This is far and away the hardest thing I’ve ever had to write. The very idea that Ken Russell could be dead is unthinkable to me. This isn’t just the passing of one of the—not always fully appreciated—true giants of cinema. This is the passing of a friend of nearly 30 years—a man I unreservedly loved. The very fact that I am—for the very first time—writing something that he will not be reading is strange and saddening in itself. And that makes this even harder, making various regrets snowball into something almost paralyzing.

When Lisi Russell called me Sunday evening I could tell by her voice that it wasn’t good news, but I really wasn’t prepared to hear, “We lost him this afternoon.” It was a call I’d been dreading for a while, but never actually expecting. There was just something about Ken Russell—or T’other Ken as we called him to save confusion—that was so much larger than life that he seemed indestructible. But he wasn’t. And after staying up late the night before and watching Donnie Darko (Lisi said he liked the rabbit), he took a nap Sunday afternoon and—just didn’t wake up.

After I gathered myself, the first thing I thought of—and close to the first thing I said—was that I’d so wanted him to see Hugo. Well, it was true. Here was a visually stunning movie with silent movies, kids, fantasy, and trains—and anyone who knew Ken or knows his work knows how he felt about trains. If it had had a white horse in it and more fire, it might have been a movie that Martin Scorsese had made just for Ken. As it was, it was close. I guess my respone was not so odd, since it’s impossible to think of Ken and not think of movies and vice versa.

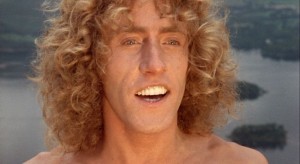

Of course, the movies are how I discovered Ken Russell. In the summer of 1975, I saw Tommy and neither my world, nor I would ever be the same. (The poster claim that “Your senses will never be the same” might have been addressed directly to me.) I was then 20. I hadn’t realized it, but I’d been looking for Ken Russell for a very long time. Oh, I’m not saying that I hadn’t had revelatory moments earlier—and I’d continue to have them (just had one on Friday, in fact)—but this was different. There was an immediate connection. This man spoke to me as no one else ever had. And my subsequent exposures to his films only reinforced that. If you’d told me at the time that I would come to know Ken Russell personally and actually become a friend, I’d have said you were crazy. (In 2005 when Barry Sandler and I were presenting Ken with a Lifetime Achievement Award at the Asheville Film Festival, I said as much—and Ken, being Ken, said, “And you’ d have been right!”)

By 1981 I’d determined that I had to write a book about Ken’s films. (Actually, my friend Bobby Pohle pushed me into it—I think in an attempt to get me to stop talking about the movies, which didn’t work, as you’ve perhaps noticed.) Through a very circuitous series of events—too long to detail here—I ended up in contact with Ken, who agreed to answer one set—“and one set only”—of questions. Well, he must’ve liked those questions, because next thing I knew he was offering me stills for the book and we’d entered into a correspondence. The book—Ken Russell’s Films—came out in 1984. The correspondence, phone calls, and occasional meetings lasted till this past Sunday. And the world turned a little colder and a lot less interesting.

It’s odd that Ken would leave this world on the 27th. In his mind, 27 was his lucky number. I’m not sure why, except that he was born in 1927. Whatever the reason, you might note that the number occasionally crops up in this films. The train in the early scenes in Tommy is emblazoned with “75027.” (Yeah, I’ve seen this movie a few times.) Maybe—if you’re at all fanciful—some part of him chose the 27th as a departure date.

I’ve watched the tributes pour in over the past few days. I’ve listened to Glenda Jackson give the British film industry a well-deserved blasting for their treatment of Ken Russell (“I think that’s one of the scandals of the last decade—they’ve all pretended that Ken never existed”)—occasionally making a fool of myself by applauding her remarks in my living room. (It perplexed the cats.) I’ve seen the sincere (Michael Winner, Scorsese, Ben Kingsley) and I’ve seen some that looked like people wanting publicity for themselves. I’ve seen the tabloid trash from Britain’s Daily Mail (and suspect I know its major source). I’ve also seen the critic from The Hollywood Reporter use the occasion to do an apparently grudge-based hatchet piece. I guess it was all to be expected—Ken was never a stranger to controversy and he made some enemies (sometimes unnecessarily). I also suspect it’s not over. And I suspect it doesn’t matter in the long run.

What matters—at least to the world at large—is this incredible body of work that stretches from the amateur film Peepshow in 1956 to Boudica Bites Back made with students at Swansea Metropolitan University in Wales in 2007-2008. If you go back to Peepshow—which is available in multiple parts on YouTube—it’s almost shocking to find how formed Ken’s grasp of cinema was at that time. Even more surprising is how the film is edited—no one (with the possible exception of Michael Powell) was editing like that in 1956.

But then, it’s not so shocking since the movies had been his most constant companion since childhood. While Ken’s autobiography—called A British Picture in the UK and Altered States here—is not the last word in veracity (he once told me it was true “in spirit”), several things can be gleaned between its fanciful covers. One of these is the image of Ken as a rather solitary child. There are no references to playing with other children and no mention at all of playing with his brother, Ray.

His 1989 TV film of the book, A British Picture: Portrait of an Enfant Terrible reinforces this. In fact, it goes further with Ken referring to his silent movie collection this way: “My home movie projector was little more than a hand-cranked magic lantern, but to me it was truly magic, for you could conjure up your friends whenever you felt like it.” His childhood friends were Felix the Cat, Betty Boop, and Charlie Chaplin. I don’t think it was intentional, but the portrait is that of a lonely child. There’s an irony here, since Ken falls prey to the basics of the way he approached other artists in his biographical films—telling you more in his art than he intended. Mixed in with the embellishments and even outright fabrications of A British Picture there’s a good bit that is more than true “in spirit.”

One of the key things to understanding Ken and his work, I truly believe is found in stories he told from time to time—including in the book—about his cousin Marion, to whom he dedicted his 1989 film The Rainbow. She is the only person I ever recall him mentioning in terms of a childhood friend and he devotes several pages to her in his book. He was, I think, in love with her and I don’t think he ever completely got over that—or over her peculiar and inexplicable death during WW II.

Marion had been out walking by herself and for reasons no one knows she left the footpath, crawled through a barbed wire barrier and into a mined field (put there by the army against a possible German invasion) where she met her end. This profoundly shook the young Ken and it seems to have been haunted by it for the rest of his life. For that matter, it’s hard not to view Ken’s own professional life as that of a man deliberately walking through a metaphorical minefield in his career. Each new step was a risk, and while that way disaster lurks, so does the possibility of greatness.

These memories of childhood seep into all his movies—that sense of loneliness and impending disaster insinuates itself into everything. It’s even present in his lightest works. There are undercurrents of an ineffable sadness in movies like French Dressing and The Boy Friend. For a filmmaker as prone to a sense of playfulness as Ken was, he seems to have been incapable of escaping a certain sense of melancholy, which imbues his work with a feeling that is unlike anyone else’s.

I don’t mean to suggest that Ken’s work was ever really negative—and it certainly wasn’t downbeat. In fact, it was the positive in Ken’s films that drew me to them as much as anything. No matter how dark his films were—and there are few movies darker than The Music Lovers and The Devils—they were always ultimately about redemption and transcendence. That for me was the hook—not the much publicized excesses or outrages, though those too were a major part of it. Going through Ken’s filmography reminds me John Lennon’s story of climbing a ladder at the art show where he met Yoko. At the top of the ladder there was a magnifying glass that you used to read a tiny word on the ceiling—“Yes.” Ken’s films are the same—a climb to that “Yes.”

Now, it may be argued that a lot of my take is grounded in the fact that Tommy is the film I saw first. And that can be compounded by being followed in a few months by Lisztomania. It’s certainly true that those two films are perhaps the best example of that mindset. Tommy, in fact, is the clearest expression of the idea of redemption and transcendence on a grand scale—and it actually ends with the triimphant climb to a cosmic “yes.” (The other night Lisi pointed out that in reality Tommy is Ken’s own story—and she’s right.) Lisztomania with its loopy happiest-ever-after-ending cements it. That much admitted, it’s fair to add that I did see The Devils between the two, but even there, I sensed that it was ultimately a movie about Urbain Grandier’s (Oliver Reed) transcendence. Ken himself once described it as “the story of a sinner who becomes a saint.”

More, let’s flash forward to Ken’s final theatrical feature, Whore from 1991. This low-budget, bitterly—sometimes blasphemously—funny film is by no means one of his sunnier works. Of course, any movie that has a hooker (Theresa Russell) and a street hustler (a delightful Antonio Vargas) while away an afternoon in a movie house watching Disney’s Fantasia (a joke conveyed only by the soundtrack using recordings of the Beethoven Sixth and Mussorgsky’s “Night on Bald Mountain”) is in pretty good humor on some level. But the real point is conveyed in the final shot of the hooker walking up out of a subterranean parking garage into the sunlight. In the context of the film, it can hardly be called a moment of redemption or transcendence, but it offers the character the possibility of those things.

Let’s put it this way, I have never come away from a Ken Russell film depressed. That even extends to such films as Women in Love, The Music Lovers, and The Devils, all of which can be reasonably described as shattering in their impact. But shatter is not in my mind the same thing as depressing, though it can certainly—and rightly—leave you in a thoughtful state. There is, however, something in Ken’s films that is somehow hopeful in spite of everything. It may simply be that they are so utterly infused with life. Back in 1975 David Sterritt—then film reviewer for The Christian Science Monitor said that Mahler “throbs with life.” I’d go further and say that’s true of all Ken’s films.

I suspect that’s why I find it hard to believe that Ken himself is no longer with us. Like Eric Fenby (Christopher Gable) in Song of Summer wanting to argue the point with the doctor (Norman James) who has told him that Frederick Delius (Max Adrian) is dying (“Delius is full of life!”), so I want to deny the truth. But I know I can’t. I can only sift through memories and the films, and, yes, that’s a lot.

It’s funny for me to realize that after the beginning of the relationship, Ken and I didn’t talk all that much about his films—except when he was working on a new one or when I was writing about one of them or when we were together at some festival function. We talked about many things over the years—including other people’s films—but his own films we tended to leave to a sense of mutual understanding and the idea that we didn’t need to talk about them.

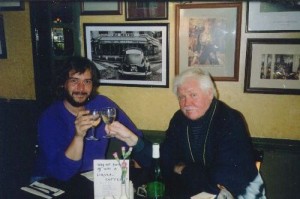

The last time we saw each other was in 2009 at the Florida Film Festival where he was being honored with a showing of Crimes of Passion, after which he did a Q&A with the film’s screenwriter Barry Sandler (pictured above with Lisi, Ken, and myself). It was actually one of the few times where we actually talked about a specific film—Crimes—in any great depth. Still, most of the time we spent together dealt with other things—what he was doing, what I was doing, and sharing a kind of in-joke at the fact that he was so very obviously playing up his supposed outrageous persona for interviewers.

This whole business of Ken being outrageous and outspoken both was and wasn’t well-deserved. The first couple of times I met Ken, I quickly realized that this persona was carefully cultivated as a kind of protection against the world. (No, I’m not saying he couldn’t be outrageous, outspoken, and even difficult, because he most certainly could, though very rarely with me.) The truth was that he was almost painfully shy and somewhat uncertain of how to deal with people. He invited me to come backstage after the 1985 production of his staging of Madame Butterfly and very quickly added, “That is if you’d like to.” The same thing happened when we met later in London, inviting my wife and I to come to lunch—“That is you’d like to.” It never occurred, it seems, to this supposed egomaniac that anybody had in fact come for the specific reason of spending time with him!

Of course, there were occasional exceptions to the lack of conversations about his own movies. Every so often, I’d bring up the cut footage from The Devils—especially “The Rape of Christ” sequence. Invariably, he’d tell me that it was lost, gone forever—and that “it wasn’t so hot anyway.” Amusingly, once this never-to-be-found footage that “wasn’t so hot anyway” was found, it turned into “one of the most mind-blowing sequences ever censored.” (And though it’s been shown on TV as part of a documentary on the film—not to mention all the bootleg copies of a “restored” cut—it seems it will continue to be censored, since the footage is not going to be in the film’s finally legitimate DVD release.) But this kind of constant reassessing was part and parcel of Ken Russell.

Over the years, I heard Ken call Tommy, The Devils, Song of Summer, The Debussy Film, and even Lisztomania “the finest thing I’ve ever done.” It seemed to largely be determined by what he’d seen most recently. I understand his plight because—though I’ll always default to Tommy—I find it an impossible choice when all is said and done. However, in the end, he appears to have settled on The Music Lovers as his favorite of all his films. At least, that’s where he was throughout the huge retrospectives in his honor in New York, Los Angeles, and Toronto last year. I have no argument with the choice, though I’m glad I don’t have to limit myself to any single film.

Of all his works, he only ever “disowned” two of them—the 1991 TV film Prisoner of Honor and the never really released Mindbender from 1996. The former isn’t a bad film, but it was taken away from Ken and recut by producer-star Richard Dreyfuss and the overall experience was not a pleasant one. Mindbender, on the other hand, is pretty darn bad. It is, in fact, bad enough that Ken once told his friend Leonard Pollack to please not help me track it down, because he didn’t want me to see it. In all honesty, I never understood why he persisted in liking the 1998 Dogboys that he made for Showtime. I could see more of his fingerprints on Mindbender, but then he told me, “I did it to prove I could make something that wasn’t ‘art,’” and he did. It’s less that it’s bad than it’s simply terminally ordinary—the one thing a Ken Russell film never should be.

Ken could be downright odd about his films on occasion. I could understand his rethinking of his films over the years. It made perfect sense to me when he told me that he no longer sided so much with Ursula’s side of the argument at the end of Women in Love—something the film itself does—and probably wouldn’t end the film on that image of her anymore. But what is one to make of his argument against Ang Lee’s Brokeback Mountain when it became obvious that his problem with it was that it was being hailed as a breakthrough for dealing with gay themes in a movie and he thought it wasn’t a patch on what he’d done in Women in Love. OK, fine, except he’d gone on record stating that after the famous nude wrestling scene between Rupert (Alan Bates) and Gerald (Oliver Reed) Rupert isn’t making a homosexual pass at Gerald. I don’t know what caused the about face on this, but I was mildly amused when Brokeback became all right—as long as I thought Women in Love was better (and I do).

It’s not that Ken wasn’t self-aware. He was—though no more so than anyone. Back in 1992 he made the TV film The Secret Life of Arnold Bax, which he told me while it was in production was “my most personal film yet.” (This is the film Martin Scorsese was talking about that he couldn’t remember the title of.) On the surface, this might seem to refer to the fact that Ken cast himself as the composer of the title—and that Glenda Jackson (in her last acting stint prior to going into Parliament) played Bax’s longtime companion Harriet Cohen. But there was more to it than that, since Ken had long felt a kinship with the neglected composer—to the degree that he produced recordings of some Bax symphonies in the early 1970s when he was (as he put it to me) “flush.”

But it is a moment late in the film that is the most telling thing. Bax has recruited a dancer (Hetty Baynes) to go with him on a weekend holiday to the seaside. The primary goal is less amatory in any direct sense (though it’s obvious that would be all right with Bax) and more to get her to act out a fantasy. He wants to go to the beach with a portable gramophone and have her emerge naked from the sea as the goddess Fand to a recording of his composition “The Garden of Fand.”

First she balks at the nudity and then she balks at his refusal to paricipate in the proceedings by dancing on the shore, telling him flat-out, “You’re all very fond getting other people to do your fantasies, but not so hot when it comes to acting them out yourself.” I can think of no single moment in Ken’s filmography where he’s this confessional. At the same time, this does nothing to keep the image of him sitting on a desolate beach in the winter to just watch the picture he’s carried in his mind come to life—even if in a compromised form. (The compromise in itself makes a comment on the gulf that almost always separates what the artist has in mind and the work that results.)

It’s perhaps best to leave Ken here on the beach for now. I’ve spent far too long wandering through my memories of him and his work—and have only barely scratched the surface. Maybe I’ll do a better job of it when Justin Souther and I turn over the January screening schedule of the Asheville Film Society to Ken’s works (more on this when the titles are set). I don’t know. What he really deserves is the long-proposed follow-up book to my Ken Russell’s Films—something that’s been in the offing for about 13 years, and something I regret did not get done while Ken was alive. I’m not entirely happy with the old book, for one thing. How could I be? It was written between the ages of 26 and 29. I’m a better writer now and my level of understanding has, I hope, deepened. More, there’s so much that he did after that old book.

I spoke of my regrets about the book—titled Nymphomaniacs, Nuns, and Messiahs: The Life and Films of Ken Russell—to Lisi the other night. She tried to assure me that I’d actually already done the book, but that I’d done it in pieces over the past several years in my writings here. I don’t know if I agree with that or not—probably I don’t. She told me how much Ken enjoyed and appreciated those articles and reviews, but always said, “If he keeps this up, people will say we’re in love.” Well, so what? That’s probably not entirely untrue.

I’ll leave it here for the time being with what former Oingo Boingo drummer “Johnny Vatos” posted on my Facebook page—“Now your job really begins, to tell the story forever”—stuck in my head. And I’ll close with the image from the credits of Song of Summer with Ken’s credit superimposed on the image of the sun in eclipse. That’s about as far from the ending of Tommy as you can get, but it rather reflects my current frame of mind.

Wonderful t’other Ken – I am still reading all the ‘tributes’ but yours is certainly from the heart.

Hard to grasp we have no more Ken Russell. But, I guess we have his work to enjoy for the rest of our days.

Thanks ?

Barry

Fabulous! A beautiful, beautiful tribute to a man whose work inspired me and took me to new roads in my life. God bless Our Ken!

Dan

PS: Look at the cast he has on his hands, now!

Thank you for sharing your thoughts, feelings and experiences regarding Ken Russell. As you know from our conversations over the years, I always admired ALTERED STATES, even with it’s flaws. And I still smile when I think of the imaginary script for Ken Russell’s SANTA CLAUSE we concocted during a late night exchange when we were both supposed to be working on other writing projects.

I hope you do get around to writing the Ken Russell book that is still so sorely absent in this world. You’re certainly the only writer who can do it the way Ken would’ve liked.

Michael

A wonderful, thoughtful, positively beautiful piece. Ken meant the world to many of us, and your essay has given me great comfort in the shadow of his passing. I look forward to your second book on his work, whenever it may come. Cheers.

I hope the publicity surrounding his passing leads people to seek out his work, especially now that THE DEVILS is finally getting a proper release – although a compromised one.

Do you think TCM will do some sort of tribute marathon?

You should have delivered his eulogy. I’ve read every word on him that I could find since I first saw the terrible news on Monday morning. Nothing else is so eloquent, or personal.

Write your second book. I’m off to watch Litzomania in a bit.

But, I guess we have his work to enjoy for the rest of our days.

This is true, though from a personal standpoint it’s not as comforting as it might be. It would also be more comforting if more of his work was readily available than it is.

Fabulous! A beautiful, beautiful tribute to a man whose work inspired me and took me to new roads in my life. God bless Our Ken!

Thanks, Dan.

Look at the cast he has on his hands, now!

I admit I do like to toy with that idea — Ken back together with Ollie and Max Adrian and Christopher Gable and Imogen Claire and Alan Bates and Graham Armitage and…well, you get the idea.

I still smile when I think of the imaginary script for Ken Russell’s SANTA CLAUSE we concocted during a late night exchange when we were both supposed to be working on other writing projects.

Time well spent!

A wonderful, thoughtful, positively beautiful piece. Ken meant the world to many of us, and your essay has given me great comfort in the shadow of his passing.

Thanks, Mitch.

I hope the publicity surrounding his passing leads people to seek out his work, especially now that THE DEVILS is finally getting a proper release – although a compromised one.

I’m just glad that a rediscovery of his work — maybe in part because of those of us who’d kept telling the world how great it is — actually started before he died. But isn’t it a sad commentary that I was contacted to provide copies of quite a few of the TV titles for some of those retrospectives? These things ought to be better available than that.

You have no idea how painful it was to see the same story of neglect with a different filmmaker played out in that second viewing of Hugo today.

Do you think TCM will do some sort of tribute marathon?

Even though they have access (I’m pretty sure) to Billion Dollar Brain, The Devils (yeah, they’ll show that!), The Boy Friend, Savage Messiah, Lisztomania, and Altered States, I’m not expecting it. But I’m sure to hear if they do anything.

You should have delivered his eulogy.

Christ, Arlene, I wouldn’t have been able to get through it without breaking down. I almost lost it in 2005 just presenting him with an award!

I can totally understand. But it would have have been a fitting one.

http://www.thedailymash.co.uk/news/arts-&-entertainment/ken-russell-funeral-banned-by-the-bbfc-201111294604/

A college friend took me to see LAIR OF THE WHITE WORM at a nearby theater, and after those hallucination sequences, I was hooked. Thanks to video stores in the 80s, Russell was the first director I sought out during my impressionable years. I was able to watch THE DEVILS, TOMMY, WOMEN IN LOVE, CRIMES OF PASSION, GOTHIC, SALOME’S LAST DANCE and many more.

I don’t think I’d have two video stores if it weren’t for him and that dangerous path he led me down.

I don’t think I’d have two video stores if it weren’t for him and that dangerous path he led me down.

Don’t forget he was aided and abetted by certain chapters in a certain book…

Don’t forget he was aided and abetted by certain chapters in a certain book…

I don’t if I should tell you “thank you” or “f*** you.”

I don’t if I should tell you “thank you” or “f*** you.”

Maybe a bit of both.

I thought it was really interesting to hear Scorsese talking about Russell. I’ve always wondered what Russell thought of Scorsese’s films. Any idea? I think I read somewhere that he liked Taxi Driver.

I thought it was really interesting to hear Scorsese talking about Russell. I’ve always wondered what Russell thought of Scorsese’s films. Any idea?

No. We’d never discussed it, nor have I come across any references to it. I assure we would have discussed it after Hugo, but…

Ken, great post for such a sad event. I have a bookshelf filled with books about Ken and his fine cinematic output and I regularly pull yours out for a browse. It might be time for a reprint. My favs are yours, John Baxter’s Appalling Talent and the recent phallic Frenzy and of course Ken’s own A British Picture.

Chris

It might be time for a reprint.

It needs an update (and a rewrite in some places), not just a reprinting, but thanks for the kind words.

Ken, I’m curious if his passing might finally get Warner Brothers to finally release THE DEVILS in the states. They’ve got some heavy hitters on their lot like Chris Nolan and Clint Eastwood… I wonder if anyone has reached out to them.

First I’ve heard of Eastwood, and who is it you’re wanting “reached out” to? Eastwood and Nolan or WB? Near as I can tell, WB is waiting to see if universes collapse with the UK release to decide whether to let it be brought out Stateside. But bear in mind that WB is still adamant, it seems, over nothing more than the UK print (which is still better than the US print and oceans better than the version that was out on VHS). Don’t be expecting the censored scenes to be in any of these releases — despite the fact that there are thousands of bootlegs of the “Rape of Christ” floating around.

I really don’t know if Eastwood likes The Devils or not. However, he has been with WB for decades now, and surely he has some pull.

I am confounded why they want to keep this particular film in the vaults, and I feel it’s going to take some heavyweights to have it see the light of day.

I really don’t know if Eastwood likes The Devils or not. However, he has been with WB for decades now, and surely he has some pull.

I am confounded why they want to keep this particular film in the vaults, and I feel it’s going to take some heavyweights to help it see the light of day.

I really don’t know if Eastwood likes The Devils or not. However, he has been with WB for decades now, and surely he has some pull.

I am confounded why they want to keep this particular film in the vaults, and I feel it’s going to take some heavyweights to help it see the light of day.

I really don’t know if Eastwood likes The Devils or not. However, he has been with WB for decades now, and surely he has some pull.

I am confounded why they want to keep this particular film in the vaults, and I feel it’s going to take some heavyweights to help it see the light of day.

I really don’t know if Eastwood likes The Devils or not. However, he has been with WB for decades now, and surely he has some pull.

I am confounded why they want to keep this particular film in the vaults, and I feel it’s going to take some heavyweights to help it see the light of day.

I really don’t know if Eastwood likes The Devils or not. However, he has been with WB for decades now, and surely he has some pull.

I am confounded why they want to keep this particular film in the vaults, and I feel it’s going to take some heavyweights to help it see the light of day.

Ah! The website strikes again! Or did you actually post that six times?

I don’t think anything short of a papal decree will get the film out uncut. I don’t think anything other than the BFI release in the UK coming out without public outcry against the film will get even the original 111 min. British version released here.

Say, anybody got any idea why some place hawking Ugg Boots keeps spamming the shit out of this entry?

I hope I made my point!

I’m officially coming out against the new site as well.

I hope I made my point!

I’m officially coming out against the new site as well.

You did!

Ken, a genuinely heartfelt and moving goodbye, embellished with a wonderfully insightful collection of stills. It’s a crime that the Great Man himself will never have the opportunity to read it.

Though, in a way… he already has.

With deepest sympathy,

JMP

It’s a crime that the Great Man himself will never have the opportunity to read it.

Lisi might argue that he has.

And thank you.