Breathe in and exhale. We all have to breathe to live, and the good news is that here in Western North Carolina, the quality of the air we all share is much better than it was just a few years ago. Across North Carolina, government employees are monitoring air quality and the associated health risks to make sure they stay within specified legal parameters. Meanwhile, citizen volunteers are also collecting data and working to make more information available to the public.

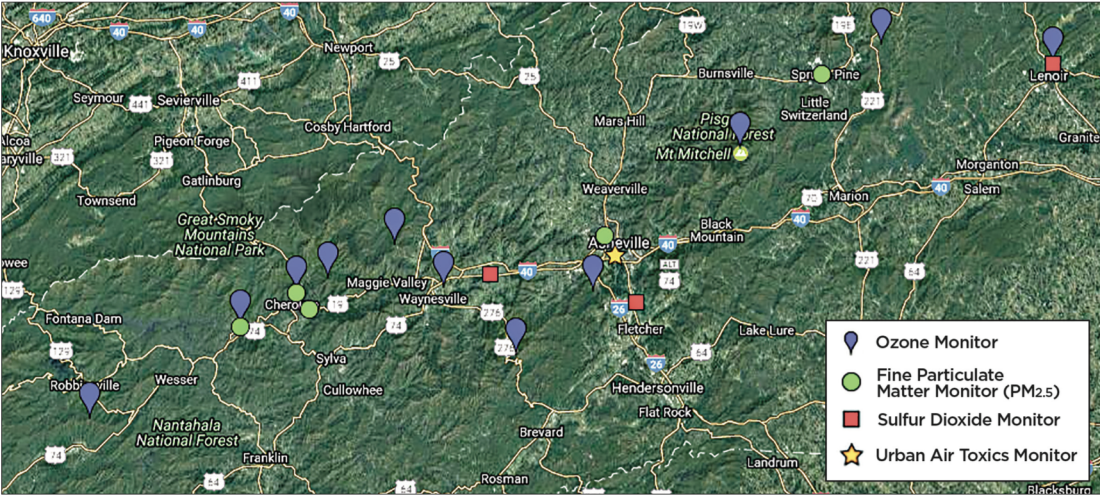

Eleven ozone monitoring sites stretch across WNC, from Bryson City to Lenoir, with Buncombe (at Bent Creek), Catawba, Mitchell and Swain county sites in between. Buncombe County also hosts one of five regional fine particulate monitors at the Board of Education building on Bingham Road.

Most of those devices are operated by the state Division of Air Quality, an arm of the Department of Environmental Quality. But three counties, including Buncombe, have their own local air agencies that oversee monitoring and related air-quality issues.

In North Carolina, the monitoring is mostly concerned with two things: ozone and fine particulate matter, says Brendan Davey, regional supervisor for the Asheville office. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has also set safety standards for four other air pollutants: carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide and lead.

Fine particulate matter refers to particles 2.5 microns or less that are present in ground-level air. They disperse light, creating hazy conditions and reduced visibility, as well as presenting a health risk. Much of that pollution is sulfate-based and comes from burning fossil fuels, especially coal, Davey explains.

Volatile organic compounds are released by burning pretty much anything containing carbon, whether it’s wood, gasoline or the fumes from paint or solvents. When exposed to heat (such as sunlight), VOCs in the air react with nitrogen oxides produced by vehicles, power plants and factories to make ozone.

In the ozone

When two oxygen molecules are bonded, the human respiratory system loves it. Our lungs grab that O2 and send it over to the heart, from where it makes its way into the bloodstream for delivery to organs and muscles. But when a third oxygen molecule combines with the first two in the atmosphere, it makes ozone.

This pungent, toxic gas irritates the lungs and eyes, causes shortness of breath and is particularly harmful to the very young, the elderly, the infirm and those with chronic respiratory problems such as asthma. The air-quality forecasts issued by the Department of Environmental Quality distinguish hazard levels ranging from “yellow,” which would probably affect only those most sensitive groups, to “orange, red and purple,” which could have broader health impacts.

Particularly in rural regions, though, the readings for fine particulate matter and ozone don’t usually vary that much from one county to another, so they can be efficiently and effectively tracked with monitors spread out across a wider area, notes Davey. “At an instantaneous value, you’re going to get variability within small regions, depending on whether a diesel truck is driving by or things like that. … But the averaging periods we’re looking at get so large that it doesn’t look like it’s varying a whole lot from valley to valley,” he explains.

However, beautiful old mountains covered with lush forests do produce lots of VOCs — in fact, 90 percent of the volatile organic compounds present in the air in WNC are naturally occurring, according to the DEQ. Therefore, says Davey, “Controlling that type of pollution won’t have a whole lot of effect on our ozone concentrations. That’s why we’ve focused on nitrogen oxide emissions over the years.”

Temperature inversions

Meanwhile, where there are mountains, there are also valleys, and that means you’ll get temperature inversions, says Kevin Lance, field services program manager for the WNC Regional Air Quality Agency. Inversions happen when cooler air is trapped beneath a layer of warmer air. And as a result, the locally generated toxins and pollutants just sit there — a perfect recipe for reduced visibility and increased ground-level ozone. At lower elevations, such as in Asheville, the lion’s share of pollution comes from local sources such as traffic and industry, so the ozone readings tend to be worst in the afternoon.

This is the only area of the state where there are separate forecasts for the higher elevations and the valleys. Asheville, says Lance, is “situated kind of in a bowl,” so it’s subject to bad inversions. This was a much greater problem in the 1990s, before tighter restrictions reduced the pollution from coal-burning power plants. A 1999 National Park Service report titled “Clearing the Air at Great Smoky Mountains National Park” found that visibility in the Smokies had declined from 93 miles to between 24 and 36 miles.

Those special circumstances, Lance explains, are part of why it was deemed necessary to create a local air-quality agency several decades ago — around the same time the EPA was established. Another motive, he notes, was “being able to have some local input into the regulations.”

But ironically, says Davey, higher elevation monitors tend to record higher ozone readings because it blows in from other areas. And since those levels often peak in the middle of the night, you could be camping in the mountains yet breathing some of the lowest-quality air in the area at that particular moment.

Clearing the air

In other ways, however, WNC is well-positioned for clean air. The region isn’t heavily industrialized, and it doesn’t have the kind of large-scale pig or poultry farms that generate a great deal of pollution in other parts of the state.

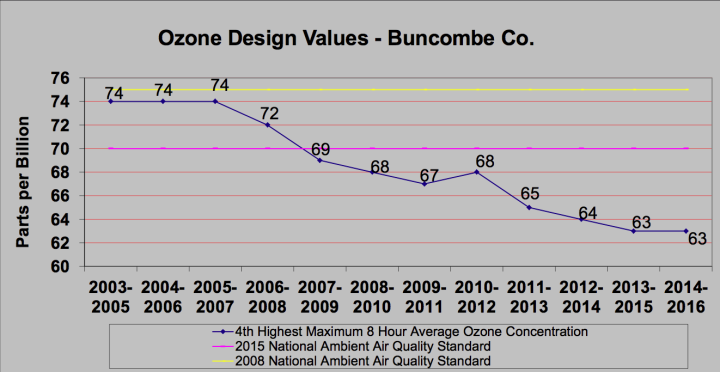

The EPA’s limit for ozone is 70 parts per billion. Using a complex formula, the agency averages readings taken over specified periods of hours, days and years. If the resulting figure is at or below the EPA standard, the area is considered to be in attainment. Fine particulate monitoring is done in a similar fashion.

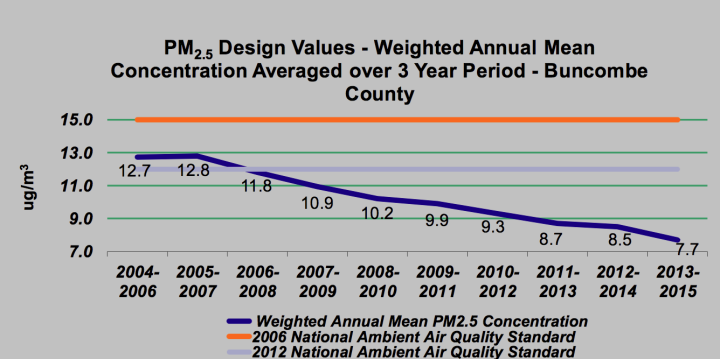

EPA air-quality standards have gotten significantly more stringent since their inception, and overall air quality, says Davey, has improved nationwide. North Carolina, he notes, has met or bettered the EPA standards for both ozone and fine particulates. After the General Assembly passed the Clean Smokestacks Act in 2002, he explains, “Power plants started doing some early reductions of sulfates and nitrogen oxides. And that helped North Carolina lead the way in the Southeast in staying ahead of [EPA] standards as they were being reduced.”

Since then, WNC’s ozone and fine particulate levels have dropped significantly. The improved ozone levels, says Davey, are largely due to reduced nitrogen oxide emissions “from the power plants and factories, and cars being cleaner over the years.”

Citizen monitoring

Notwithstanding the substantial progress that’s been made, more needs to be done, says Clean Air Carolina, a Charlotte-based nonprofit. AirKeepers, a pilot program launched in Mecklenburg County last year, enlists volunteers to monitor what it calls “hyperlocal” levels of fine particle pollution. A training curriculum that’s now under development will streamline and standardize the learning curve, teaching people how to use the sensors properly and understand which data are significant. In the meantime, the program is working with the EPA to compare the data it’s collected so far with official data from the government’s stationary monitors, and to determine the accuracy of the hand-held sensors the nonprofit is using.

One big goal for this year, says program director Terry Lansdell, is expanding the nonprofit’s operations across the state, particularly in Raleigh and Asheville, to supplement the existing monitors. By the end of this summer, he notes, they hope to have finished validating their data-collection methods and be ready to start working in Asheville and other areas where they can partner with schools, prioritizing places with insufficient monitoring. “Asheville is a critical need area,” he explains, “because there’s just not enough monitoring to fully understand the impact air quality has.”

The government agencies do a good job, stresses Lansdell, but there aren’t enough monitors, and they provide only limited snapshots of air-quality conditions. “When we have a monitor working 24/7,” he points out, “we’re able to capture pollution events that may not be part of the monitoring requirements.” That additional information, Lansdell maintains, is valuable “for people who are more interested in understanding what the air is like right now rather than what it’s forecasted to be tomorrow.”

Pros and cons

That kind of citizen involvement could be valuable in certain situations, such as last year’s wildfires, says Lance of the WNC Regional Air Quality Agency. “If you have an event like that, that’s going to vary a great deal based on the topography here. It’s harder to predict because of the mountains.” In such cases, he points out, a hand-held particulate sensor might enable citizens to make better real-time decisions.

But in general, Lance believes the current monitoring system is adequate, and he has doubts about the accuracy and usefulness of the kinds of sensors sold to consumers, especially in the hands of amateurs. Those devices, he says, “are not as reliable, and that kind of concerns me. You know, if they’re getting readings that alarm them, they’re going to be calling us” — at which point the agency would have to refer to its own data anyway.

Lori Cherry, environmental program consultant for the Division of Air Quality, shares those concerns. Although she respects the intentions of groups like AirKeepers, Cherry says her agency tested several high-end, off-the-shelf sensors, and the results were not encouraging. “We would compare that same sensor to regulatory monitors, and there was no comparison: The data just didn’t match at all.”

Down the road, she continues, such devices could be helpful, because “they’re not very expensive, they’re portable, and it doesn’t require a lot to understand how to use them.” But she’s not convinced that the technology is sophisticated enough yet. It might be able to tell a jogger to get off a main road to avoid tailpipe emissions, but it can’t support broader conclusions about what those tailpipes might be doing on a larger scale. “They’re helpful for making personal decisions,” says Cherry, “but they’re really not helpful for monitoring the air.”

In the meantime, though, notes Lansdell, there are various kinds of organizations that might find these devices useful in their current form. For example, they could tell a day care center “what the exact air quality is at 2 o’clock, when they’re wanting to go outside for recess. That may be different from the forecasted levels.”

He also sees these sensors as a powerful public health tool that could help hospitals, health departments and other agencies track health incidents and correlate them with localized air-quality problems. In addition, says Lansdell, people with asthma or other lung diseases “can use these monitors at home … to help them understand how the air is outside and whether they want to go for a walk or a bike ride or need to stay inside to protect their health.”

Together, these efforts are a breath of fresh air for WNC residents and visitors alike, supporting the region’s tourism industry while laying the groundwork for improved public health and quality of life.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.