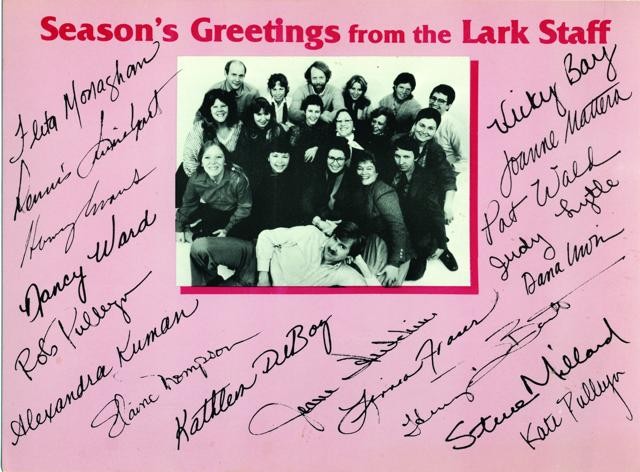

- HOLIDAYS PAST: Founded as an independent publishing house in 1979, Lark Books employed a host of creative professionals, averaging nearly 70 craft-oriented books a year. photo courtesy of Rob Pulleyn

- CREATIVE COMMUNITY: Rob Pulleyn, who co-founded Lark Books, says it built a creative network over the years. Its closure is “a personal loss and cultural loss,” he says. photo by Megan Kirby

On Feb 19 Lark Books employees got the word: The longtime publishing house is closing, and staff must move out by the first week of May.

That’s when Lark — founded as an independent publishing house in 1979 by Rob Pulleyn with his then-wife, Kate Matthews — will officially relocate to the New York offices of its parent company, Sterling Publishing, a subsidiary of Barnes & Noble.

The news came during an early-morning staff meeting, mere hours before making local headlines. That meeting was followed by an email that Caitlin Friedman, Sterling’s director of marketing and publicity, sent to Lark’s network of local, regional and national authors, agents and freelancers.

Friedman announced Sterling’s plans to transfer all editorial, creative and marketing positions to its Manhattan headquarters by May 2. “We are energized and excited about the future of the Lark imprint in New York,” Friedman said in the email. “We also recognize the hard work, vision, passion and dedication of the Asheville team and want to take this opportunity to thank them all for their many years of service.”

Efforts to reach Lark employees for comment were met with requests to forward any and all questions to Barnes & Noble’s senior vice president of corporate communications and public affairs, Mary Ellen Keating. “Our company policy,” Keating told Xpress, “is for the spokesperson to respond and not our employees.”

Keating offered a brief explanation and timeline: “Sterling Publishing is consolidating the operations of its Lark Books craft imprint into the New York office, effective Feb. 19. … The transition is expected to take 60 days.”

Lark’s 18 office positions will transfer to New York, but the employees will not. “As part of the consolidation, Sterling will close Lark's office in Asheville,” Keating said. “Lark titles will be reassigned to the New York-based editorial, creative and marketing staff.”

No one from the Asheville office will be moving to New York, according to Keating.

For 35 years, the local publishing house has specialized in craft and design books. It leaves behind an empty footprint on the third floor of 67 Broadway, where the company has been the late 1990s. The building's ground floor now houses the Center for Craft, Creativity and Design, which purchased it in August from Pulleyn. Lark moved its offices upstairs.

“We had a lease with a clause that allowed them to withdraw with 90 days’ notice without penalty,” says Stephanie Moore, CCCD’s executive director. The agreement was inherited in the sale of the building and echoes Pulleyn’s laid-back operational approach. The craft-based nonprofit currently has no plans or tenants lined up for the space.

“I understand what’s happening in the publishing industry,” Moore laments, “but now a major employer in our creative industry is just gone.”

Brochures to bindings

At its height, Lark Books had roughly 50 employees and produced, on average, 65 books a year. Its origins, though, were much humbler. Lark began as a monthly, one-page newsletter that Pulleyn wrote and distributed for customers at the Santa Fe, N.M., crafts-supply shop that he and Matthews owned and operated.

“We had a retail store, and so I started a newsletter for our customers,” Pulleyn says. He admits he was always better at creative and editorial endeavors rather than customer service, so he saw the letter as an escape. “The newsletter,” Pulleyn says, “was both a way to connect with customers and get away from them at the same time.”

The newsletter continued to grow, eventually turning into a bimonthly publication called Fiber Arts Magazine. The duo took the magazine, uprooted and moved to Asheville in 1979, setting up shop at 50 College St., now home to a restaurant — Table and the Imperial Life. Shortly after the move, Pulleyn and Matthews, with the help of Swedish investors, started Lark Books.

Though similar, the name “Lark” bears no relation to the Larkin Books of Thomas Wolfe’s Look Homeward Angel, says Pulleyn (coincidentally though, the business’s initial limited liability company was called Altamont Publishing.) Lark is an acronym of the founders’ and investors’ first names: Lucas, Albert, Rob and Kate.

The first books rolled off the press in the early 1980s as the company narrowed its focus to producing craft-oriented how-to, DIY and design books.

The company had a few big hits in the late ’80s, Pulleyn says, before adding a mail-order catalog. “All it takes is a few books to keep a publisher alive,” he said. “We ended up with about 50 employees and publishing 60 to 70 books a year.” Lark sustained those levels through 1999, when Pulleyn sold the company to Sterling.

By that time, Pulleyn’s love of creative work and his inherent distaste for business processes had resurfaced. “It was time to sell,” he says. “I was better at the editorial and creative work, not the day-to-day business work. And the idea of someone else taking over — that was wonderful.”

Sterling, which Lark had used as its large-scale distributor — a practice common to small publishing houses — acquired the company directly from Pulleyn. Sterling dropped the mail-order catalog system almost immediately and implemented corporate-style titles and positions. While the changes were minor, they were still a significant departure from the past. Pulleyn, for instance, was named Lark's CEO, with a five-year contract. It was the first time anyone had a title, he says. All the same, at the time, he felt that he had sold Lark to a company that would safeguard its ideologies.

But in 2003, as Pulleyn’s tenure as CEO drew to a close, Sterling agreed to a buyout by nationwide bookseller Barnes & Noble.

“It was a shock to bookstores when Barnes & Noble began buying publishers,” Pulleyn says, citing the B&N’s goals of lowering its bottom line by owning that bottom line — the publishers. Such buyouts mean slimmer operating budgets and staff reductions.

Thus began the slow trickle from Asheville to New York, one position at a time, says Pulleyn.

“The management of Lark Books since the takeover of Barnes & Noble has been unfortunate,” says Pulleyn. “Many of the people making decisions were the bean counters. All that is important to the business, but those decisions were to the detriment of the company. They let people go that were really good.”

Love and loss

In losing Lark Books, Asheville loses more than just 18 jobs, says Pulleyn. It weakens an entire creative network.

Since the books were being made here, Lark made a point to outsource its graphic and conceptual production to local authors and artists alike. If a photographer, author or someone to sew, stick, felt or throw a pot was needed, they were within phone call and a short drive.

“It was one of the best gigs in town,” says Steve Mann, a local photographer and Lark freelancer since 2002.

“They were great people to work for,” he says. “Most of the staff were artists in their own right.” They were photographers and ceramicists, fiber artists, woodworkers and writers, he explains. Some had side projects and artist studios. Others freelanced for local creative organizations and businesses, including Xpress. “These people live and breathe it, day in and day out,” he says. “I think that’s what’s going to be hard to replace.”

But even as the company faced mounting budget and staff cuts in recent years, it continued to support its local network. “Lark was one of the few shows in town where you could have steady work,” says Lynn Harty, a freelance photographer for the company since 2008. “As they got whittled down, they made a point to spread the work around and keep using us local photographers.”

Pulleyn fears that moving the company to New York will ultimately weaken the focus on craft, or even kill off the imprint. “Where’s the internal logic?” he asks. “You publish fiction where fiction is dominant. You do craft books where craft is made. Craft doesn’t come from New York.

“It’s a personal loss and a cultural loss,” says Pulleyn. He compares Lark’s closing to losing a loved one. “It’s the network of creative people that help to define this community and the fact that there was this publishing company here that needed help directly from that community.

“Lark helped to create that community. It helped to define it and to help the creative people make a little bit of their income,” says Pulleyn. “That’s what Asheville loses.”

Lot of story missing here! Puff piece.