Matthew Warchus’ Pride may just be the year’s biggest surprise — and it’s almost certainly the biggest crowd-pleasing, uplifting movie you’ll see all year. I mean that in the best possible way. This is a movie that fully earns its every emotional pull and has the wisdom — and structure — to dole them out through the film with amazing canniness. What makes it even more amazing is that the film was written by a newcomer, Stephen Beresford, and directed by Matthew Warchus, whose only previous directorial credit is the little seen, badly reviewed Simpatico (1999) — and who is better known for his stage work. But as sometimes happens, Warchus appears to be one of those theater folks who sees film as a liberating force that allows for a flexibility that doesn’t exist on the stage. Certainly, there is nothing even slightly stagey to be found here, though a sense of theater is clearly present. Pride is full-on filmmaking from first to last.

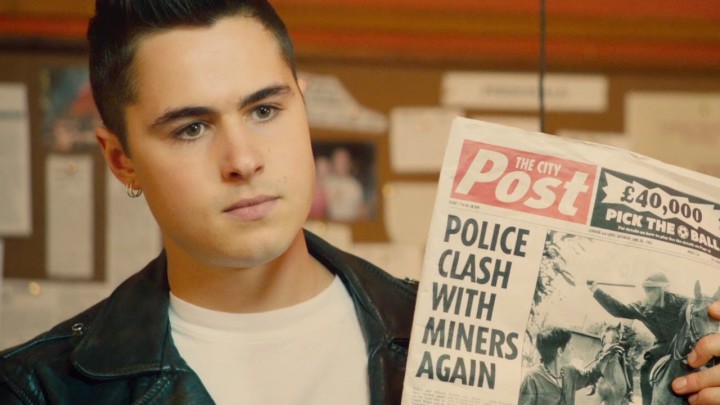

It’s a period piece — set during the miners’ strike of 1984 in Thatcher’s Britain — and is based on the true story of a group of gay activists working to help support the striking miners — despite the fact that the miners aren’t exactly thrilled by the prospect of throwing in their lot with gays. Aspects of it are likely to remind you of another fact-based film, Kinky Boots (2005), where a much-disdained transvestite (Chiwetel Ejiofor) helps to save a dying shoe factory. Actually, it reminded me of a friend of mine who worked for the British Film Institute and used to write film criticism for The Gay Times. He also had a keen interest in the history of black people in Great Britain but often faced resistance because of his sexual orientation. Much the same thing happens in Pride. In fact, as presented in the film, several miners’ groups turned the activists’ support down outright or wouldn’t return their calls — until one, mostly through misunderstanding who they were, opted to accept the money they raised. What they had not expected was that the activists would accept an invitation to come to the little Welsh mining town.

Yes, you can call the results of this visit — and the alliance that comes into being — fairly predictable. But it’s only predictable in broad strokes. Some things — the unswerving resistance of one faction — are surprising in the fact there is no “seeing the error of their ways” moment, which is refreshing. Other things — like guessing who the closeted gay in the mining community (you know there has to be one) will turn out to be — aren’t in the least surprising, but that doesn’t mean they don’t work. What keeps the film working for its entire two-hour running time is a perfect blend of cinematic and dramatic drive, a generosity of spirit and a wonderful ensemble cast.

That cast — and its ensemble nature — is worth considering, not in the least because this is not a star vehicle. Yes, Bill Nighy, Imelda Staunton, Dominic West and Paddy Considine get top billing — and they contribute greatly to the film (especially Dominic “God, I miss disco!” West) — but they can hardly be called the stars, just the biggest names. Relative unknowns like Ben Schnetzer, George MacKay and Andrew Scott probably have greater screen time, but even they are not really the stars. Rather, it’s the large cast of characters and performers taken as a whole who are the movie’s collective stars. And what stars they are. Rarely have I seen a film with this many characters that is never confusing and in which no one gets lost in the shuffle. It all comes together so beautifully that it’s frankly astounding. Yes, it’s a film that very deliberately sets out to hit all the right notes, but those right notes are so very right that it feels completely natural. You will be doing yourself a great disservice if you don’t see this charming, moving, funny film. Rated R for language and brief sexual content.

Do you consider this ensemble better than Grand Budapest Hotel?

I consider it different in that there very clearly is a star turn and a star character in Grand Budapest. Here, everyone seems to be on the same footing.

I found Andrew Scott’s performance in this particularly touching. Especially nice to see him giving such a restrained, subtle performance since I know him best from his wonderfully arch Professor Moriarty.

You have the advantage on me with the comparison.

Scott is also the voice in Locke that I (and others, I’ve since learned) thought was Chris O’Dowd.