Teachers and employees at schools across two Buncombe school districts say they can’t afford to live and do what they love in Buncombe County: Teach kids.

Stresses from increasing costs of living and lagging pay have educators working multiple jobs, renting out rooms in their homes and relying on food banks, negatively affecting their classroom proficiency.

“If I don’t have the resources I need, I can’t do [the kids] justice. It’s impossible. I’ve tried to twist myself and do educational yoga for the last 20 years. And I can only do it so much longer,” says Matthew Leggat, a sixth-grade teacher at Montford North Star Academy.

Pay for educators comes from two major funding sources. The state sets base pay for both teachers, or certified staff, and other school employees like custodians, bus drivers and noncertified instructional assistants, or classified staff.

Then, each school district has the option of adding supplemental pay to account for the higher cost of living in certain parts of the state.

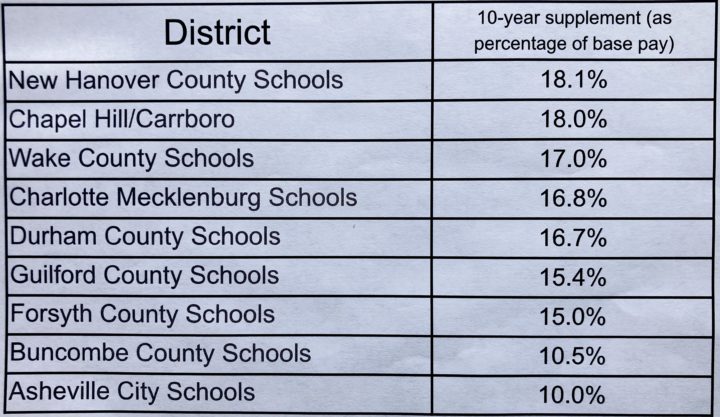

A 10-year teacher in Asheville City Schools and Buncombe County Schools makes less than those in eight comparable districts in North Carolina while having the highest cost of living in the state, according to the Virginia-based Council of Community Economic Research.

For months, dozens of teachers and employees have lobbied BCS and ACS to raise the local supplements for all staff, and both boards of education approved budget proposals that largely met those demands.

But school districts don’t have taxing authority, so the Buncombe County Board of Commissioners will ultimately decide what percentage of local tax dollars — primarily from property taxes — gets allocated.

In a budget proposal presented by County Manager Avril Pinder on May 16, both school districts are in line to get an increased allotment, but far less than what they requested.

ACS interim Superintendent James Causby requested $20 million, which includes a request to raise property taxes from 10.62 cents to 12 cents per $100 of property value. The county’s proposed budget does not raise taxes and slates $16.8 million for ACS.

BCS is projected to get $90.3 million of its requested $116 million, according to the county’s proposed budget.

Teacher advocates have lobbied for a 7% bump in the supplement for teachers and a 20% raise or living wage for classified staff, whichever is greater.

Currently, a first-year teacher in North Carolina makes a base pay of $37,000 a year, and after supplements from BCS or ACS, a starting teacher in either school district makes just over $40,000 per year.

Local nonprofit Just Economics calculated the living wage for Buncombe County in 2023 at $20.10 per hour, which equates to about $41,800 per year, says Eric Smythers, living wage program coordinator for Just Economics.

“Our students deserve fully staffed classrooms with educators who are able to focus on their work, not educators who are tired from working two or three jobs and worried about putting food on the table,” says Shanna Peele, president of the Buncombe County Association of Educators.

Lissa Pederson, a 12-year elementary art teacher and vice president of the BCAE, says the respect she would feel from making an amount of money comparable to jobs with similar experience and education would make a huge difference in her ability to foster a quality teaching environment.

“You feel respected. You can afford your lunch. You can afford your rent or your mortgage. And it’s also that your mind isn’t wandering to ‘Should I go?’”

Supplement skew

BCS Chief Financial Officer Tina Thorpe often touts Buncombe’s sixth-highest average supplement, $8,292, as evidence of its relative success in paying teachers well compared with other districts.

David Honea, math teacher and cross-country coach at A.C. Reynolds High School, says that number, reported on the N.C. Department of Public Instruction’s database, is misleading because it is skewed by the large number of veteran teachers with National Board for Professional Teaching Standards certifications, which qualify them for higher pay.

The only teachers who make that supplement have at least 25 years on their teaching license, a master’s degree and national board certifications, or 30-plus years of experience.

According to data provided by BCS spokesperson Stacia Harris, 86% of teachers for BCS have less than 25 years of experience, and 95% have less than 30 years of experience.

Honea says it is frustrating that Thorpe has presented the supplement average to decision-makers as illustrating where Buncombe stands compared to other districts, while a majority of teachers make far less than that.

That’s why BCAE prefers comparing supplements as a snapshot in time, like for a teacher with a bachelor’s degree and 10 years of experience, says Joan Hoffman, a veteran teacher at A.C. Reynolds High School who is an active member of BCAE.

Multiple Jobs

Kim Martin, lead American Sign Language interpreter for BCS, says at one point she had seven jobs to make ends meet for her and her four children, from catering on the weekends and cutting hair in her dining room, to working as a freelance interpreter at local colleges and renting out various rooms in her house.

“I think we’re all exhausted. Like, you know, trying to make ends meet. So, we’re not at our best when we’re coming to work,” Martin says.

Things were so tight at times that when her four children all lived at home, Martin made weekly trips to local food banks to make sure everyone got fed, she says. That made her feel disrespected.

“It’s hard to feel valued as an employee. And it’s hard to feel like the kids are valued,” she says.

After a raise in 2022, Martin now makes $19 per hour for a job that requires multiple certifications and continuing education. That’s not nearly enough to retain quality interpreters, who often make $50-$60 an hour as contracted freelancers in the private sector, she says.

That pay discrepancy means BCS has to recruit and pay freelance interpreters, who not only cost much more but also aren’t as experienced in working with children. Martin is proposing a pay raise for interpreters to $25 per hour, the national average for educational interpreters, which she says will save the district $10,000 a month.

“[Low pay] leads to bad morale among the staff, and the staff has just been leaving left and right. So thus, we have all the contract interpreters,” she says.

Should I stay, or should I go?

Hoffman says many teachers and staff often think about leaving, if they haven’t already.

She says she’s talked to multiple teachers who have a weekly debate with their families about whether it is still worth it to do what they love doing. Some have decided that it’s not, she says, and those who leave are hard to replace.

Kensley Herbst, a teacher at Isaac Dickson Elementary, says she narrowly escaped having to move back to Florida to live with her mom after she didn’t qualify for a studio apartment last summer on her teacher salary. She picked up extra jobs as a tutor and worked the front desk at an after-school program to qualify.

If staff retention is difficult, says Natalie Romanello, English as a second language teacher at Valley Springs Middle School, recruitment is just as tough, especially for teacher assistants. She says in her four years in Buncombe, she’s had an assistant only a quarter of the time.

“There’s really no great way to recruit people to this area. That’s how a lot of us feel,” she says.

Those instructional assistants, as well as other classified staff, are vital for student success, says Abbey Hessling, English as a second language teacher at Clyde A. Erwin High School.

“These people that are not being paid a living wage are doing some of the toughest jobs in our schools. They’re the ones who make it possible for us to teach and be in the classroom while they attend to the toiletry needs of our students,” she says. “They provide students one-on-one services that allow our most vulnerable students to be in the classroom. They drive our buses; they are custodians. And all of these people could be making better money in the private sector. But we rely on them to run our schools every single day and we need them there. Our students deserve professionals who can afford to make this their career.”

Honea says he’s doing OK as a 22-year veteran with a master’s degree for which he is paid extra, but it’s very hard to recruit teachers and coaches to help him build a program when other districts pay better.

North Carolina stopped paying a higher rate for teachers who began pursuing a master’s degree after 2013.

Additionally, coaches are paid a lump sum per season worked, which usually works out to below minimum wage after practices, games, tournaments and driving the team bus is considered. Honea says he makes less as a coach now than he did 20 years ago in Wake County.

“Teachers who need to supplement their teaching income can’t afford to take these [low-paying] positions. And those who don’t need the money have to ask if they can justify the time away from family when the end-of-season check is so small, they don’t even notice it. When I look to the future, even if I stay here, I don’t know how to convince a talented coach to come work with me.”

That being said, Honea, like so many others that have spoken publicly about issues surrounding teacher pay, says he has no intention of changing jobs.

“I love everything that I do. And I plan to do this work for at least another 20 years. But when I look ahead, I have to ask if I can responsibly plan to do that in Buncombe County,” he says.

More, but not enough

Despite the support from both local school boards, it appears the county Board of Commissioners will not support schools to the same degree.

It’s unclear exactly what cuts will be made from school district proposals if the proposed county budget passes. Those budgets will bounce back to school district staff to rework.

Hoffman says she understands that cuts happen in a budgeting process, but from a teacher’s perspective, the last place cuts should happen is in personnel that work with students.

“I mean, the state gives [the districts] all kinds of unfunded mandates. I get that. Sure. But that’s what the County Commission is there for, to step in and make up that money. I mean, yeah, that’s why we levy taxes and all those things. Right?”

Education advocates now turn their attention to the Buncombe County Board of Commissioners, which holds a public hearing on the budget Tuesday, June 6, before holding a vote Wednesday, June 21.

“We’re going to show up on June 6, and we’re going to make the same impassioned plea. Take care of us the way we take care of the students we serve. And understand that we understand that while we serve you, you serve us.” says Tate Macqueen, teacher and coach at Erwin High School.

Until NC teachers vote to shut down the NCAE, I have zero problems with their pay…dock their pay if they belong to NCAE.