- photo by Tom Burnet

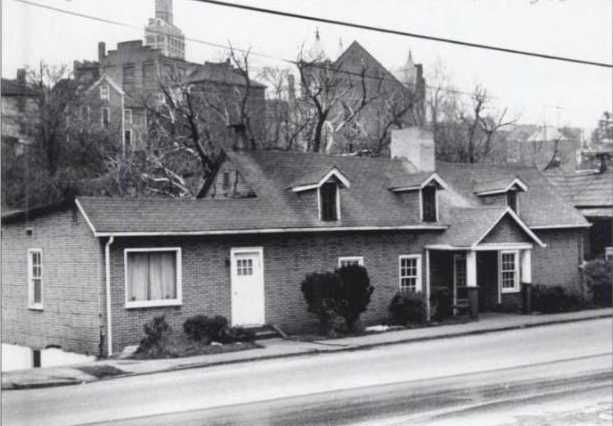

- Demolished: Isaac Dickson’s home on Valley Street, torn down in the 1960s to make way for urban renewal. photo courtesy of Pack Memorial Library’s N.C. collection

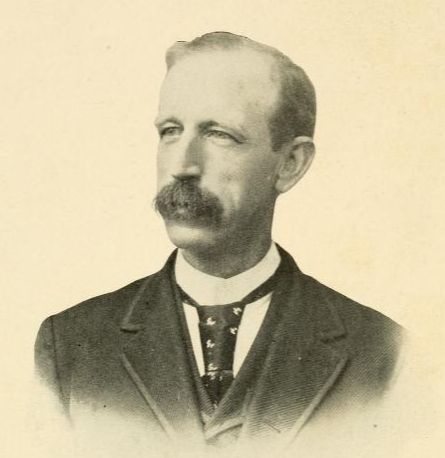

- Black and white: Thomas Walton Patton, a Confederate captain and slave owner, donated the land for Trinity Chapel. His former slave quarters later became Dicksontown. photo from 1908 pamphlet Thomas Walton Patton: A Biographical Sketch

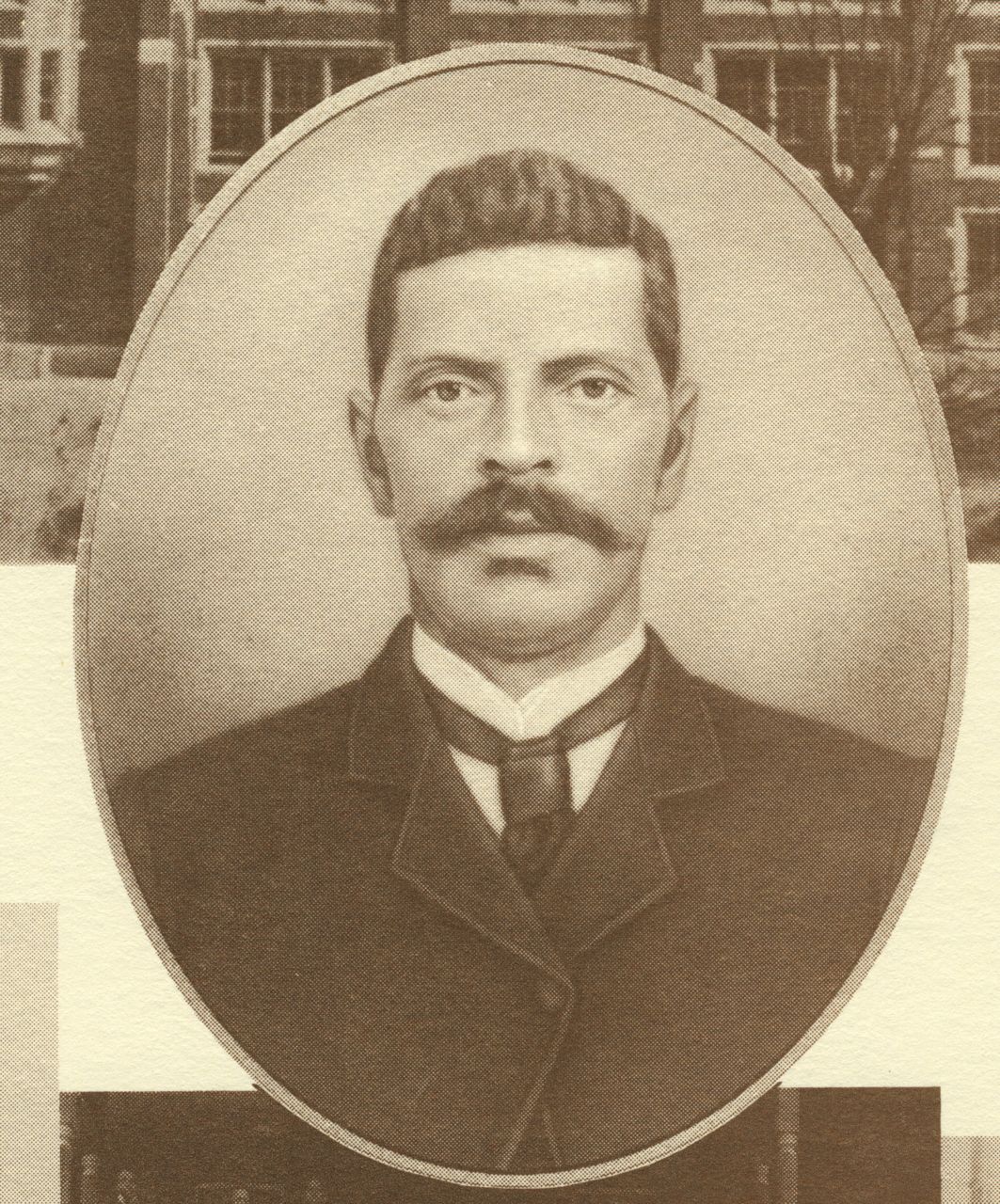

- Isaac Dickson photo courtesy UNCA Special Collections

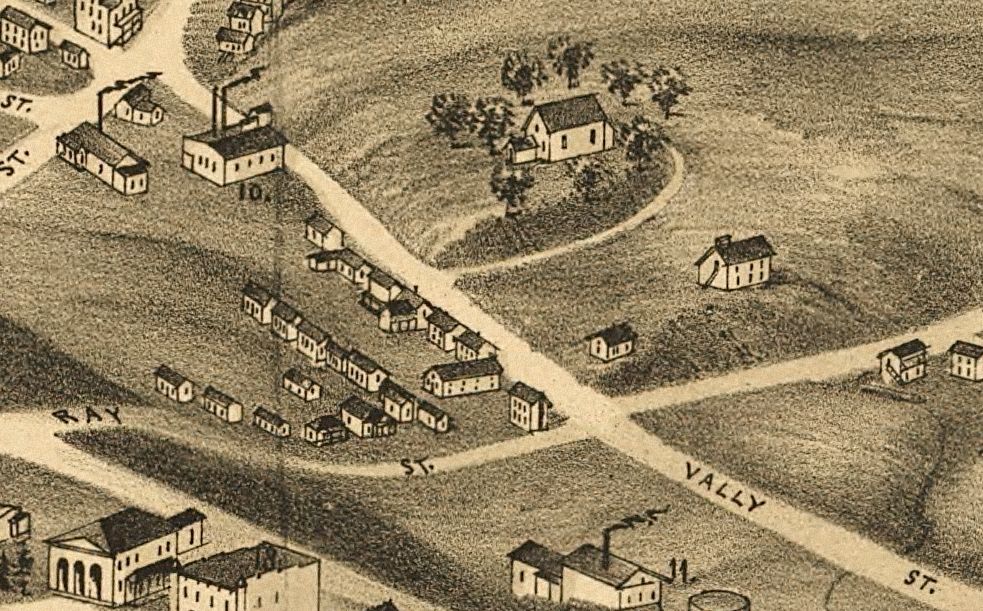

- On the town: Dicksontown circa 1891 detail of Library of Congress map

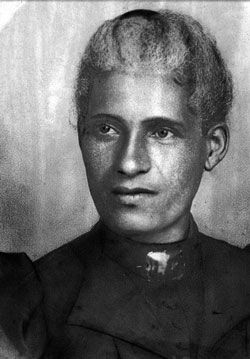

- Delia Dickson, Isaac’s wife. photo courtesy UNCA Special Collections

Just outside downtown Asheville sits Isaac Dickson Elementary, flanked by Interstate 240. Like many of the city’s elementary schools, it’s named after a local school administrator. Dickson, however, spent the first 24 years of his life as a slave.

Nonetheless, he went on to achieve considerable acclaim in his adopted community. Yet few today remember this remarkable man, and even fewer know his story.

Documentation of Dickson's life is fragmentary, and what little is known is mainly based on secondhand accounts. Despite being known as a community leader, he seems to have shunned the spotlight. Dickson didn’t have time for that: He worked hard for others, and they admired him for it.

Obscure beginnings

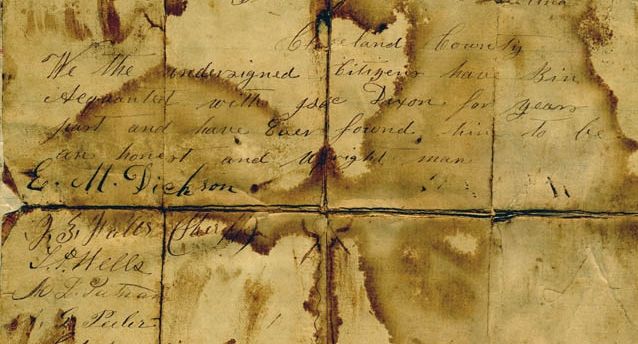

Dickson’s early life is mostly unknown. According to his family, his father was a slave owner and his mother was a slave. The only document directly linking Dickson to this period is the letter of recommendation he carried with him to Asheville in 1870. Seven people (not including the clerk) signed the Cleveland County court document (see sidebar, “Letter of the Law”). Who were they? And why did they want to help this young man?

The first signature holds the key. I spent years searching cemeteries, court records, maps, family trees and census data, until the survey from a legal battle led me to a stately old home, overgrown and barely standing. When I saw the signatures scrawled across the cracked plaster, I knew it was Elizabeth M. Peeler’s house.

A white woman born April 20, 1822, in Cleveland County, she married John Dickson, and in 1848 they had a son, Andrew (probably named after Elizabeth’s brother, Andrew Peeler, who’d died that year and was buried on a hill about a mile from her house).

A white woman born April 20, 1822, in Cleveland County, she married John Dickson, and in 1848 they had a son, Andrew (probably named after Elizabeth’s brother, Andrew Peeler, who’d died that year and was buried on a hill about a mile from her house).

Elizabeth took Andrew’s 8-year-old son Isaac into her household, but her nephew remained a slave because his mother, Rachel, was. After moving in with Elizabeth’s family the boy became Isaac Dickson.

Elizabeth's father-in-law, Gilbreth Dickson, was a gold miner, a large landowner, owned many slaves and was a director of the Wilmington, Charlotte & Rutherford Railroad. In 1860 his son John, Elizabeth's husband, was the line’s construction supervisor. As Isaac grew up, he probably worked for John and Gilbreth in various business ventures, gaining leadership skills that would serve him well later in life.

Elizabeth’s husband and only son both enlisted in the Confederate army; both were killed. She then endured a lengthy legal battle with Gilbreth to get her share of the land she was living on.

After the war, the Ku Klux Klan began to grow rapidly in the area. Plato Durham, a prominent lawyer who was Cleveland County’s delegate to North Carolina’s 1868 Constitutional Convention, was the state Klan’s grand chief; at the convention, he unsuccessfully opposed allowing blacks to vote. The local Klan used violence to intimidate Republicans and blacks.

Another Cleveland County native, Thomas Dixon Jr. (no relation), wrote nationally popular books and screenplays glorifying the Klan and inciting fear of blacks. D.W. Griffith’s 1915 film The Birth of a Nation (the highest-grossing movie of its day) was based on Dixon’s writings.

In 1867, perhaps fearing the growing violence, Elizabeth asked the county clerk to produce a document attesting to Isaac’s good character. Other white community members, including Elizabeth's brother Alfred (Isaac's uncle), also signed it.

This letter proved invaluable for Isaac, marking the beginning of his real emancipation. He kept it the rest of his life and passed it on to his daughter Mary Jane. Her daughter Jessie gave it and other family memorabilia to UNCA in 1977, the year before she died.

The hills where Isaac lived in Cleveland County afford a dramatic view of the mountains to the west. To Isaac, they may have represented freedom, opportunity and refuge. In 1868 he crossed them, golden ticket in hand, to make a new life.

Church family

Isaac moved to Morganton, where he met Cordelia Emealime Reed.  Her father, Silas Reed, was a carriage-maker there. After marrying around 1870, Isaac and Delia moved to Asheville — perhaps riding in a carriage made by Silas.

Her father, Silas Reed, was a carriage-maker there. After marrying around 1870, Isaac and Delia moved to Asheville — perhaps riding in a carriage made by Silas.

Soon after their arrival, their first child, Mary Jane, was born on Aug. 30, 1870.

In Asheville, Isaac met the Rev. Jarvis Buxton, the first Episcopal priest in Western North Carolina, who established Trinity Church. Buxton had founded Freedman’s Chapel in 1865 as part of Trinity’s mission to newly freed slaves, holding monthly services there until 1872. Later called Trinity Chapel, it eventually became St. Matthias’ Church.

The Patton family was instrumental in forming Asheville’s Episcopal community. Wealthy slaveholders, they owned much land around Asheville. Henrietta Kerr Patton had persuaded the church leadership to establish a presence in Asheville, prompting Buxton's move there. In 1859 she persuaded her husband, James Washington Patton, to donate the land on which Trinity Church stands. Henrietta's son Thomas Walton Patton donated the land for Trinity Chapel. Her daughter Fanny co-founded Mission Hospital.

The Patton family was instrumental in forming Asheville’s Episcopal community. Wealthy slaveholders, they owned much land around Asheville. Henrietta Kerr Patton had persuaded the church leadership to establish a presence in Asheville, prompting Buxton's move there. In 1859 she persuaded her husband, James Washington Patton, to donate the land on which Trinity Church stands. Henrietta's son Thomas Walton Patton donated the land for Trinity Chapel. Her daughter Fanny co-founded Mission Hospital.

Thomas Patton, a Confederate captain and slave owner, was loved by blacks and whites alike for his generosity to people in need. "The Law said he was my slave but often Law makes error,” Patton wrote about his former slave Sam Cope. “Indeed and in fact he was my devoted and loving friend and companion.”

Under Buxton’s direction, Asheville’s first school for black children was established in Trinity Chapel's basement in 1870. In 1872, the Rev. Samuel Vreeland Berry of New York City took over as pastor.

In 1874, five of Trinity Chapel’s nine-member congregation were Dicksons: Isaac, Delia and their children Mary Jane, John and Anna B. (named after Buxton’s wife, Anna). Two years later, the congregation had grown to 23 people.

Meanwhile, in 1872, the Rev. David Hillhouse Buel of New York came to Asheville to serve as principal of the Ravenscroft Training School for Ministry, "a school where postulants and candidates only for the holy ministry were received and instructed,” according to Buxton. He probably introduced Buel to Isaac, who later worked as his butler, perhaps until Buel’s death in 1893.

In the 1870s and 1880s, Isaac and his family lived at the school, whose driveway is today’s Ravenscroft Drive. In 1879 Isaac named his fourth child David Buel Dickson.

By 1885, Trinity Chapel boasted 200 congregants and a mission school with 85 students. Berry resigned that year due to ill health, however, and the congregation declined until the Rev. Henry Stephen McDuffey arrived in 1887. In 1888, Isaac named his seventh child Henry Stephen McDuffey Dickson. McDuffey re-energized the congregation, which grew until a larger building was needed.

Isaac undoubtedly attended the 1896 Easter service, the first one held in the newly renamed St. Matthias’ Church. A 26-voice choir and the 12-piece YMI Orchestra filled the new building with music that day. Isaac served as church treasurer for 35 years, served as sexton, helped transport construction materials and probably did much more that isn’t documented.

Growing family, growing community

Isaac worked hard for both his family (he eventually had 10 children) and his community.

In 1876, he paid $275 for two tracts near what is now Charlotte Street containing Thomas Patton’s former slave quarters. Isaac rented houses on the property to freedmen, and the area became known as Dicksontown.

By 1890, Isaac and Delia were living at 139 Valley St. He ran a general store, a coal yard and a taxi service next door.

On Aug. 31, 1890, Isaac hosted the first public meeting to organize the Young Men's Institute, which would promote social and economic opportunities for the African-American community. The meeting was called by Edward S. Stephens, a multilingual black world traveler born in Georgetown, British Guiana, and educated in Europe. The center was completed in 1892, funded by George Vanderbilt and the black community. Over the years, Isaac made many contributions to the YMI.

He also helped found Venus Lodge No. 62, the first Masonic lodge for Asheville’s blacks. Dickson facilitated the purchase of buildings on Market Street and served as treasurer for 25 years.

He also helped found Venus Lodge No. 62, the first Masonic lodge for Asheville’s blacks. Dickson facilitated the purchase of buildings on Market Street and served as treasurer for 25 years.

The 1916 Asheville City Directory lists Isaac as a janitor at Battery Park Bank, where he worked for 25 years. The 1918 edition has him as the janitor of Fredrick Rutledge & Co., an insurance firm. He probably worked until his death in 1919 at age 78.

In the 1960s, Dicksontown (including Dickson’s home) was leveled in the name of "urban renewal." Ironically, Asheville’s Public Works Building (which sparked its own controversy in the 1990s when it was dubbed “the Taj Ma-garage”) now occupies the home site.

Isaac Dickson was buried in Riverside Cemetery, where he now lies surrounded by his wife and children.

Isaac Dickson was buried in Riverside Cemetery, where he now lies surrounded by his wife and children.

An enduring legacy

One of Dickson’s greatest legacies was his role in creating Asheville’s public-school system, a contentious topic in 1887. Wealthy residents who sent their children to private schools didn’t want to pay taxes to support public education.

Former Republican congressman Richmond Pearson actively campaigned for public schools. He urged black residents to support the proposal, promising a black representative on the school board and no sharp rise in taxes.

The black community’s support proved crucial, as the proposal passed by a mere four votes (722-718) in July 1887. Pearson kept his promise, and City Council appointed Dickson, a respected community leader, to the school board.

A 1919 Asheville Citizen article about the city schools’ history, written six months after Dickson’s death, contains his only known quote:

“The young school had many discouragements, but it was blessed with a zealous school board — its members Messrs. W.W. West, W.F. Randolf, H.A. Gudger, S.R. Kepler, Dr. Millard and an honorable negro of the Old South. This man, Isaac Dickson, was scrupulously conscientious. During all his term of office he voted for but two [teachers applying] to white schools — Miss Susie Yeatman and Miss Mary Kimberly. When asked his reason for this he replied, ‘I knowed them two was quality.’ And old Isaac's discernment has been confirmed by hundreds who have been the beneficiaries of the fine quality of these good women.”

The school board met repeatedly (including Dec. 24 and 26) to select and renovate buildings. A vacant city-owned structure on Beaumont Street housed the first black school; a former military academy was leased for the white school. Both opened in January — the black school a week before the white one. But the Beaumont Street School could hold only 300 students, and on Jan. 9, 1888, so many children showed up that many went home crying.

In 1891, city voters approved a bond issue to build more schools, including a black high school on Catholic Hill, completed the following year. Edward Stephens, who organized the YMI, became the principal, and Mary Jane Dickson taught there through the early 1900s.

Isaac also made repeated gifts to A&M College in Greensboro (now North Carolina A&T State University). They were probably significant, since college President James Dudley (himself a freed slave) visited Dickson personally.

At a time when Jim Crow laws progressively undermined African-Americans’ newly won rights, Dickson not only prospered but invested in many organizations that made Asheville a more vibrant community. His spirit lives on in the institutions he helped build.

— Freelance historian Tom Burnet lives in Asheville; both his daughters attend Isaac Dickson Elementary.

This is my great grandfather! Thanks for writing out the story!

This is so exciting. This is also my great great grandfather. My grandfather was James Bryant Dickson. Which was Isaac’s son. I would love to meet you one day and bring my children so they can see this fascinating part of our family history. Thank you for your dedication and hard work.

Rebecca Withrow

P.S.

I wonder if my sister and I are related to the lady who said she thinks she may be related to Elizabeth Peeler.

I’m a descendant of him as well I was just visiting the area yesterday

may I speak with you. I Work at Isaac Dickson

Fantastic information! Thank you very much for writing this most detailed story of my great grandfather. My mother’s father was James Bryant Dickson, Issacs son. Her name was Emma Cordelia Dickson (Payden), named after her grandmothers on both sides of her family. James was one of the first black officers in the US Army Corps from North Carolina. He was a Luitenent.

Please call me if you’d like to know more information of the family. 330-285-8135

I really with the photos were captioned as to dates, locations, or other pertinent information?

What years are these photos from?

Where is he buried?

Amateur historians are awesome and this is a thorough article, but the editor at the Xpress should have done better to make sure it was complete to be truly proper and helpful.

Very helpful write-up. I used it as a reference several times in contributing to research to validate new photos found of Isaac Dickson with President Theodore Roosevelt in 1902. Thank you for the excellent research.

I’m including a link to this article for anyone who comes upon this researching Dickson, including his relatives in the above comments, as I think they would all find this interesting to the history of Dickson:

http://ashevilleblade.com/?p=1164

This my Great great grandfather I know very little about him love read this