|

Tunnel Road has seen its share of change over the years. But there’s one long-running business that seems untouched by time: The Mountaineer Inn, one of the cheaper motels on the strip leading east from the tunnel to the Asheville Mall.

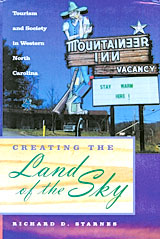

The neon sign, erected in the 1950s, depicts a barefoot, threadbare hillbilly with a corncob pipe in one hand and a rifle in the other. A quirky local landmark of sorts, it’s become such a staple of the landscape that many folks who pass by no longer even see it.

But Asheville native Richard D. Starnes, an assistant professor of history at Western Carolina University, has taken a good, hard look at the sign. And in his new book, Creating the Land of the Sky: Tourism and Society in Western North Carolina (University of Alabama Press, 2005), Starnes sees the neon mountaineer as both a conflicted cultural icon and a fitting symbol of what he calls “the defining force in western North Carolina”: tourism.

“Although portrayed as backward, ignorant, and prone to violence, mountaineers conversely enjoyed a reputation for hospitality, quaintness, and traditional values,” writes Starnes. “Despite his intimidating appearance, this mountaineer welcomes outsiders and invites them to share both his region and his leisurely lifestyle for a time and a price. This use of an essentially negative cultural image by locally owned businesses to attract tourists suggests the complicated relationship between tourism and culture in western North Carolina.”

A photo of the Mountaineer sign graces the cover of Starnes’ book. And though the author doesn’t expend many pages on it, he does make it a credible emblem of his story, which is as embedded with contradictions as the popular image of the wily mountain dweller.

The book traces the development of tourism as WNC’s economic engine from 1800 to the present, with a focus on the century or so following the Civil War. By the mid-19th century, several popular getaways for mostly Southern elites had sprung up in and around Asheville, generally centered around either choice mountain vistas or rivers and springs. Such locales, as one contemporary writer put it, attracted “the fashionable and sickly people from all the Southern States.” Wealthy Northerners also took a shine to the area soon thereafter — the most famous, of course, being George W. Vanderbilt, who created Biltmore Estate in the 1890s, bringing the region a flood of national attention.

That’s also when Asheville began to develop something of a reputation for being part of, yet in many ways distinct from, the rest of WNC. “In fact, travelers often wrote of antebellum mountain resorts as if they were islands of progress in a sea of primitive squalor,” Starnes observes. In 1875, travel writer Frances Fisher Tiernan wrote “The Land of the Sky” or Adventures in Mountain By-Ways under the pen name Christian Reid; Starnes credits the book both with coining the “Land of the Sky” moniker and with shaping nationwide attitudes about the allure of our mountains. In the novel, four young Victorians summering in Western North Carolina are wowed by the region’s natural beauty. Impressed with relatively cosmopolitan Asheville, they’re dismissive of the residents of more rural areas nearby. “Mountaineers lived beyond the tourist’s concept of civilization,” Starnes notes.

Asheville’s separation from its neighbors is one of many tensions that animate this history. Another key one: A place could draw “the fashionable and sickly” for only so long; at some point, local leaders feared, the fashionable would begin to fear the sickly. By the early 1900s — just as the area’s reputation was peaking as a place to get well by imbibing cool spring water and crisp mountain breezes — advertisements for Asheville boarding houses began to include such admonitions as “no consumptives” and “well people only.” At the same time, local boosters began a concerted campaign to replace “health tourism” with the picturesque variety, stressing the mountains’ unspoiled natural splendor.

But for all the drawing power of scenic tourism, many locals preferred to emphasize other economic strategies for the region, such as exploiting its natural resources. Starnes makes this clear in a detailed discussion of the debate that raged over the creation of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. While Asheville business people largely favored the idea, “leaders in counties further west were less sure of staking the region’s economic future to tourism in the form of a large, untaxable, undevelopable national park,” he writes. Understandably, lumber and paper companies were among the project’s fiercest opponents (as were more than a few of the mountain families who would be displaced). Nonetheless, in 1930, the park was officially established. Within a decade, it was drawing more than a million visitors per year.

Throughout his history, Starnes finds that while WNC has actively courted tourists and benefited from the billions of dollars they’ve spent here, the region’s residents have never lost their aversion to outsiders. The tourist as menace to local society was a characterization sounded as far back as 1916, when Asheville Police Chief L.E. Perry complained that the town “has a criminal element which is in numbers out of all proportion to the permanent population. … The mere fact Asheville is a tourist town attracts here each year a large number of professional crooks — gamblers, confidence men, ect. [sic] — who come to ply their trade among the pleasure-seekers.”

Today, of course, we hear more complaints about skyrocketing real-estate costs and gentrification than about tourist-targeting grifters. And looking beyond the region’s economic health, Starnes writes, tourism also “has pronounced social and cultural implications that, when combined with its economic importance, define society in western North Carolina.” If the past he documents is any guide to our present and future, tourism’s pros and cons will continue to shape the lives of those who live here both in and out of tourist season.

A recent development could provide a clue to the direction that influence may take. In October 2005, the Buncombe County Tourism Development Authority adopted a new slogan — replacing the chestnut “Land of the Sky” with “Any Way You Like It.” And though historians are sometimes loath to comment on current events, Starnes was forthcoming in his assessment of WNC’s latest catch phrase. “The new slogan represents the quest to better appeal to tourists in a more competitive marketplace,” he told Xpress. “But the landscape has always been the primary attraction, and to sever the land from the promotion of the region strikes me as hollow. It sounds too Las Vegas to me.”

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.