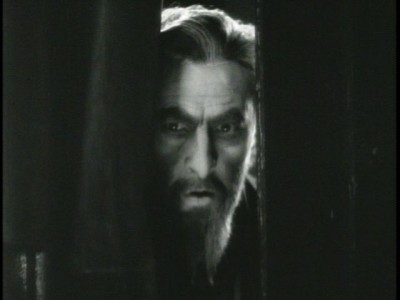

It’s actually something of a shame to categorize Svengali (1931) as a horror film (though it certainly qualifies as one), but too many people see the term and run the other way. It’s a horror film, indeed, but Svengali is more than a horror film. It’s a romantic fantasy, a dark comedy and a film with an ending that still surprises — and is both touching and satisfying. But beyond this — and the fact that it has some of the most marvelous production design and photography of its era — it has one of the great John Barrymore’s finest and most entertaining performances. Barrymore himself loved the role and took a hand in shaping the screenplay’s comedic content. Hating his matinee idol good looks, Barrymore took particular delight in roles that allowed him to adopt a grotesque character makeup — and the role of Svengali not only allowed him that, it offered him a character who reveled in his notable lack of hygiene. (Early in the film he’s asked when the last time was that he took a bath, and Svengali replies, “Not since I tripped and fell in the sewer.”)

The story is drawn from George DuMaurier’s popular and influential 1894 novel Trilby (it inspired Gaston Leroux to write The Phantom of the Opera), about an artists’ model, Trilby O’Farrell, who might be said to be overly friendly and accommodating. She has the misfortune of falling in love with a young — very proper, very upright — English painter called Little Billee, who has come to Paris to paint. At the same, there’s a Polish Jew music teacher, Svengali, who is in love with Trilby, and who, through hypnosis and mind control, turns the otherwise tone-deaf girl into a great singer. The novel is more complex than that, but that’s the part of the story that caught the public imagination — more so Svengali than the title character. It wasn’t long before adaptations started using his name as the title. By 1931, when the Barrymore film was made, there had been six or seven film versions (some early ones running one reel or less), but this one — with the focus wholly shifted to Svengali (well, Barrymore was the star, not Marian Marsh) — is the definitive one.

Though the film is very much in the mode of German Expressionist horror (the incredible sets of the earlier part of the film are clearly influenced by Caligari), at bottom it’s a tragic love story. Actually, it’s two tragic love stories, though it’s kind of hard to get too worked up over the plight of Little Billee (Bramwell Fletcher). For all his humorous perfidy, Svengali (Barrymore) is ultimately a sympathetic character. His villainy, however, is the first thing the movie establishes with Svengali driving a woman (Carmel Myers) to suicide because she’s left her husband for him without getting any money from the man. When his faithful servant Gecko (Luis Alberni) announces that the woman has been found in the river, Svengali merely notes, “But that is not possible in this weather.” His interest in Trilby seems at first to be purely a combination of art and carnality, it slowly becomes obvious that Svengali is deeply — and hopelessly — in love with the girl.

When Billee learns the truth about Trilby’s promiscuous nature — he finds her casually posing nude for a roomful of men — and has an attack of uprightness, Svengali seizes the chance. He carefully points out that her history (the scene ends with him counting off a list of men to whom she’s been “kind”) makes her an unsuitable candidate to be presented to Billee’s mother and convinces her to run away with him — to let him turn her into a great singer. The problem is that — much as Trilby can only sing under hypnotic control — she can only “love” Svengali in the same state. At one point, fed up with her rejection of him in favor of the memory of Billee, he goes to that extreme — only to push her away in disgust, saying, “It is only Svengali talking to himself.” How this will ultimately play out is totally unexpected — and unlike anything to be found in the horror films that surround it, giving it a freshness even 80-plus years later.

It’s difficult to be sure who to credit with the film’s incredible atmosphere. Though a thoroughly competent director, there’s nothing else in Archie Mayo’s filmography to suggest he was capable of Svengali. Of course, a lot of the credit goes to Anton Grot’s set design and Barney McGill’s cinematography, but designers and photographers do not as a rule decide how films are presented. The temptation — and it’s quite possibly valid — is to think that Barrymore had a great deal to do with the film being as it is. The sequence where Svengali telepathically calls Trilby to him from across Paris — a skillful blend of moving camera, models, and full-size action — is one of the most startling things to be found in the early sound era. Sure Grot and McGill made it possible and pulled it off, but someone came up with the idea — and I wouldn’t be surprised if Barrymore was the source.

The Thursday Horror Picture Show will screen Svengali Thursday, May 9 at 8 p.m. in the Cinema Lounge of The Carolina Asheville and will be hosted by Xpress movie critics Ken Hanke and Justin Souther.

McGill, Grot and Barrymore returned the next year in THE MAD GENIUS which was directed by Michael Curtiz (a much stronger director at the height of his expressionist period) and the results are remarkably the same. Grot was involved with DOCTOR X and MYSTERY OF THE WAX MUSEUM which are also similar although they are in color. Barrymore & McGill were not.

True to a point, but I’ve never heard of an art director hanging around telling the filmmaker how to move his camera or what angles to shoot from. Have you? (Leave Menzies out of this, since he’s a unique case.)

Damn! I was just about to name Menzies. Just out of curiosity, how do you account for the similar look of all 4 films(SVENGALI, MAD GENIUS, DOCTOR X, MYSTERY OF THE WAX MUSEUM for those joining us late).

Menzies goes into the rare position at the time of production designer, while I’m not even sure how much of Grot is Grot and how much is the art department he supervised. (Look at all the movies that are signed by Van Nest Polglase and how few he actually personally designed.)

My guess — and that’s all it is — is this film set the template. And let’s face it, Mad Genius — no matter how much I love it personally — is largely a cash-in on this. The real stumper, though, is why none of the others has anything like that fairy tale traveling shot from Barrymore to Marsh across the roofs of the model of Paris?