Last week the trailer for Guy Ritchie’s Sherlock Holmes (slated for a Christmas Day release) hit theater screens and the internet. For those not following such things, Sherlock Holmes stars Robert Downey, Jr. as Holmes and Jude Law as Dr. Watson. It’s very obviously a rethinking of the much loved Conan Doyle characters. The tone is comedic and the trailer suggests considerably more action than is generally associated with the detecting duo. Not surprisingly, this has caused much consternation among the Sherlockian set.

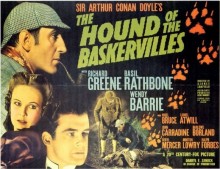

As much as I am not surprised by this, I find myself asking, “Why?” First of all, it’s not as if there’s any actual concensus on just how best the characters are portrayed on film. Anyone driven to the stories themselves by way of the most famous film series—the one starring Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce that ran from 1939 to 1946—is apt to be more than a little surprised to find that Doyle’s Watson bears no resemblance to Bruce’s befuddled comedy approach, not to mention the fact that Holmes’ use of cocaine is limited to exactly one line of dialogues (“Watson, the needle”) said at the end of the first film, The Hound of the Baskervilles.

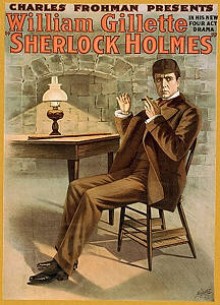

Our images of Holmes are many and varied and are often the result of later changes. For example, the business of Holmes puffing away on a calabash pipe with meerschaum bowl is a later outgrowth that appears (I say “appears” out of fear that a Sherlockian scholar will descend upon me for repeating information gleaned from William Baring-Gould’s The Annotated Sherlock Holmes that by now someone has surely disputed) to have originated with William Gillette onstage. Baring-Gould indicates that Gillette found it easier to speak onstage with a curved (though not necessarily calabash) pipe in his mouth, but that’s the image we generally have of the character because it stuck. I’m not even going to get into the deestalker hat debate.

Similarly, it should be noted that Gillette is also the man who supposedly asked Conan Doyle if the creator of the character minded if he married off Holmes at the end of the play he (Gillette) had written featuring himself as Holmes. Legend has it that Doyle told Gillette, “I don’t care if you kill him.” Since Doyle wasn’t always fond of his creation, I will refrain from suggesting that he had a better perspective on the matter than some of the author’s more enthusiastic enthusiasts.

Holmes and Watson have certainly weathered graver assaults than those suggested in the two-and-a-half minute trailer for Ritchie’s film. The various updatings—Holmes fighting gangsters in William K. Howard’s 1932 film Sherlock Holmes (cinematically one of the better Holmes movies) or battling Nazis in the WWII era Rathbone-Bruce entries—certainly played fast and loose with the characters. (There’s a charming moment in the first of the WWII films, Sherlock Holmes and the Voice of Terror [1942], where Holmes starts to don his deerstalker and Watson stops him by saying, “Holmes, you promised,” as if to announce the forced modernization.)

This is as nothing compared to Paul Morrissey’s The Hound of the Baskervilles (1978) which turns Holmes and Watson into Peter Cook and Dudley Moore. (I note with amusement that the user comment that came to the top on this title on the IMDb is headed, “Horrible!”) I will not attempt to make a case for this movie, though I’ll freely admit to liking its absolute insanity. Actually, Cook isn’t a bad model—physically—for Holmes, but it rather ends there. Mostly, the film is a collection of odd spoofs and at least one Cook and Moore routine (a variation on their “One Leg Too Few” skit about a one-legged man auditioning for the role of Tarzan) more or less tied to the story. It’s a matter of taste—or lack thereof—as to how one responds to it. If you can resist a Cockney Jewish-accented Holmes visiting a brothel and opting for something that includes “a complimentary grape” (“What an odd way to spell ‘grape’—with an ‘o’”), then you can probably resist the movie. In any case, Conan Doyle, this ain’t.

So why the outrage over Ritchie’s film? Well, I suspect it partly stems from the idea that this is a big budget Christmas release that (theoretically) millions of people will see. After all, maybe a few hundred people went to the Morrissey Hound in its very limited theatrical life, so it hardly did any damage . The idea, presumably, is that Sherlock Holmes will afford a new generation a singularly warped view of the character. And it may do just that.

My argument would be that most of that generation probably neither knows, nor cares much about Holmes. The likely counter argument will be that a film such as this could prevent a “real” Sherlock Holmes picture from being made. Now, really, isn’t this wishful thinking? Does any but the most profoundly insular Sherlockian entertain the notion that a straight and faithful (whatever that means at this point) Holmes movie is going to be made at this point in history? With that in mind, isn’t it just possible that the Ritchie rethinking could conceivably draw a few curious viewers to actually read the stories?

Now, I like Sherlock Holmes just fine, but I’m not morbid about it. I haven’t read the stories in 20 years and I rarely watch any of the film versions these days, but I have mostly pleasant feelings about both. If I bump into one of the Rathbone-Bruce movies on TCM, I’ll probably leave it on, but that’s about as far as it goes. They simply aren’t personal hobby horses of mine. As a result, I’m looking at this fairly dispassionately—and possibly more at this point in time as someone who’s interested in Guy Ritchie as a filmmaker more than I’m interested in Sherlock Holmes as such. My view is already a little skewed, but I still find it amusing to watch persons of a literary bent engaged in the sort of railing I usually associate with the folks who get worked up over some departure—or even possible departure—from a superhero comic book, especially since so mant of the literati I know find such outcries rather silly.

I suspect this all has to do with our individual perceptions of what is or isn’t definitive in any given realm. Way back when I was researching the genesis of Tim Burton’s Batman (1989) for a book on Burton, I was struck by his realization that ultimately there is no version of anything that isn’t going to result in pissing off somebody. He was certainly right. There are still people who decry his Batman because of its somber tone, which is perceived as being out of keeping with the Batman of the 1960s comics and the Adam West TV show.

A greater furor erupted in 1992 over his Batman Returns for much the same reason—only the perception was that it added a new level of nastiness to the proceedings. The thing was that, yes, these films did subvert the cheerfully kiddie-centric Batman image. But the image they reflected not only was not only more in keeping with the more adult-themed comics of the films’ era, but they harkened back to the dark tone of the very first Batman comics.

At the same time, we now find the Burton films being denigrated by harder core comic fans for not being dark enough—especially in light of the very gloomy Christopher Nolan Batman pictures, Batman Begins (2005) and The Dark Knight (2008). All of this, to me, merely serves to illustrate that there’s often no such thing as a universally accepted definitive anything.

This past year Frank Miller gave us his filmic take on Will Eisner’s comic The Spirit. A whole lot of people were far from amused by what he did with (as opposed to what he did to) the material. Yet, as I understand it, Miller was a friend of Eisner’s and one wonders whether Eisner himself would have disaproved of the liberties Miller took with the material. Miller’s own statement that he planned on being faithful to the “heart and soul” of the material suggests that he both thought he was doing that, but indicates similarly that he had little interest in simply adhering to the comics.

Now, I’ve never read The Spirit in my life, but I know enough about the comic to realize that in oh so many ways Miller has kept to the—uh—spirit of the thing, if not the letter. It’s a nice touch, for example, that Miller kept the basic outfit for The Spirit—even to sticking with that slightly preposterous mask that Eisner added at the last minute so he could satisfy the demands of a publisher that the character had a costume. He’s also retained the often bizarre character names and the general loopiness of the plots. I am, however, fully aware that Miller has made it his own in other ways. Still, the very existence of this screwy film is perhaps the one thing that might one day lead me to read Eisner’s comic books.

As one of the handful of defenders of Miller’s film (I even made the Wikipedia page on it for being in the plus column), I think of the film as being not wholly dissimilar to radical Shakespeare. If a less highfalutin comparison would be more comfortable, I’ll put it on the basis of Tony Richardson’s 1965 film of Evelyn Waugh’s 1948 novel The Loved One. The essence is the same in Richardson’s film and Waugh’s novel, but Richardson’s film expands on the book to address issues that did not exist in 1948, adding to the things Waugh was appalled by. It seems a natural approach to me. It’s Richardson’s film of the book and it should reflect his view. If I want just the novel, it’s on my shelf with the rest of Waugh’s books. I find the film more interesting because of what it does with the material, not less interesting.

Miller’s The Spirit is in the same ballpark. Where Eisner found the world of comics wanting when he created The Spirit, so Miller appears to find the world of the comic book film wanting today. The seriousness of the modern comic book movie in particular seems to be motivating factor in the tone of his film, which is nothing if not playful. Miller’s approach is fanciful, but not in the camp silliness of the Adam West Batman TV series. This is a more rarefied world where the production design is part of the joke, where the faux Raymond Chandler noir narration is clearly a put-on, where the sheer preposterous nature of the story is constantly expanded. Yet, there’s a stunning level of coherence to the narrative and a visual elegance that actually honors Eisner’s description of his work as “sequential art” in a way that perhaps no other comic book film has—and this has yet to be recognized.

What this resulted in was—and is—a film that deliberately set the comic book movie back 20 years. Miller’s Tex Avery-ish approach to the material was a slap in the face of the increasingly serious tone of comic book movies. Frankly, I suspect this is what angered fans more than questions of fealty to Eisner. Comic fans had fought long and hard to gain some degree of literary respect—and in turn cinematic respect—and here comes this movie thumbing its nose at all that. One wonders how time will treat Miller’s The Spirit in this regard. After the far from overwhelming response to Zack Snyder’s Watchmen, it’s just possible that Miller was onto something. What Miller did—like it or not—was to make the definitive Frank Miller movie of The Spirit. What Snyder did was to try to duplicate the comic book itself. The results were essentially inert.

That’s really my point with any of this line of thought. There simply is no such thing as definitive except in the most completely subjective manner. Your definitive Dracula may be Christopher Lee. Mine is Bela Lugosi. Your definitive Sherlock Holmes may be Arthur Wontner or Jeremy Brett. Mine is Basil Rathbone with Peter Cushing a close second. And so on.

It hardly starts and stops with movies as such. I came home tonight to an e-mail from an old friend, who said she needed to revisit Ken Russell’s film of Tommy (1975), which she had only watched because she’d seen the stage version and enjoyed it. She didn’t much care for the film, because it was so different from the play, especially the approach to the music. (Yes, she and I will be having a long talk about this, I assure you.) The play has become her benchmark for the material. The film is mine, though I can enjoy the play to a degree.

When the film came out, many fans of the original 1969 album thought it subverted the original and didn’t care for the sound of the film. In some ways, this referred to the vocals, but in others the objection to the overall sound really meant that they didn’t like where composer Pete Townshend was musically at the time. If you compare the film’s soundtrack to Townshend’s Who album Quadrophenia from the same period, they are startlingly similar in sound and orchestration. But that didn’t alter the fact that the film was not their definitive Tommy. Yet, the film is definitive as Russell’s Tommy. That’s as it should be.

In the end, that’s what I’m hoping for from Guy Ritchie’s Sherlock Holmes—that it will be the best damned Guy Ritchie version of the material possible. I’d like to hope that my Sherlockian friends who are appalled by that prospect may decide to look at in that light. If not—hey, guys, you’ve still got the Conan Doyle stories to fall back on. That’s not going to be taken away from you.

I agree with you, Ken. I’m really looking forward to see what both Downey and Ritchie do with this. There have been so many interpretations over the years, and to be honest, I’ve enjoyed most of them, so one more certainly isn’t going to be earth-shattering.

And let’s be honest, Doyle wanted to end the whole thing at Reichenbach Falls, but the public wouldn’t let him, so you might say even Doyle was coming up with new interpretations of Holmes.

“Your definitive Sherlock Holmes may be Arthur Wontner or Jeremy Brett. Mine is Basil Rathbone with Peter Cushing a close second.”

I’m glad you mentioned Peter Cushing’s take on Holmes; while I like Jeremy Brett the best, Cushing was a darned close second. I’m not sure that too many people are aware of him playing the part.

The idea, presumably, is that Sherlock Holmes will afford a new generation a singularly warped view of the character.

I think it a moot point; the new generation probably already has a warped view of Sherlock Holmes despite (or perhaps because of) his prominence in popular culture.

Miller’s Tex Avery-ish approach to the material was a slap in the face of the increasingly serious tone of comic book movies.

Which is ironic, considering Miller’s Batman work is widely credited with ushering in a new, darker age of comics.

I really do find it shocking that so few people — even critics of otherwise impeccable perspicacity — realized that The Spirit was supposed to be silly.

She didn’t much care for the film, because it was so different from the play, especially the approach to the music.

I once knew a man who complained that a movie deviated from its novelization — not its source material, mind you, but its novelization, which was supposed to be an adaptation of the movie!

I agree with you, Ken. I’m really looking forward to see what both Downey and Ritchie do with this.

Now, if I could only get you to bend on the question of Miller’s The Spirit. I know that the argument is likely to be that there are scads of Holmes movies, but only this one chance to make a Spirit movie. That I will concede, but the question arises as to who was likely to make it?

I’m glad you mentioned Peter Cushing’s take on Holmes; while I like Jeremy Brett the best, Cushing was a darned close second. I’m not sure that too many people are aware of him playing the part.

Well, apart from that short-lived Brit TV series was he ever Holmes other than in the Hammer Hound of the Baskervilles (“It’s the pictue with that bone-chilling howl!”)? That’s the performance I’m basing my statement on. Cushing was the first Holmes I saw who really seemed to capture the drug addict quality.

I’ve never warmed to Brett, though that may have more to do with just not liking the style of the admittedly few episodes of the Granada TV series.

the admittedly few episodes of the Granada TV series.

That should have read “few episodes of the Granada TV series I’ve seen.”

I think it a moot point; the new generation probably already has a warped view of Sherlock Holmes despite (or perhaps because of) his prominence in popular culture.

Very likely — and that ain’t new. Ever hear the Firesign Theater’s Giant Rat of Sumatra? I was either still in, or just out of high school when that came around.

I really do find it shocking that so few people—even critics of otherwise impeccable perspicacity—realized that The Spirit was supposed to be silly.

How can you not realize that? That just baffles me. Almost as baffling is the claim that the story is impossible to follow. There may have been a few touches I missed the first time, but the narrative was pretty darn easy to follow.

I once knew a man who complained that a movie deviated from its novelization—not its source material, mind you, but its novelization, which was supposed to be an adaptation of the movie!

That’s just damn weird.

“the Hammer Hound of the Baskervilles…That’s the performance I’m basing my statement on.”

I’m not aware of any others, either, and I also base my view on the Hammer film. Interestingly, his Hammer cohort Christopher Lee played the part of Holmes as well in (I think) two films of the sleuth, but he still didn’t match Cushing.

A lot depends on your first exposure to the material being depicted. Being a big fan of Stephen Sondheim’s SWEENEY TODD, I was disappointed in Tim Burton’s film version (and I’m a fan of Burton) because he altered the musical score which is a personal favorite of mine. Now that the initial shock has worn off, I like SWEENEY more than I did at first but I still have issues with it because of what I bring to the table.

I was not a fan of the earlier Frank Miller adaptations SIN CITY and 300 but I really liked THE SPIRIT for precisely the reasons that you gave. After the passage of a few years, I’d be willing to bet that it will be more highly regarded than it is today. A few people actually walked out of the screening I attended.

Regarding Sherlock Holmes, I grew up with the Rathbone-Bruce films but I enjoy the characters so much that I’m interested in almost any interpretation. I will be very curious to see what Guy Ritchie will do. My personal favorites are Christopher Plummer and James Mason in Bob Clark’s MURDER BY DECREE and Robert Stephens and Colin Blakely in Billy Wilder’s THE PRIVATE LIFE OF SHERLOCK HOLMES. By the way on July 7th Kino plans to issue the restored version of the 1922 film starring John Barrymore with Gustav von Seyffertitz as Moriarty.

Interestingly, his Hammer cohort Christopher Lee played the part of Holmes as well in (I think) two films of the sleuth, but he still didn’t match Cushing.

In all honesty, Lee — at least till his old age — always struck me as more of a presence than an actor. (The Gorgon is a notable exception.) But I’ve never seen Lee’s Holmes, which I think was also limited to one big screen (and a couple TV films) appearance in the German Sherlock Holmes and the Deadly Necklace.

“Now, if I could only get you to bend on the question of Miller’s The Spirit.”

I suppose I’ve softened my views on it a bit in my old age, but I still don’t think Gabriel Macht was the best choice for the part, even though he is a fine actor and did some good things with the role, I just spent too much time with the comic and have this vision of a larger, more muscular and comically goofy Spirit. And I’ll probably watch it again. How’s that for a start?

“I’ve never seen Lee’s Holmes, which I think was also limited to one big screen (and a couple TV films) appearance in the German Sherlock Holmes and the Deadly Necklace.”

You’re correct. According to IMDB, he played Holmes in that one film, but also played Mycroft Holmes in ‘The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes’. While I never saw that film, I did see ‘Deadly Necklace’ many years ago.

Wonderful essay and much food for thought, with great examples which I’d like to touch on later. A few things just this moment, though. First, on the general notion of popular images versus what’s actually there in the source text, a little while back I had someone question the claim that Sesame Street’s Muppet Count was in any way influenced by Bela Lugosi: “Isn’t the hair, the voice, the evening dress all in the Bram Stoker book?” And of course none of it is (indeed, the main visual I’ll always retain of the Stoker vampire is the hairy palms and I have a vague recollection of bad breath too.) The same goes of course for Holmes and the Frankenstein monster, to say nothing of Robin Hood as a being in Peter Pan green tights (though of course fairytale and folklore are even more fluid, yet that really is the image that has persisted despite having next to no actual basis in any source text).

I also missed my window to comment on The Spirit, being unable to see it until it made the second run circuit. I’m definitely glad I saw it in a theater and I think I enjoyed it more as a result. You’re spot on in calling it “the definitive Frank Miller movie of The Spirit.” However, it’s definitely not really in the same spirit as Eisner, though I agree that as a friend of Eisner, Miller seems to have respected the source material as comic works without it really showing in the movie. So it was less the jokiness and Samuel L. Jackson as a Nazi that was off to me. In fact, Jackson’s Octopus is an enormous improvement to me over Eisner’s more sporadically used evil genius “whose true face is never revealed, a master of disguise.” But many of the changes seemed less a spoof of grim comic book movies and grim comic books (and of course Miller himself gave the world both grim Batman *and* the graphic novel “300”) than actual examples of it, perhaps less grim than angsty: the Spirit’s tetchy relationship with Commissioner Nolan and keeping his identity a secret from Ellen, the Spirit no longer being a generally pleasant, wholesome crimefighter with a sense of humor (though the last was not utterly lost) so much as a shellshocked person struggling to come to grips with his “death” and with this strange nymphomaniac attitude towards woman (all woman, plain or babes). Oh, and Lorelei Rox (a one-shot character in the comics) as this weird watery symbol of death. But in small touches (especially the use of semi-black and white or sepia tones for flashbacks or other scenes) and some specific scenes or quotes (Dolan’s line about how much can happen to a man in 10 minutes referring to a specific story which like many was basically a character study with the Spirit barely making a cameo to justify it being there in the papers; the scene where he first comes to Dolan after reviving) are spot on and especially the overall *style*. Discount the gore (which was actually so cartoonish as to float by even one as squeamish as me, though the fate of “Muffin” did gross me out in a visceral way) but the angles and even the mixture of 30s/40s sets, costumes, and cars with things like fax machines and modern computers and so on is very like Eisner. The Chandler-style “My city needs me” stuff felt too earnest and overdone to actually be parody and utterly out of character (the Spirit wasn’t one to brood nor especially introspective on the whole), but undercutting this with the Spirit being associated not with bats and rats but fluffy meowing pussycats was a huge plus.

I’ve told friends that while I think Miller could easily have avoided needless things like making the Denny/Dolan relationship more cliched and combative and little bits, I think a faithful version by Miller would have been worse and less fun, and given the nature of the source (never actually comic books, with some exceptions later, so much as longer “Sunday comic supplement” stories in one piece as opposed to the endless serialization of Flash Gordon) I’m not sure a truly faithful adaptation is either possible or preferable. So with the Octopus, Gabriel Macht’s The Spirit (his performance more than the material he’s given at times, as well as his look, really capture the character, the type who would say “By golly” and really mean it) and Miller’s visuals and just plain insanity, it beats out both “300” and revisions like “The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen” (taking liberties with a comic book which itself is founded on the premise of taking Victorian-era fictional characters and making a kind of “Literary Superfriends” out of them with some liberties and a lot of dark or bawdy humor, thus further undermining the whole notion of faithfulness and “definitive” images.)

Finally, and I may have mentioned this elsewhere in these comments, I love film adaptations of literature (though in my childhood I’d keep my impatient sister waiting to see a movie until I had a chance to finish the book, if we had it.) But there are films that are faithful (or “good”) adaptations, or good movies, and the very few that are both. And something like Miller’s “Spirit” which objectively speaking may in fact be neither but is a whole lot of fun to watch. This applies equally or even moreso to Dickens; outside of weird “chung chung” metallic soundtrack for transitions and MTV style fade-in transitions, I loved the BBC “Bleak House” from a few years ago which did not take the usual Masterpiece Theater road but treated it as a serial, a soap opera, which in many ways it was, but it was faithful in spirit and often in letter, but the variations in some cases were actually improvements as far as streamlining those enormous Dickensian casts or making the material coherent and filmable (adding a clerk who wasn’t in the book but who the lawyer would certainly have had, acting as bystander, giving the character a confidante and the actor someone to play off in scenes that couldn’t be dropped but would otherwise just be someone sitting over papers for four minutes, and filling expository gaps handled in narration) and so on. And “The Loved One,” though I felt Robert Morse’s playing sometimes made the character less devious and more naively astonished, was faithful to the spirit and often even the letter in the first half before going into Richardson and Terry Southern’s own bugbears (i.e. the space and arms race and military complex and so on) but which fit so well with Waugh; Mrs. Joyboy goes from merely unpleasant to a monstrous cinematic image, and yet the weaker elements of the novel are sometimes boosted (as with the best such) just through direction, playing, and apt casting, so John Gielgud’s character and his death take on a poignance not in the novel, while as a kind of equivalent to the Waugh narrative sarcasm you get background visuals like the British club in Hollywood inexplicably being shaped like a cartoon whale.

In general, neither radical revisionism nor slavishly clinging to every paragraph and minor character ultimately produce a work that will actually stand as a film (for all the liberties James Whale took with Mary Shelley, his version of Frankenstein still trumps any of the attempts by the likes of Branagh or others to be more faithful but instead gave us FrankenBonham Carter over a hunchbacked Dwight Frye.) Anyway, enough on this from me for now, mayhaps more later when I’ve had more time to muse and to take in all of your points and examples.

You’re correct. According to IMDB, he played Holmes in that one film, but also played Mycroft Holmes in ‘The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes’. While I never saw that film, I did see ‘Deadly Necklace’ many years ago.

Private Life is an oddity. It’s a movie I like pretty well while it’s establishing itself in vignettes, but I find it a lot less interesting once it settles into its Loch Ness Monster scenario. Unfortunately, that’s the largest single portion of the film — a definite drawback for me. I’ve never seen Deadly Necklace, but, if memory serves, Lee’s voice is dubbed by someone else, which would make his performance a little hard to judge.

Reimagining is not only an attractive concept, I feel like it’s a necessary one. As someone who self-identifies as a “fan” of many of the bits of popular culture that are now being adapted into films, I’ve been finding myself alone among peers in calling for more deviation from the source material.

I think a good example is the Harry Potter film series. The early entries were tedious, verbatim productions of the novels. It wasn’t until Alfonso Cuaron arrived midway through the series that filmmakers began to shake up the mythology that was rapidly becoming second nature to half the country.

As a moviegoer, I’m just interested in seeing word-for-word adaptations. Lots of people decried the recent Wolverine picture for being too far removed from established stories. Well, that sounds like a good thing to me. We comic book perusers have already read all these “big” Wolverine stories; do we really need to see them again? Though I do find quite a bit of merit in Snyder’s Watchmen, it does in fact suffer from being far too attached to the source material.

The recent Star Trek seems a good example of playing fast and loose with established canon and already-known stories while, in its theme, mood and execution, embodying the frenetic Star Trek that has always existed in the minds of those who enjoy it, rather than necessarily being exactly like the show/movie series itself.

I grew up with the Rathbone/Bruce Holmes movies but I enjoy the characters so much that I’ll sit through anything even the Stewart Granger version with William Shatner as Stapleton! My personal favorites are Christopher Plummer and James Mason in “Murder By Decree”.

I’m also a Guy Ritchie fan excluding “Swept Away” so the results of the new movie should be interesting if nothing else. Not your father’s Sherlock Holmes to say the least. I just hope they don’t push it back because preview audiences don’t like it.

As for your grandfather’s Sherlock Holmes, I saw on Amazon where Kino is planning to release a restored version of the 1922 John Barrymore version which features Gustav von Seyffertitz as Professor Moriarty. The release date is July 7th.

>Kino is planning to release a restored version of the 1922 John Barrymore version which features Gustav von Seyffertitz as Professor Moriarty. The release date is July 7th.

Gustav von Seyffertitz! The name itself is music! Too beautiful, too beautiful, too beautiful.

Seriously, I’ve read M. Hanke and others remark on the great Gustav’s Moriarty and I’d love to see it in comparison to the likes of Zucco (my own personal favorite, well apart from Leo McKern in “Sherlock Holmes’ Smarter Brother”) and Atwill.

Whenever I hear people complain about remakes or revisions of adaptations not holding up to the originals they love so dearly, I remember a story I once heard, where Raymond Chandler was being interviewed and the interviewer asked, “What do you think of Hollywood butchering your books the way they do?”

Chandler replied by taking them to his study, pointing to his bookshelf and saying, “They haven’t done anything to my books, they’re all still sitting there.”

A lot depends on your first exposure to the material being depicted.

And your reaction to it. That can also be a very large factor. I think I first heard the entire album of Tommy in 1970. I didn’t like it much. I know I heard it again in 1972 (the circumstances, which I’ll omit for the sake of decorum, are too memorable to forget) and still didn’t like it. I went to see the film because I was an Elton John fan at that time — no other reason. The changes in the music took care of my objections and I bought the soundtrack the next day. I’ve gotten to a point where I like the original album, but I prefer the film track (and the Isle of Wight Concert recording, come to that). Then too, the film is more dramatically coherent. It may have been that I was too young to “get” the album when I heard it, but there’s little doubt that it was Russell who made the work relevant in terms of western religion, which is more comprehensible to my worldview than Meher Baba.

Being a big fan of Stephen Sondheim’s SWEENEY TODD, I was disappointed in Tim Burton’s film version (and I’m a fan of Burton) because he altered the musical score which is a personal favorite of mine. Now that the initial shock has worn off, I like SWEENEY more than I did at first but I still have issues with it because of what I bring to the table.

This kind of continues the same pattern as Tommy for me, because I didn’t care for stage show recording. I didn’t like the chorus thing in the least and it never made the film. Similarly, I absolutely cannot abide that playing to the last row of the balcony style of singing that’s in the show and which is much toned down in the film. As a result, the film made the score much more to my liking.

I was not a fan of the earlier Frank Miller adaptations SIN CITY and 300 but I really liked THE SPIRIT for precisely the reasons that you gave. After the passage of a few years, I’d be willing to bet that it will be more highly regarded than it is today. A few people actually walked out of the screening I attended.

I loathed 300 (apparently, Miller was none to fond of it either), but I did like Sin City — not, however, to the point of feeling like defending it just now without seeing it again. I think I noted in the review of The Spirit that is to comic book movies what the 1967 Casino Royale was to spy movies. While the original Casino Royale was one of the most financially successful film of its year, it was critically savaged. Its reputation has improved with every passing year.

By the way on July 7th Kino plans to issue the restored version of the 1922 film starring John Barrymore with Gustav von Seyffertitz as Moriarty

What a way to celebrate Gustav Mahler’s birthday! Now, John Barrymore may be my favorite actor of all time, and putting Gustav von Seyffertitz in anything is always a plus, but the 1922 Sherlock Holmes…I’m reminded of William K. Everson’s conversation with Holmesian scholar Bobby Pohle after the first restoration of the film was shown. Afterwards, Bobby said, “Well, it looks like it has everything now,” to which Everson replied, “Except style.” Oh, I’ll buy it and I’ll watch it — hopefully on a big screen, which will likely help — but I’m not expecting much from a second look at it. A nicer print may help, of course.

I just spent too much time with the comic and have this vision of a larger, more muscular and comically goofy Spirit.

So ideally, whom would you have cast?

And I’ll probably watch it again. How’s that for a start?

Well, it’s certainly a start — especially compared to your initital reaction to the film!

First, on the general notion of popular images versus what’s actually there in the source text, a little while back I had someone question the claim that Sesame Street’s Muppet Count was in any way influenced by Bela Lugosi: “Isn’t the hair, the voice, the evening dress all in the Bram Stoker book?” And of course none of it is

I guess it’s not unusual for a later image to overwhelm the original. Read Earl Derr Biggers’ description of Charle Chan in The House Without a Key. He looks nothing Warner Oland or Sidney Toler or even Roland Winters. At the same time, I suppose it’s better than people who think “They’re all going to laugh at you!” is from some Saturday Night Live schtick and are completely unaware that it comes from Piper Laurie in Carrie. Someone once upbraided me for using the line, “Everytime that man opens his mouth, he subtracts from the sum total of human knowledge,” claiming I had stolen it from Billy Madison. I assume the line or something like it is in Billy Madison, but I don’t know and it’s not a piece of research I’m planning on on undertaking. However, if it is in there, then the writers of Billy Madison stole it from the same place I did, The Dark Horse (1932). I don’t mind being accused of lifting the line, since I did and wasn’t trying to hide the fact, but at least get the source right!

But many of the changes seemed less a spoof of grim comic book movies and grim comic books (and of course Miller himself gave the world both grim Batman *and* the graphic novel “300″) than actual examples of it, perhaps less grim than angsty

I can’t refute the comparisons with the comics, but I don’t really see the things in The Spirit as truly grim or particularly angsty. Perhaps it’s just tone that makes me feel that way. While, yes, Miller did give us the grim Batman, it appears that he now feels that it’s all been taken to an even greater — and humorless — extreme. That’s what I’m getting out of the tone of The Spirit — that it’s kind of the anti-Dark Knight. There are angsty things in The Spirit, but they’re not really played for heavy grimness. I get no sense of nihilism or true mean-spiritedness.

In general, neither radical revisionism nor slavishly clinging to every paragraph and minor character ultimately produce a work that will actually stand as a film

No, that takes something altogether different that can’t be so easily pinned down to a simple set of rules.

I’ve been finding myself alone among peers in calling for more deviation from the source material.

A friend of mine actually catalogued the departures between the Watchmen book and the movie. In quite a few cases, this was interesting — sometimes because things were included and then just dropped to a point that the cut should have been more severe — but in others, it seemed kind of beside the point.

I think a good example is the Harry Potter film series. The early entries were tedious, verbatim productions of the novels. It wasn’t until Alfonso Cuaron arrived midway through the series that filmmakers began to shake up the mythology that was rapidly becoming second nature to half the country.

A most excellent example. I found the first two films okay. Certainly watchable enough, but they were almost superfluous to me — like novels for the illiterate. I’d far rather have the filmmaker’s take on the material than to see the material simply reproduced.

“So ideally, whom would you have cast?”

Bill Irwin in a muscle suit. I think he’s one of the few actors that has the physical abilities and training to match what the Spirit went through in the comics. He is a little small, though.

Seriously, I’ve read M. Hanke and others remark on the great Gustav’s Moriarty and I’d love to see it in comparison to the likes of Zucco

Kinda hard to top Zucco.

Bill Irwin in a muscle suit. I think he’s one of the few actors that has the physical abilities and training to match what the Spirit went through in the comics. He is a little small, though.

Don’t you think he’s just a little old?

Probably, I just haven’t seen other actors have the talent to do some of the physical shtick i’ve seen him do.

After just seeing the trailer,and finally taking a peek at the Holmes thread, I can see what you mean “this has caused much consternation among the Sherlockian set.” Was I this bad about THE SPIRIT?

I think they movie looks like it’s going to be quite enjoyable!

of course Miller himself gave the world both grim Batman *and* the graphic novel “300″

True, but even Miller’s darkest work flirts with self-parody. (The Dark Knight Returns, for instance, features a cameo by Ronald Reagan and several homages to Max Allen Collin’s work on Dick Tracy.) His more recent comics don’t flirt with self-parody so much as wed self-parody with a high mass.

I won’t defend 300, because it’s Miller’s poorest work. But again, the whole remake aesthetic is important to understanding its intent. Miller saw Maté’s 300 Spartans when he was a boy and was struck by the idea that true heroes die without any reward. That idea became central to his ethical system and inextricable from his ideas about democracy and civic virtue. Of course his rewrite of the Battle of Thermopylae would be somewhat self-important.

While, yes, Miller did give us the grim Batman, it appears that he now feels that it’s all been taken to an even greater — and humorless — extreme.

Indeed, Miller’s recent work on The Dark Knight Strikes Again and All-Star Batman and Robin almost feels like an apology for The Dark Knight Returns.

And in any case, Miller’s Batman wasn’t angsty for angst’s sake. Batman’s obvious mental instability forced the readers to question the extent to which they were willing to identify with a superhero who never attempted to justify his own behavior and even admitted he was a criminal.

How can you not realize that? That just baffles me.

It baffles you, it baffles me — but plenty of people more astute than I miss the point. Go figure.

Sometimes, I feel that Miller has no desire to explain the point to people who aren’t willing to immerse themselves totally in his explorations of base emotions and two-dimensional character types. It’s an expression in metatextual form of the stories’ driving themes: Miller’s stories are all about projection and simulation, and to realize that deeper aspect, you have to project onto them and buy into their simulations of superheroism, noir, etc.

I’d far rather have the filmmaker’s take on the material than to see the material simply reproduced.

So would I. The qualities that make a story so wonderful in one medium don’t always translate to another. I mean, even if it were possible to film every page of a Harry Potter novel, the viewers wouldn’t get the same insight into Harry’s internal landscape, so the director needs to find an alternative means of representing the character.

I’ve often tried to defend Baz Luhrmann’s Romeo + Juliet (1996) against those who would dismiss it as offensive trash trying to be hip. Luhrmann was once quoted as saying “Shakespeare was a rambunctious, sexy, violent, entertaining storyteller. We’re trying to make this movie rambunctious, sexy, violent and entertaining the way Shakespeare might have if he had been a filmmaker”. Although I do think a modern Shakespeare would probably make a slightly different movie, I also think that Shakespeare would appreciate and respect Luhrman, and his own unique stylization. I love when a filmmaker is unique enough in their style that you can recognize their work without originally knowing that they were the creator. Rethinkings and/or reworkings is just another way of saying that the director has taken his own artistic license with the proceedings. If one looks at film as an art form, then even if you don’t personally like the end result, how can this be a bad thing. Guy Ritchie’s Sherlock Holmes is just another example of a stylized director breaking into a more pop-culture realm (much like Tim Burton’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory) where the conservative masses don’t want their idealistic comfort zones threatened by ‘art’. I will never understand why anyone would fight originality, but now I’m getting off of the point, and starting to go on a tangent.

After just seeing the trailer,and finally taking a peek at the Holmes thread, I can see what you mean “this has caused much consternation among the Sherlockian set.” Was I this bad about THE SPIRIT?

Uh, let me look…You were, let us say, more succinct — and you’d actually seen the film. Your post — till I started poking at you — consisted of “The Spirit. What a waste of time!”

It baffles you, it baffles me—but plenty of people more astute than I miss the point. Go figure.

In the immortal words of Larson E. Whipsnade, “It baffles science!”

Sometimes, I feel that Miller has no desire to explain the point to people who aren’t willing to immerse themselves totally in his explorations of base emotions and two-dimensional character types.

Great. So in the case of the film of The Spirit he leaves it to boobs like me who don’t even really like comics! What a mensch!

I’ve often tried to defend Baz Luhrmann’s Romeo + Juliet (1996) against those who would dismiss it as offensive trash trying to be hip. Luhrmann was once quoted as saying “Shakespeare was a rambunctious, sexy, violent, entertaining storyteller. We’re trying to make this movie rambunctious, sexy, violent and entertaining the way Shakespeare might have if he had been a filmmaker”.

I didn’t like it when I saw it, but I would never have argued against on those grounds, because Luhrmann is, of course, right. In the meantime, having seen Luhrmann’s three other movies, I’m inclined to want to try Romeo + Juliet again. It is, in fact, on my shelves. I have yet to get around to it.

the conservative masses don’t want their idealistic comfort zones threatened by ‘art’.

The proper function of art is ought to be to threaten our comfort zones — at least on occasion!

I will never understand why anyone would fight originality, but now I’m getting off of the point, and starting to go on a tangent.

Go ahead, if you like.

“…the trailer suggests considerably more action than is generally associated with the detecting duo.”

Perhaps they’re are afraid of another “Van Helsing?”

This sounds like the same fooferaw (sp?) that arose at the time of “Young Sherlock Holmes” because “Holmes and Watson didn’t meet at university.” Didn’t spoil MY enjoyment of the film. (And while we’re talking comic hero movies, I thought Alec Baldwin’s “The Shadow” was very good, even though it bombed big time.)

Personally, I would have switched the actors in the lead roles, Law for Holmes an Downey for Watson. It seems a better fit to me.