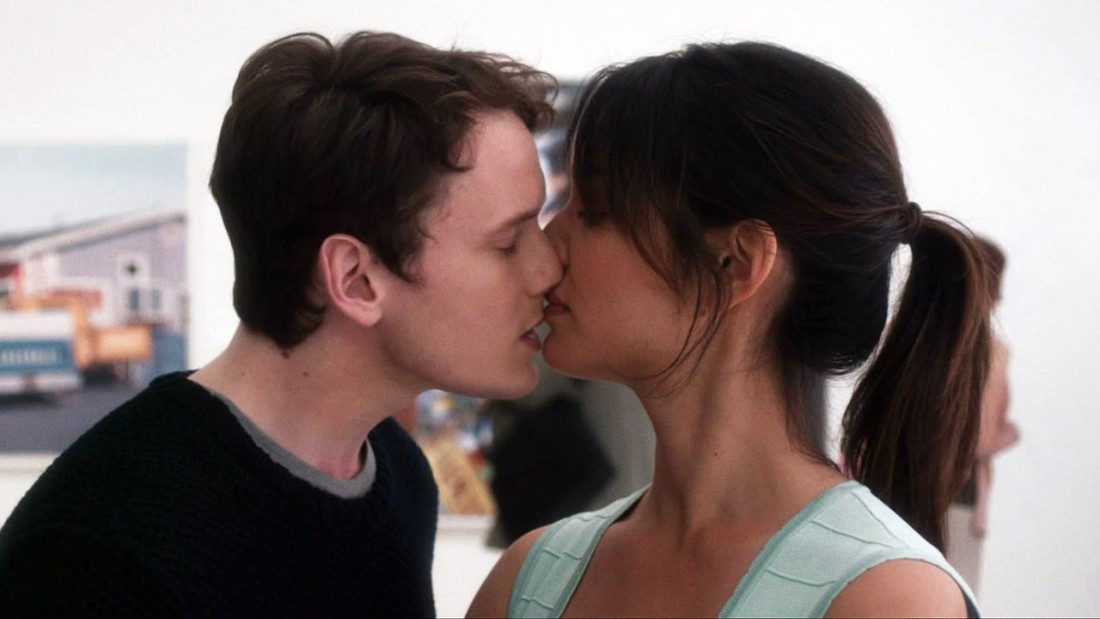

Victor Levin’s beguiling romantic comedy about struggling young Jewish writer Brian (Anton Yelchin) and older married French woman Arielle (Bérénice Marlohe, Skyfall) is a charmer from beginning to end. (It’s also the movie that in a fair world would make Yelchin a star.) It is a film in which boy and girl not only meet cute, they meet sophisticated cute. Brian isn’t just attracted to this beautiful woman, he’s intrigued by the foreign aroma of her cigarette — a smell he once encountered in a restaurant and that he thinks is either French or Spanish. Hoping for French (since he can’t speak Spanish), he starts chatting her up in what, yes, turns out to be her native tongue. After a few exchanges about distrusting non-smokers and a few awkward missteps by Brian (note: sophisticated older women don’t much like having their name equated with a Disney cartoon character), they make plans to meet again — between 5 p.m. and 7 p.m. This is every inch a movie — almost a fantasy set in a vague past (when was the last time you could smell a cigarette in a New York restaurant?) and a New York City that only ever existed in movies. And this is part of its charm — it’s less the world as it is than the world we might wish existed.

Brian, however, is an American innocent of the first water. He has no idea that the specific two-hour blocks of time Arielle is able to give him are part of French tradition of allowing married folks to act like they aren’t married for two hours a day — hence the title of the film. It takes a couple of dates for him to learn this, and he — not surprisingly — is shocked to his prudish roots. In fact, he tries to break off the relationship, but he’s already hooked. Soon he’s even been invited to dinner by Arielle’s husband, Valery (Lambert Wilson, Of Gods and Men), where he not only meets Valery’s mistress, Jane (Olivia Thirlby) — who just happens to be an editor at Farrar, Strauss and Giroux — but such heavy-hitters as philharmonic conductor Alan Gilbert, restaurateur Daniel Boulud and social activist Julian Bond (all played by themselves).

This is all like Wonderland to Brian, who refutes Arielle’s assurances that it’s all fine with a litany of clichés about no such thing as a free lunch, the other shoe will drop, the rent will come due, etc. The horrified Arielle wonders, “Who raised you?” He matter-of-factly answers, “Jews.” Soon he introduces his parents (Glenn Close and Frank Langella) to her. They’re delighted — until they find out she’s married and has two children. But soon mom is won over, while dad tries his damnedest not to be. Things develop — too quickly for believability, but this is hardly a film for that concern — and Brian gets his break as a writer, and Arielle does the one thing she had not planned on by actually falling in love with him.

There’s more, of course, and that’s actually more plot than I’d normally tell, but the plot is really the least appealing or impressive aspect of the film. The film’s timeless quality is so effortlessly conveyed that you barely notice that cellphones are rarely in evidence and not much used, that computers have the month and day on them without the year, that publishers are still sending out actual rejection or acceptance letters (you know, an envelope and all that). Levin makes all this easy to just accept. He’s a very shrewd director in other ways. There is a beautiful stillness to the film. The generally fixed camera (hand-held camera only appears if it’s a moving shot) gazes at the action without quite intruding. That may sound easy and even uncinematic, but it’s neither. The attention to detail is terrific — even in simple ways. When Brian meets Arielle for their first hotel-room tryst, her lavender dress matches the roses in the vase.

Owing to the film’s New York setting, the literary angle, Brian’s narration and the Jewish element, 5 to 7 inevitably calls the films of Woody Allen to mind, especially Manhattan (1979). That is also a very still film for the most part, with scenes often playing in long-shot. But it never really feels like an Allen knockoff. The tone of Levin’s film is more guileless than Allen — less knowing — and that’s as it should be with a character like Brian at the center. It’s also what makes the film its own animal, as does the final scene (which some have questioned), because it’s the scene that proves that Levin actually believes what he’s selling. Rated R for some sexual material.

I’ve only spent five hours in New York City, but this film has an insider’s feel for the place. Love Is Strange has this sense as well.

I’ve spent about three weeks there, but this was, I believe, before you were born. Still and all, yes, both films feel authentic to my experience.

Despite the split shows, this did remarkably well and is being held over for another week — but it’s down to two shows a day come Friday (1:55, 6:55).