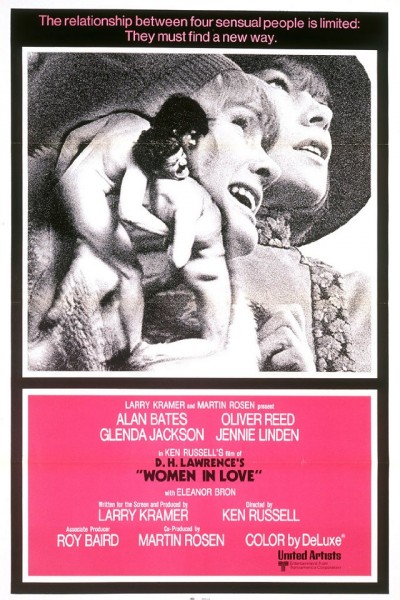

July 3 would have been Ken Russell’s 85th birthday and since this marks the first year I haven’t been able to call him for many years, the Asheville Film Society is screening his first international hit, Women in Love (1969). This is the film that won Glenda Jackson her first Best Actress Oscar—and scored nominations for Russell (director), Larry Kramer (screenwriter) and Billy Williams (cinematography). (That screenwriting nomination ought to have been for Kramer and Russell, but Russell’s name got left off the film by producer Kramer.) Those things, of course, are less what the film seems to be remembered for than the famous full-frontal nude wrestling match between Alan Bates and Oliver Reed. Nothing like it had been seen before in a mainstream film—and, for that matter, it’s not exactly common today. And in a way, that sensationalism is too bad, because there’s a lot more to the film than that one scene. But in another sense, it’s apt since no filmmaker’s career was ever as marked by controversy as that of Ken Russell.

Women in Love was the fourth Ken Russell picture I saw, and I wasn’t all that taken with it until I saw it a second time. My initial response—after having seen Tommy (1975), The Devils (1971), and Lisztomania (1975)—was that it was, more than anything, “the Ken Russell film for people who don’t like Ken Russell films.” There is some truth in that—mostly due to the film’s literary pedigree—but time and subsequent viewings have convinced me that it’s actually a great movie.

I’d certainly rank it in the top ten literary adaptations of all time. It’s that rarest of adaptations in that it captures the novel and comments on it at the same time. Russell has looked at the novel as a kind of autobiographical wish-fulfillment. The characters are Lawrence and his friends as he saw them—or maybe, as Russell once corrected me, “as he would have liked them to be.” As a result, the film is often as much about Lawrence as it is an adaptation of the book. Take the garden luncheon where Lawrence’s alter-ego Rupert Birkin (Alan Bates) embarassingly recites the poem “Figs”—a poem (equating the fig with female genitalia) by Lawrence that is not in the novel. But you almost feel it ought to have been after you’ve seen the film, because it pegs Birkin and Lawrence in a way the book sometimes struggles to do.

The title Women in Love is somewhat misleading (or ironic). Yes, the story is about the Brangwen sisters—Gudrun (Glenda Jackson) and Ursula (Jennie Linden)—being in love with, respectively, Gerald Crich (Oliver Reed) and Rupert Birkin. But it is as much or more about the relationship between the two men—something that becomes clear during the nude wrestling match and in many respects defines the film and Lawrence’s complex and sometimes conflicted views on male-to-male relationships. The film deals with Birkin’s (Lawrence’s) homosexual tendencies with astonishing complexity. Russell shoots the wrestling match in such a way that it looks like a romantic grappling as it increases in intensity (something underscored by the music being partly the same as that used in both Rupert’s tryst Ursula and Gerald’s coupling with Gudrun).

Of particular note, though, is that while it’s Rupert who follows the wrestling with his proposal of both spiritual and physical intimacy—something Gerald sidesteps by wanting to wait “until I understand it better”—it is Gerald alone who expresses any actual physical contact. Rupert’s very ability to clearly articulate his beliefs works against his ideas at every turn with Gerald. In an amazingly photographed later scene in a room with multiple mirrors, it happens again—with Gerald rejecting Rupert’s ideas by telling him, “I know you believe something like that, only I can’t feel it, do you see?” When it finally comes to the climax of their relationship late in the film with Rupert reminding Gerald, “I’ve loved you as well as Gudrun. Don’t forget,” he’s shot down with the most chilling words in the film, “Have you? Or do you think you have?” In the end, it seems Rupert has talked—or intellectualized—himself out of the very relationship he wanted.

Interestingly, at the time he made the film, Russell more or less sided with those—especially Ursula—who rejected the possibility of having the “two kinds of love” Rupert/Lawrence was searching for. This is made very clear in the film’s final scene. On the one hand, Russell filmed the scene exactly as it appears in the novel, but his choice of the final—extremely powerful—image makes his response to the material clearly at odds with Lawrence’s beliefs. (It should be noted that this is part and parcel of a central Russellian concern about the stronger—usually male—personality in a relationship overpowering and even thwarting the weaker.) Years later, he became less certain that he wasn’t really more in line with Lawrence than he had originally thought.

The Asheville Film Society will screen Women in Love Tuesday, July 3 at 8 p.m. in the Cinema Lounge of The Carolina Asheville and will be hosted by Xpress movie critics Ken Hanke and Justin Souther.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.