Roland West’s The Bat Whispers (1930) is unusual in that it’s the director’s talkie remake of his own silent film The Bat (1926). It’s also unusual in that this early sound film is actually far more fluid and cinematically adventurous than its silent counterpart. That’s not to say that the film doesn’t belie its stage-play origins, or that it doesn’t creak a little—but then, a little creakiness often adds to the atmosphere of an “old dark house” thriller, which this very much is. In fact, since the story—albeit without the character of an arch criminal called The Bat—dates back to Mary Roberts Rinehart’s 1908 novel The Circular Staircase, the 1920 play has a pretty good claim of being the very first such work. It’s certainly an essential, with every genre mainstay imaginable—a creepy old isolated mansion, a deranged killer on the loose, secret passages, thunder-and-lightning, an assortment of suspicious charactrers, a very peculiar detective etc. The premise finds elderly Cornelia van Gorder (Grayce Hampton), her niece Dale (Una Merkel) and her maid (Maude Eburne) being subjected to attempts to frighten them out of a house they’ve rented for the summer—until the arrival of the brusque (to say the least) Detective Anderson (Chester Morris), who is of the opinion that this is the work of The Bat, a seemingly unstoppable black-hooded, bat-caped criminal—and one who qualifies for a place in the pantheon of movie “monsters.” Perhaps even more interesting is the fact that—unlike most such films and plays—the story actually qualifies (probably because of Rinehart) as a bonafide work of “golden age” detective fiction in the bargain. As a result, you get both a horror film and a genuine mystery in one package.

Today The Bat Whispers is perhaps best known as Bob Kane’s inspiration for Batman, which is pretty obvious when you see the film. Oddly, Kane specifically cites this version and not the silent, yet the silent is just as clearly where the idea for the Bat Signal originated. (It’s more than likely that Kane has telescoped the two films in his mind.) Of course, The Bat is the villain and Batman is the hero, but the two do share similar dress-sense, a propensity for getting around on roofs with ropes that act in mysterious ways, and a degree of psychosis. The Bat is just more psychotic—and sociopathic in the bargain.

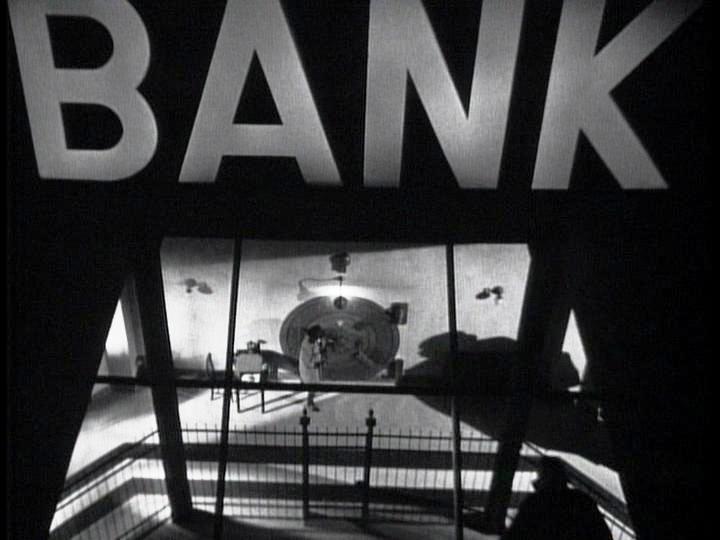

From a film standpoint—although one related to Batman—the most influential thing about The Bat Whispers is the impact it had on Tim Burton. It isn’t so much the Batman connection (apart from the idea of a psychotic Batman) as it is a stylistic influence that extends to non-Batman Burton films. The swooping camerawork and the heavy use of miniature sets that allowed for those shots are evidenced in Burton’s Batman (1989) and Batman Returns (1992), but they also show up in films as diverse as Edward Scissorhands (1990) and Ed Wood (1994). For that matter, the generic use of the gigantic word “BANK” and the set design in The Bat Whispers find themselves cropping up in Edward Scissorhands.

The film exists in two versions—the standard 35mm one and a 65mm “Magnifilm” widescreen version. This isn’t simply a case of the widescreen version being cropped and blown up, though that is the way the more elaborate effects involving moving camera were translated from 35mm to 65mm, because the bulky 65mm cameras were incapable of that kind of movement. The film was actually shot twice. Of the two versions, the 65mm has come to be considered the standard one in recent years, which is unfortunate, because it’s the lesser film in terms of cinematic style—and it reduces the impact of Chester Morris,’ shall we say, singular performance. Plus, some of Morris’ scenes with Dr. Vanrees (the always wonderful Gustav von Seyffertitz) have much less impact.

The problem is that West’s idea was that the widescreen format replicated the sense of seeing a live play, which it really doesn’t. It’s not hard to see how that is going to work out far too often, simply because it confuses the reality of two very different media. But the novelty of seeing a 1930 widescreen film seems to have won out for now. There were only a handful of such films made—mostly because the heat from the projector lamps caused the larger prints to buckle and warp, making them unusable after a few showings, which in turn made the process financially impractical. (The version of The Bat Whispers being screened for this week’s Thursday Horror Picture Show screening is the 35mm one.)

Strangely, The Bat Whispers proved to be Roland West’s penultimate film. The only thing he made after it was Corsair in 1931. The surprising thing about this is that West had been a fairly major—if not exactly prolific—silent director, and his first talkie Alibi (1929) snagged three Oscar nominations. So what happened? Well, it’s usually claimed that his career was ended because of his involvement in the mysterious death of his mistress, actress Thelma Todd, but that was four years after Corsair, so the story doesn’t hold up to scrutiny. The more likely explanation is that West either simply retired, or his much publicized penchant for working at night was finally just too much trouble. The funny thing is that The Bat, too, “only flies at night,” according to the film. Make of that what you will.

Wasn’t this remade again with Vincent Price, called ‘The Bat’, or was that a different story?

Yes, unfortunately, it was a remake.

And I should note that Mr. Shanafelt’s You Tube insertion is taken from the widescreen version.

Just from the clip alone, you really get a sense of the film’s astonishing visual sense, particularly in its use of moving camera with miniatures (and the murder/theft by window shade is quite ingenious!). Much of the camerawork and photography reminded me of Fritz Lang’s expressionistic films of the 1920s, such as DR MABUSE and METROPOLIS. Thanks for your post.

I’d never really thought of it in Lang terms, but, yes, some aspects of it are Langian.