I finally actually read Les Miserables by Voltaire which was the original intention. No doubt had there been such a thing as DVD rentals, someone would have pointed the way to Les Mis the night before and Louis L’Amour would never have come into the picture at all.

Secretariat counts as a biopic if you assume that the subject need not be human.

I kinda do assume that, but then I loathed Secretariat. Come to think of it, I wasn’t fond of Seabiscuit either.

Fake biopics are the toughest, judging by Forrest Gump and Benjamin Button, both (IMO) inexplicably beloved.

Inexplicable is the word for it. More appalling is the number of people who think these are real people.

I think the THE KINGS SPEECH model is far preferrable to a standard biopic format, which tries to squeeze a whole life into 90 minutes and ends up with a lot of movies that feel like the same movie.

Most biopics tend to focus on one event really, i.e., Disraeli and purchase of Suez Canal, The Life of Emile Zola and the Dreyfus case.

But I’m not really arguing for the quality of the films. I’m arguing for the value of the existence of such films in terms of some kind of basic knowledge.

And several sports movie figures….

I can’t think of any of those I’ve actually watched.

In a fit of confession, about thirty years later, I located her in her flower shop where, no doubt she retired in order not to have to teach French to such as moi.

My dear, what a capacity for guilt you have!

I finally actually read Les Miserables by Voltaire.

Now, I’m reasonably sure you know that’s not who wrote Les Miserables.