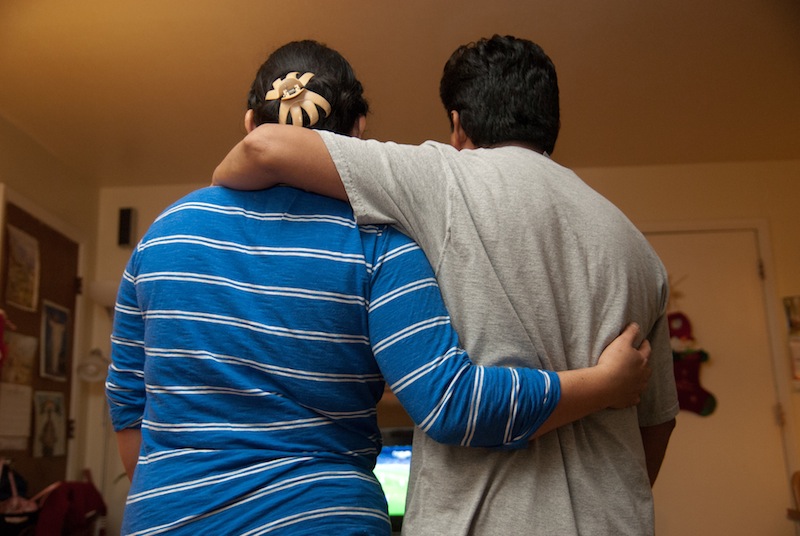

Together as one: The author chronicles the story of undocumented immigrants “Angela Tapia” and “Ernesto Galindo” (not their real names), pictured here in their Asheville living room. To respect the family’s privacy, Xpress chose to avoid photographing their faces. Photos by Max Cooper

Editor’s note: The following story resulted from a five-year relationship between the author, an associate professor of psychology at UNCA, and the family in question. All names have been changed.

In May 2005, Angela Tapia stood on the Mexican side of the Rio Grande River, waiting to cross to the United States with her husband, Ernesto Galindo, and their two children, Pedro, 10, and Maria, 6. About 12 feet wide due to dry weather, the Rio Grande looked more like a small lake than a river. But none of them knew how to swim, and the “coyote” they’d hired to take them across was telling them to wade in, promising to return the backpack containing their possessions on the other side. (Coyote is slang for people smuggler.)

Angela hadn't given much thought to the perils of crossing the border. She and Ernesto had decided to emigrate mere weeks before, and she’d wrongly assumed it would be easy.

This Asheville family is part of a heated national immigration debate. Here is their story.

A home of one’s own

Ironically, the impetus to emigrate was the family's desire to build a home on land they’d purchased in their own country (a common motivation for immigrants worldwide). Mexican salaries are much lower than here, unemployment is higher and loans harder to get. Houses paid for with U.S. savings are likely to be larger and nicer, with wood or tile floors instead of dirt.

Angela's sister, Bertha, who’d come to Asheville with her husband and two children in 2000, had said Angela and Ernesto could earn a lot more money here to finance their home. Now was the time, because Bertha’s brother-in-law, who’d briefly returned to Mexico, could help them cross the border, and she’d lend them money to cover expenses.

Despite having relatives in the U.S., Angela and Ernesto had never seriously considered coming here. But in Mexico City they lived with his parents, sharing cramped quarters with up to 13 people. To bathe, they used a big bucket filled with cold water from a hose, to which Angela would add boiling water. Family members would stand by a drain and dump water on themselves from a plastic container.

Ernesto and Angela shared their double bed with the children. Life was hard, money was always tight — at times they could barely afford staples like tortillas and beans — and escaping the inevitable family conflicts seemed a remote dream.

Ernesto often helped his mother prepare food for her taco stand before taking the bus or riding his bike to the textile plant where he worked every day but Sunday. He made about $100 a week stitching emblems into baseball caps and T-shirts.

He’d earned a bit more delivering pharmaceuticals. But in 1999, a gunman put a pistol to his head, threatening to blow his brains out if he didn't turn over the 2,500 pesos (about $250) collected that day.

“God, take care of my children,” Ernesto prayed, but after his partner surrendered his weapon and Ernesto handed over the money, the robbers fled. Ernesto left his job soon after; he later learned that a guard he’d worked with had been killed in a robbery.

But the family’s struggles continued, and after discussions with Angela, one day in April 2005 Ernesto said, “Let's go.”

Crouching and bending

U.S. immigration policy has varied widely over the years. Before 1900, few Mexicans came here, though it wasn’t illegal.

But in the early 1900s, U.S. companies began recruiting Mexican workers to offset labor shortages in fields, mines and railroads. Stereotypes were common: Farm labor, noted George P. Clement of the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce, involved tasks "to which the Oriental and Mexican, due to their crouching and bending habits, are fully adapted, while the white is physically unable to adapt himself to them."

During World War I, the U.S. government encouraged Mexican immigration, and the postwar boom boosted the demand for workers. Between 1900 and 1929, the number of Mexican-born people in the United States grew from about 100,000 to 740,000.

Juarez and beyond

The family got up at 5 a.m. on a Saturday, and Angela packed an orange backpack as her sister had advised: a change of underwear for everyone and copies of the children's birth certificates.

After tearful goodbyes, they met the brother-in-law, Antonio, who’d arranged for a coyote to take them across. Antonio had a bad knee and didn't want to ride a bus for 1,200 miles, so the family took a plane (for the first time) to Juarez, just across the Rio Grande from El Paso.

With difficulty, they found the coyotes, who had them take a bus and followed in a car. Passing battered homes and stony faces in a city notorious for rape, murder and hundreds of drug-related shootings, Angela prayed, “God, let us arrive all right.”

Eventually they came to an isolated area; the coyotes collected $50, telling them to cross the river and then run till they reached a highway. The water reached the men's shoulders; Antonio carried Pedro and Ernesto held Maria.

On the American side they took off running. But instead of the street where the coyotes were to meet them, they found only the Border Patrol. "Don't move," the agents said, taking them into custody.

Quotas and deportations

The U.S. Border Patrol was created in 1924; that same year, Congress established quotas restricting southern and eastern European immigrants, who were deemed inferior. "The United States is our land," declared Washington state’s Rep. Albert Johnson, a principal author of the act. "The day of indiscriminate acceptance of all races has definitely ended."

Yet there were still no quotas for Mexicans, thanks to Southern and Western legislators whose constituents needed cheap labor. Some Mexicans did cross illegally, but if caught, they were simply sent to a border station to pay the $8 fee.

The Great Depression, however, ushered in an era of Mexican deportations; over the next decade, thousands of immigrants were sent home, leaving some 377,000 on U.S. soil by 1940.

Stalled

After being interviewed, fingerprinted and photographed, the family was transported back to Juarez and given bus tickets home. But a man they’d met in detention said he and his girlfriend were coyotes who could house them for a day and then take them across.

Skeptical but lacking options, the family accepted. Two days later they were just about to cross again when the coyote shouted, "They're coming!” A Mexican police patrol approached, and the family dashed across.

After hiding for a few minutes, they walked past a ranch, hid again, crossed fields and orchards, and eventually ran into a friend of the coyote's. Having Ernesto and Antonio lie on the floor, he drove them an hour north to Las Cruces, N.M., where the coyote's in-laws lived. They proved reluctant hosts, however, fearing neighbors would get suspicious.

The journey stalled while Angela's sister wired the coyote $2,000. They spent a week in a cockroach-infested apartment nearby, wondering what to do next. Finally, Antonio heard about a young man who could take them to Santa Fe or Albuquerque in the back of a tractor-trailer, a roughly three-hour journey, for $7,000.

With tightened border security, unauthorized immigrants have been taking bigger risks. As Angela weighed the decision, she remembered an incident two years earlier when 19 of the 100 immigrants packed in an airtight tractor-trailer had died of intense heat, including a 5-year-old boy found in his father's arms.

Scared but determined, Ernesto and Angela pressed on. Nearly missing the departure because their ride was late, they joined about 70 people in the dark space; their children snuggled up and went to sleep. After six hours on the road and a night in a hotel, they boarded a Greyhound to Denver. Continuing through St. Louis, Memphis and Knoxville, they finally arrived at the Tunnel Road bus station on May 20, 13 days after leaving Mexico City.

The journey plus other expenses (such as a compact car with almost 300,000 miles on it) had cost $14,000. They were starting their new life with a bigger debt than they’d ever imagined.

Bye-bye Braceros

After focusing on deportations in the 1930s, U.S. policy shifted once more during World War II, as the Bracero program brought in temporary Mexican workers. By the early 1960s, some 450,000 guest workers were entering the U.S. each year, plus about 50,000 people granted permanent visas.

But in 1964 Congress, concerned that the Bracero program exploited workers, ended it over Mexico’s objections. A 1965 law capped visas for Mexicans at 20,000 per year. Nonetheless, Mexican immigration continued at the well-established pace of about 500,000 per year — only now the vast majority were unauthorized.

A 1986 law heralded as the solution to illegal immigration granted amnesty to some 2.7 million people while establishing sanctions for employers hiring unauthorized immigrants.

Meanwhile, the number of Border Patrol agents jumped from about 1,500 in the 1960s to 10,000 in 2003 and more than 20,000 by 2009. Regular trips home once kept the number of immigrants in balance, but with tighter security, many now opt to stay here. Meanwhile, most people who attempt to cross are ultimately successful. Between 1980 and 2008, the number of unauthorized Latino immigrants in the U.S. snowballed from about 1 million to 7 million.

Settling in

The day the family arrived in Asheville, Ernesto's brother-in-law took him to the restaurant where he worked. The owner hired Ernesto to wash dishes for $80 a week (less than the minimum wage). After stints at other restaurants he now works at a hotel, making about $8 an hour.

Angela got a job busing tables for $7.80 an hour. One day a customer gave her a dollar, which she pocketed; a waitress told the manager Angela had stolen her tip. Angela tried to explain that she’d thought the tip was for her, but her English was limited and she couldn't find the words. After getting fired, she went to a different restaurant, earning $6.25 an hour doing food prep and flipping hamburgers. She now works in yet another eatery.

The family paid its debt in a year-and-a-half and then began wiring payments to Ernesto's father to start building their home; they also occasionally sent money to their families. Both Angela and Ernesto pay federal and state taxes; they file a joint return annually.

At first, Pedro thought every police officer he saw was going to grab him. Shaking off his disappointment at having to repeat the fourth grade, which he’d just completed in Mexico, Pedro soon took off academically, learning English quickly.

"He worked so desperately to interact," his fourth-grade teacher recalls. The Mexican schools seemed to have prepared Pedro well, and his parents were “just so respectful."

Still trying to master English, Pedro didn’t do well on the end-of-grade tests, but he was promoted and had a successful fifth-grade year, becoming a popular classmate.

Maria, too, had to repeat the grade she’d already completed. She struggled at first, enduring painful headaches that left her in tears. But her first-grade teacher saw the same strong drive in Maria, who did so well that she skipped second grade.

Maria placed out of English as a second language after two years, and Pedro after five. They often speak English to each other, even at home. In middle school, Pedro regularly made the honor roll; so does Maria. She plans to do community service next year, and she’s thinking about a career in criminal justice. Neither reports encountering much prejudice from classmates.

Continuing challenges

Still, there are struggles. Athough Pedro completed a high-school driver's-education course, he still doesn’t have a license. If anyone asks why, he’ll just say he’s too lazy or hasn't had time. That kind of secrecy is common among unauthorized high-school students, even with their friends, according to Roberto Gonzales of the University of Chicago.

North Carolina used to issue driver's licenses to any adult who passed the exam, to maximize the number of safe, trained, insured drivers on the road. But after 9/11, the state restricted licenses to citizens and authorized residents. On Feb. 14, however, the state Division of Motor Vehicles announced that it will issue licenses to unauthorized immigrants with federal work papers starting March 25.

Meanwhile, Pedro now makes mostly A’s and B’s; he’s played soccer and serves in the JROTC color guard. A portrait of him in uniform, his face gravely serious, hangs in the family’s living room.

Pedro dreams of working in international business, where his Spanish would be an asset; he wants to attend college but isn't sure he can.

Shifting sands

A 1982 Supreme Court ruling requires public schools to accept unauthorized immigrants. Writing for the majority, Justice William Brennan said these people were encouraged to work for cheap wages yet denied the education that could prevent their ending up on welfare or in prison.

But at the college level, unauthorized youth face significant obstacles. Ineligible for federal financial aid, they must pay out-of-state tuition at most public universities. At UNCA, in-state tuition is about $6,000 a year, and out-of-state tuition nearly $20,000 — a $56,000 difference over four years.

About a dozen states have so-called DREAM acts that create a pathway to citizenship and allow unauthorized youth to pay in-state rates. A 2005 North Carolina proposal died after opponents launched a campaign arguing that unauthorized immigrants would take college slots away from U.S. citizens.

Last June, the Obama administration established the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program by executive order, halting most deportations of unauthorized immigrants who came here as children and allowing them to attend college and work. But individual states still decide whether they’ll be eligible for in-state tuition or driver's licenses. Participants must reapply every two years — and while Obama’s re-election protects the program for now, a future president could end it.

Mixed feelings

As Pedro and Maria wait to see what the future holds, their parents (who’ve worked more than seven years with less than a week's vacation) are still trying to complete their house in Mexico. A concrete-block shell with holes awaiting windows and doors, it has a living room, kitchen and bathroom on the first floor and three bedrooms upstairs.

Having grown accustomed to American life, however, the family has mixed feelings about leaving Asheville. Pedro used to think he’d return to Mexico, get his papers in order and then come back. But he recently applied for the DACA program, which would allow him to attend college and work here for at least the next two years.

"It would provide calmness," he notes, "and not so much worrying about what could happen."

Former Asheville resident Joseph Berryhill is on a leave of absence from UNCA.

Great piece. It’s important to note that what was once north Mexico is now part of the Southwest US, sold by Mexico to the US after the Mexican-American war in 1847.

So there are Chicano Mexicans who are indigenous to what is now the United States, and have more of ancestral claim to this land than any white folks.

Just because whites have occupied this land for hundreds of years doesn’t mean no one else has claims to it.

It makes me sick to think of all the heartache these border issues have caused, as well as the US economic policies like NAFTA which have made Mexican emigration such a necessity.