Buncombe County struggles with a high suicide rate, and though old wives’ tales say that letting someone talk about killing themself will make them more likely to do it, local health experts disagree.

“That is not true. It’s actually the opposite,” says Sue Brooks, executive director of All Souls Counseling Center at 35 Arlington St. in Asheville. “The more they discuss it and look at options, the more likely they are to be safe and not to be impulsive and take their own life.”

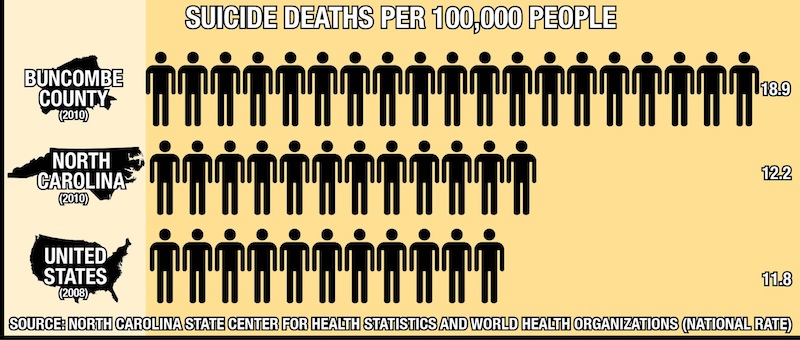

In 2010, there were about 19 suicides per 100,000 deaths in Buncombe County, according to the North Carolina State Center for Health Statistics; the state average was about 12 per 100,000.

Asheville's reputation as a progressive, eccentric community could contribute to the county’s higher suicide rate, suggests Cliff Rubin, executive director of the Listening Heart Crisis Center.

“Eclectic people tend to be on the outskirts of society, and thus they're already not normalized,” explains Rubin, whose group runs the local suicide crisis line (see box, “Where to Turn”). “This area certainly has a higher level of eclectic than any other part of North Carolina, and so that is going to attract people who are also on the edges of being comfortable with themselves, and the services are just not here to support them.”

In 2010, Buncombe County had the fourth highest number of suicides in North Carolina, after Mecklenburg (99), Wake (71) and Cumberland (46) counties, according to the State Center for Health Statistics. During that year, five times as many Buncombe County residents died from suicide (45) as from homicide (9).

In the two years since Rubin launched Listening Heart, they've taken 6,000 phone calls and intervened on 24 imminent suicides. He says the hot line stops depressed and mentally ill people from feeling alone.

“You can be depressed but not suicidal, but if you're suicidal you not only feel depressed but isolated — even if you're the one who isolated yourself,” notes Rubin. “That's the problem: if you feel isolated, with no place to turn.”

All Souls Counseling Center also tries to intervene before people become suicidal and/or must be hospitalized. The nonprofit offers the uninsured and underinsured discounted rates on counseling for mental illnesses including depression, anxiety, postpartum depression, post-traumatic stress disorder and bipolar disorder.

“When someone gets the help they need — before it gets to the point where they cannot function at work, being a parent, being a student, or just being a part of life — there’s a very good chance they won't ever get that serious about suicide,” Brooks reports.

Stigma concerning mental health care may deter some county residents from seeking help, she reveals, adding that attitudes are beginning to shift.

“People are more and more realizing we cannot separate our physical body and our mental and spiritual body: It all goes together,” says Brooks. “To ignore what we may be feeling and what may be going on in us mentally is to ignore our overall health. Unfortunately there are still some cultures that are not as accepting of mental health treatment, or of people getting the help they need.”

Brooks believes the key to decreasing the number of suicides in Buncombe County is encouraging people to ignore the stigma. “We need to get more information to the community that not only is it OK to seek mental health services, it is truly wise and important to do so,” she asserts.

Disagreement in the community about the most effective strategies for suicide prevention constitutes another local roadblock, Rubin says. And while he says he feels proud about “saving lives and helping people find the help they need,” he takes exception to criticism that the hot line uses volunteers rather than licensed professionals.

“We are an extremely inexpensive way that could be used to reach a lot of different people, and yet we've run into a lot of flack because we're peer volunteers — like that isn't useful,” Rubin declares. “I think it's tremendously useful, and it's proven to be. We haven't had a single suicide go south on us yet.”

The volunteers must complete 30 to 40 hours of training before taking phone calls, and Rubin says many don't finish the program. “The training is so hefty our graduation rate is only three out of five,” he reveals. “Some people can't make it through, but that's better than them making it through unprepared.”

Critics have also cited the fact that Rubin isn’t a physician, though he points out that Listening Heart does have a clinical psychologist on staff. Rubin plans to leave the Asheville area soon, and he hopes his replacement will at least have a master’s in social work, which he feels would help the nonprofit raise money.

Still, despite the controversy, Rubin believes Listening Heart provides “a bridge of compassion” to those in need, keeping in mind that anyone could find themself in that position.

“The difference between success and non-success is a single choice that snowballs on itself,” he says. “For some people, they don't even feel they have a choice.”

— Freelance writer Megan Dombroski lives in Asheville.

I’m very surprised that Mobile Crisis Management (MCM) is not listed in your article or in the “Need Help?” section. MCM takes calls from people that are in crisis and may be a danger to themselves or others, and will actually respond to the individual wherever they are located. MCM provides crisis and safety planning as well as assistance obtaining medical and psychiatric services as needed. There is no cost to the caller for the service. MCM serves Buncombe, Henderson, Madison, Mitchell, Polk, Rutherford, Transylvania and Yancey counties.

Please, Mountain X, help your readers become aware of this service.

Mobile Crisis Management can be contacted by dialing 1-888-573-1006.