Mike White is a smart guy. I’ve always enjoyed his work, specifically his early films created with director Miguel Arteta (Chuck & Buck, The Good Girl). But his ideas have always been more interesting than his finished projects, even those films that I’ve loved at different times of my life. This is true, again, of Brad’s Status, an OK but not great and, honestly, sort of a baffling film. Here we have the most blatant example of where White tends to get himself off track when not buoyed by strong collaborators. He’s kind of a downer, endlessly navel-gazing, looking within to divine whatever spiritual fruit he can, or whatever you call it when indie darlings grow up and make movies about their own half-remembered midlife crises. For a filmmaker as often high-minded as he’s shown himself to be, it’s disappointing to see him crafting a piece as unenlightened as this.

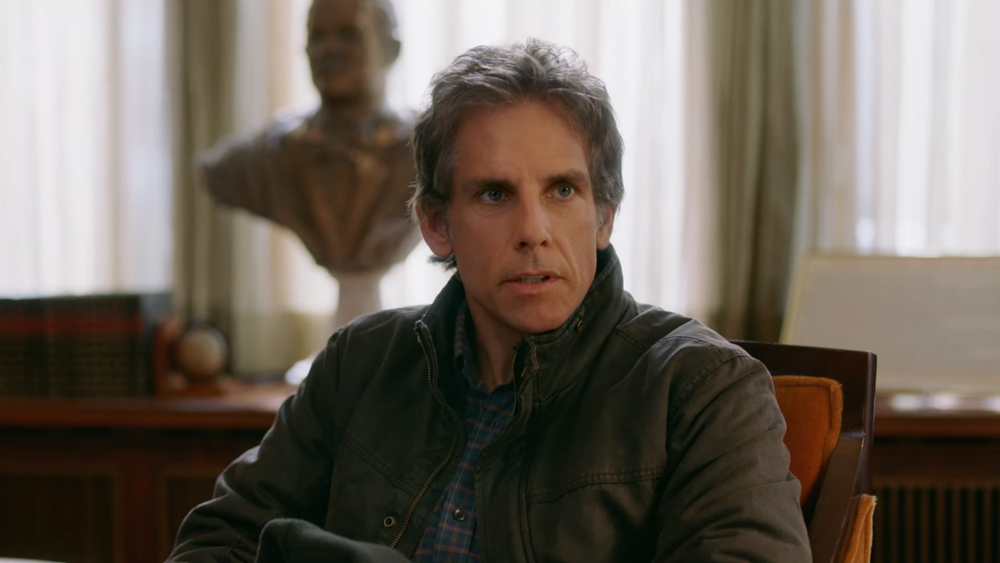

Brad (Ben Stiller) and his son, Troy (Austin Abrams), are out for the weekend scouting colleges. The kid thinks he has a good shot at Harvard. This scares the hell out of Brad. In his self-centered and astonishingly simplistic view, his son represents all the promise and energy of a bright future that he himself has squandered by living simply, settling down with a wife (Jenna Fischer) and child and dog, and running a nonprofit that helps other nonprofits raise money for their various causes. He looks back with rage and regret, spitting endless internal and external venom at his former college buddies who’ve all gone on to differing levels of fame and fortune (Jemaine Clement and Michael Sheen, struggling nobly with their American accents; Luke Wilson, who has one good scene and not much else to do; and White himself, as a film director … or an architect … the details here — and everywhere — are a little fuzzy, though sometimes by design).

As the film flashes endlessly through Brad’s psyche, we move backward and forward in time, glimpsing fantasy realities and always staying right there with Brad, seeing through his eyes and feeling the hurt of all the petty betrayals, both real and imagined, that he reminds us of relentlessly. The problem here is that the film seems to utterly loathe this character. We’re given zero reason to empathize with him at any moment, which, actually, might’ve worked just fine with a richer, more humanizing script. But the constant narration by Stiller undercuts every attempt at emotion the film tries to pile onto us. The film is a psychological travelogue of privileged insecurities that boil down to “I envy my friends.” Didn’t Stiller already make this movie about a dozen years ago? Did he think I forgot? I did not forget.

It’s not a bad movie. It’s just that it so obviously, easily could’ve been better. If White ends up blaming studio meddling for that narration, I’ll take it. But if this is really the version of this movie he wanted us to see, then that is an unsettling lack of self-awareness, to say the least.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.