For those of us who grew up in the 1960s and early 70s, The Ghoul (1933) was but a title and maybe a few stills (often mistakenly identifying Boris Karloff “as The Ghoul”). It was one of those legendary “lost” movies. The fact that it was a British picture had garnered little notice in the U.S. back in the 1930s, and there weren’t even the usual film buffs eager to tell you what they remembered from 30-plus years ago. In fact, the only one with anything of note to say was Karloff, who expressed the firm wish that it should remain lost. Obviously, he didn’t think much of it, but then to him it was just something he knocked out in England during a salary dispute with Universal. Otherwise, all we knew was that it had been “remade” in 1961 as What a Carve Up (No Place Like Homicide), a horror-comedy with no relation to anything the stills for The Ghoul suggested. (This may be because The Ghoul was based on a play by Dr. Frank King and Leonard Hines), while Carve Up was based on a novel by King. Both are called The Ghoul, but the stories are apparently different. Yes, it’s confusing.)

Sometime in the late 1960s or early 70s, a print of The Ghoul turned up in former Czechoslovakia. It was dark, censored, generally not in good shape and festooned with Czech subtitles. Somehow a copy of this print (with the subtitles clumsily blacked out) made its way to film historian William K. Everson — a man notoriously generous with his holdings, which meant his print eventually got copied and leaked onto the black market. It was pretty bad, but good enough to be intriguing. Sometime later a pristine negative was discovered in the England studio — in a largely forgotten vault that had been blocked by lumber for years. This copy — which only made its way to DVD in an official version in 2003 — not only restored all the missing footage, but was in such amazing shape it looked like a different movie altogether. Even if you’d seen the old Czech bootlegs, it was like seeing the movie for the first time — and it was a revelation that allowed The Ghoul to be seen as one of the classics of the “golden age” of horror.

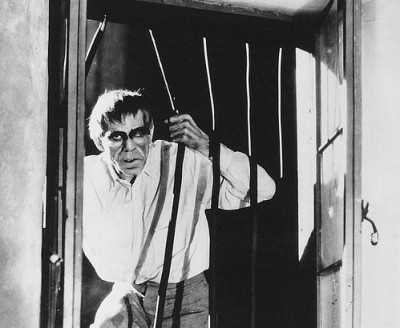

It also explained why Karloff was less that thrilled with the film. While Karloff was undoubtedly the star, the film didn’t give him more than a smattering of (admittedly rich) dialogue in the early scenes. He’s certainly good in the film, but — much like James Whale’s The Old Dark House (1932) — it isn’t really a star vehicle. In fact, he spends a great deal of the movie offscreen — something that the studio didn’t mind, I’m sure. They had what they wanted: a horror picture with Karloff’s name on it. That it didn’t do much for Karloff’s actorly ego does nothing to keep it from being one hell of a good film, which is pretty remarkable in itself.

To understand what a truly remarkable film The Ghoul is it helps to put it in context with other British movies of the era. By 1933 — actually by 1932 — Hollywood had worked out most of the kinks in sound film. Britain, on the other hand, seemed largely stuck with 1929 technology. The movies tended to be clunky, awkward and badly paced. Plus, sound recording was really primitive, especially where women’s voices were concerned. Only that last plagues The Ghoul — and only part of the time. The very first scene — with a landlady trying to get rid of what she thinks is a salesman (“We don’t want to buy no lino, nor nothing”) — briefly has that “this won’t travel well” feeling, but quickly rights itself to become creatively melodramatic. It helps that the film utilizes a very effective, nearly wall-to-wall, musical score. In that regard, it’s actually ahead of its Hollywood counterpart, which was still using music sparingly, if at all.

The story is a good one in the old dark house mode — in perhaps the oldest and darkest house ever. But it’s a little bit more than the usual in that it has an actual supernatural component — well, more or less. At the very end of the film there’s a line of dialogue that attempts to place everything we’ve seen in a realistic context, but it feels like a sop — possibly added after the fact — to the notoriously antsy British censor who very likely didn’t care for the idea of a walking dead man, especially one reanimated by “heathen” ancient Egyptian gods. And the truth is that one line of catalepsy twaddle hardly explains what we’ve seen — not the least of which is the apparent superhuman strength exhibited by the walking dead Karloff. It certainly does nothing to dispell the intensely creepy atmosphere the film has spent 70 minutes generating.

How The Ghoul came to be a great horror picture is a mystery. You can pore over the film’s credits all you like, but apart from the incredible cast — not just Karloff, but Ernest Thesiger, Cedric Hardwicke, Ralph Richardson (his film debut) and a surprisingly animated Anthony Bushell — there’s nothing to suggest this should be anything other than ordinary. The writers have no other claims on the genre and director T. Hayes Hunter is impossible to assess because none of his other films seem to be available. Looking over his credits suggests he had a film of this type in him. It is perhaps a happy series of accidents that led to the results here, but whatever the case, the film is richly melodramatic horror — with marvelous performances, a witty script, atmospheric direction and a surprising number of effective shocks — including a final scene for Karloff that may well be the grimmest and most startling moment in classic horror.

The Thursday Horror Picture Show will screen The Ghoul Thursday, June 13, at 8 p.m. in the Cinema Lounge of The Carolina Asheville and will be hosted by Xpress movie critics Ken Hanke and Justin Souther.

in a largely forgotten vault that had been blocked by lumber for years

Don’t you just hate (love) when that happens?

The irony is how well it was preserved in there — much better than so many titles in carefully controlled environments.