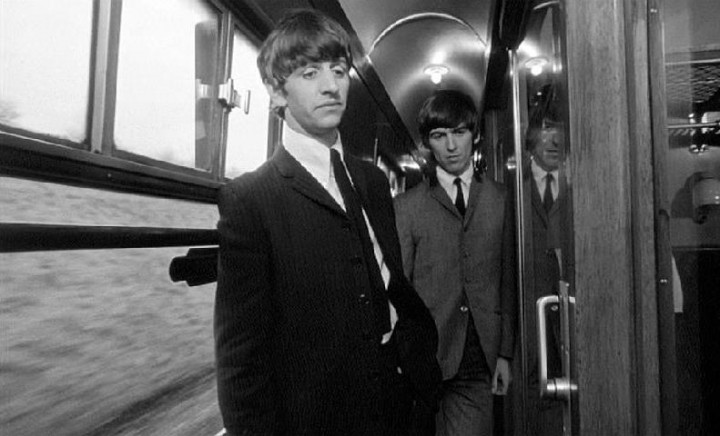

This year marks the 50th anniversary of Richard Lester’s A Hard Day’s Night (1964), the movie that both cemented Beatlemania and served — and still serves — as the most persuasive chronicle of that phenomenon. The first time I saw A Hard Day’s Night, I was 9 years old. It may be hard to believe now, but the kids in the theater screamed just as if they were at a concert every time the Beatles sang. The theater I saw it in — the State Theater in Lake Wales, Florida — has since been divided into a Jehovah’s Witness Kingdom Hall and the Young Republicans Club. Fortunately, time has been far kinder to the movie than to the more concrete pieces of my childhood. The film feels as fresh and inventive today as it did in 1964. It has become something more, as well: a document of an era.

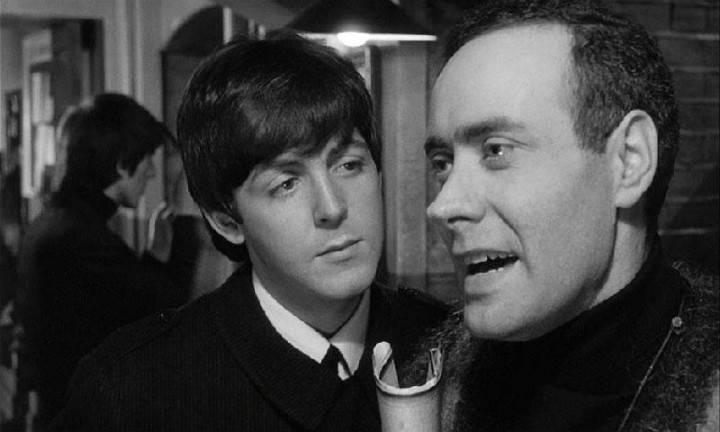

The irony here is that A Hard Day’s Night is often incorrectly described as a documentary, which is the one thing it never was and was never intended to be — considering its carefully crafted screenplay by the highly regarded Welsh writer, Alun Owen. Yet time has made the film the ultimate documentary on the myth that was the Beatles and the phenomenon that was Beatlemania (the film’s actual shooting title). A Hard Day’s Night’s plot can be summed up in one sentence: The Beatles go to the south of England to appear on a TV special. Within that deceptively simple plot, however, director Lester and those four lads from Liverpool created something unique. A Hard Day’s Night not only defined and refined the public image of the Beatles, it established the basic style of 1960s filmmaking (it can, in fact, be called the birth of modern film) and caused the movie-going world to completely rethink the term, “a British picture.”

With very few exceptions at the time, a British pedigree on a film was box-office poison. After A Hard Day’s Night, the moniker actually became desirable. The British Invasion in film — like the British Invasion in music that parallels it — succeeded in capturing the social and aesthetic imagination of a generation, not in the least because it was such a breath of cheeky fresh air. The slightly rude, yet playful, sense of freedom that marked A Hard Day’s Night was a magnificent antidote to the well-crafted dullness of the 1950s and early-1960s films that had preceded it. As conceived, the film was nothing more than a vehicle to exploit the popularity of the Beatles as quickly and as cheaply as possible. After all, no one — not even the Beatles (Ringo wanted to make enough money to open a beauty parlor) — had any idea that they were anything but a Nine Day Wonder perched on the edge of that ninth day. But as Philip Norman noted in his book on the Beatles (Shout!), their popularity “fed on its own freakishness” — which isn’t hard to understand, because it offered a cheerfully mad sense of rebellion without the tiresome cynicism of the Angry Young Man school of thought.

In creating the picture of what it meant to be a Beatle — to feel trapped and moved about by forces over which one had no control and to want to break free of that feeling — A Hard Day’s Night hit a nerve with younger viewers. It offered an accessible identification in a way that earlier youth films never hit on — a sense of humor in the face of helplessness and the feeling that beliefs, personality and individuality could only be killed by authority if so allowed. In other words, authority reduced to absurdity is less threatening and more comprehensible. A few of the movie’s gags may not play today (not many modern viewers are apt to realize that the shirts George dismisses as “grotty” are Dave Clark Five apparel), but the film’s attitude, mood and depiction of the sheer joyfulness of youth are undiminished.

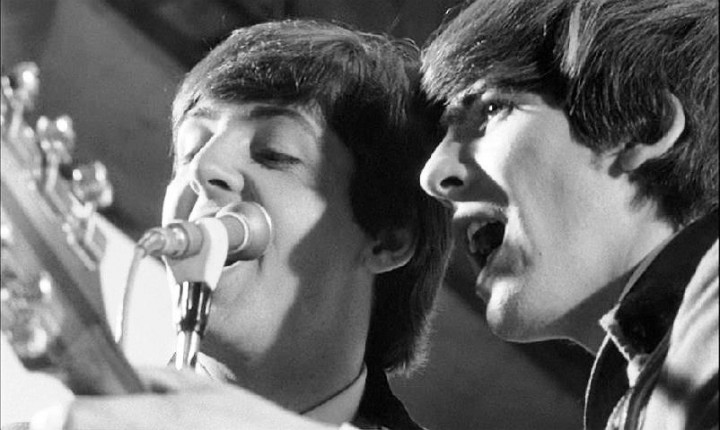

While it’s both reasonable and easy to lay all the claims to greatness at Richard Lester’s feet, it should be noted that much of what he did was inspired by French New Wave Cinema — but with his own comedic spin on it. For that matter, Lester had employed many of the same stylistic flourishes — jump cuts, stylized action, silent film comedy — with his 1962 film It’s Trad, Dad (US title: Ring-a-Ding Rhythm), but it failed to find much of a market, especially in the US where names like Helen Shapiro and John Leyton had little clout. What sets A Hard Day’s Night apart is, of course, the presence of The Beatles. With them, everything changed. And the mix of them with 32-year-old Lester gave the world something it had never seen — a film for the “youth market” that actually felt like it was made by young people rather than 50-year-old studio executives deciding what young people “should” like. (See any Beach Party, Elvis or 1950’s rock ‘n’ roll movie and you’ll know what I mean.)

It’s sobering to realize that the film is now 50 years old. If you saw the film when it was new, see it again and live it over. If you’ve never seen it, see it and perhaps come to understand what that heady era was like. Or see it for no other reason than the fact that it’s all too rare you can spend 87 minutes smiling and feeling positive about life.

The Asheville Film Society will screen A Hard Day’s Night Tuesday, April 29, at 8 p.m. in Theater Six at The Carolina Asheville and will be hosted by Xpress movie critics Ken Hanke and Justin Souther.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.