Less than three years after North Carolina passed the groundbreaking Clean Smokestacks Act, the state now appears to be moving in the opposite direction when it comes to regulating air pollution from old, grandfathered power plants. But a grassroots environmental group based in Sylva is determined to hold North Carolina’s feet to the fire.

State Attorney General Roy Cooper grabbed headlines last month when the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency agreed to rule on his petition to force coal-fired power plants in neighboring states to reduce the amount of pollution they contribute to North Carolina’s dirty air. Cooper claims that pollutants carried here from Georgia, Maryland, South Carolina, Tennessee and Virginia are the reason our state isn’t meeting federal air-pollution standards.

“North Carolina is working hard to clean up our own air, but those efforts alone won’t stop the dirty air we inherit from other states,” Cooper stated in a Feb. 17 press release.

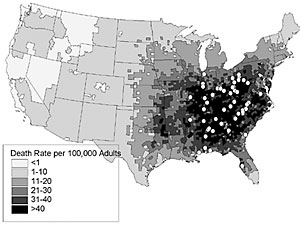

from Clean Air Task Force, “Power to Kill”

Lethal loophole? The 51 grandfathered power plants the EPA sued for avoiding new pollution controls when they expanded (white dots) are in the areas of highest risk for premature death due to particulate emissions from power plants. www.cleartheair.org

|

But just a week before (and with far less fanfare), the state Division of Air Quality had taken steps to enable North Carolina’s own dirtiest plants to avoid installing costly new pollution-control devices required by the Clean Air Act. Pollution from these plants (including some east of here that have helped push the state’s biggest metropolitan areas into nonattainment status for ozone) also wafts into the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, contributing to Western North Carolina’s deteriorating air quality.

Canary Coalition Director Avram Friedman, for one, believes the state ought to practice what it preaches. “By setting the bar low here at home, it’s really weakening us in our moral ability to go outside the state and try to convince other states to raise their standards,” he argues. But the watchdog group has a plan for derailing the state’s proposed rule change (see “Full Steam Ahead” on page 15).

On Feb. 10, the state Environmental Management Commission approved the Division of Air Quality’s recommendation that North Carolina revise its New Source Review (NSR) regulations to conform more closely to the new, lower standards for grandfathered smokestacks that the EPA is attempting to institute. That will clear the way for rapid implementation of the watered-down state rules — unless the coalition’s strategy to force the measure to an out-in-the-open vote in the General Assembly succeeds.

New Source Review, created by Congress in 1977 as part of the Clean Air Act, was designed to compel older industrial facilities that were originally exempted from the clean-air requirements to beef up their pollution controls when they renovated, modernized or expanded. Many utility companies in the East and Southeast, however, have dodged the costly upgrades by regularly claiming that renovations and expansions of their coal-fired power plants were only “routine maintenance.”

Under the Clinton administration, the EPA began cracking down on such abuses. It sued 51 grandfathered power plants in the East and Southeast — including eight North Carolina plants owned by Duke Energy — for violating NSR. Then, under the Bush administration, the EPA was forced to do an about-face, as reported in The New York Times in 2003. The agency relaxed the NSR standards for both Prevention of Significant Deterioration (PSD) and Routine Maintenance, Repair and Replacement (RMRR) in 2002 and 2003. Although many of the utilities settled with the EPA, others held out, counting on the changed rules to weaken the government’s legal case against them.

On Feb. 3, Duke Power and the EPA crossed swords in a Richmond, Va., federal appeals court in what will likely be the decisive duel of this battle. A spokesman for the five other utilities still being sued told The Charlotte Observer they are closely watching Duke’s case, which should be concluded this summer.

The PSD change means aging smokestack industries are no longer required to upgrade controls on all of their facilities when they renovate or expand — only on enough of them to satisfy an overall pollution cap the government sets for each plant, which the EPA and industries contend would not increase air pollution. The more controversial RMRR change would allow utilities and other industries to undertake renovations or expansions worth up to 20 percent of the plant’s value without triggering the upgrade requirement.

According to the EPA’s justification (as published in the Federal Register), the changes are “intended to provide greater regulatory certainty.” But 14 states, the District of Columbia and 20 cities have filed suit against the agency, maintaining that the changes unconstitutionally reverse the intent of Congress and will irreparably harm their residents. (North Carolina did not join the suit.) Both sets of changes are now tied up in the courts, and a federal appellate judge has temporarily blocked the RMRR change.

Full steam ahead

Even if the proposed EPA standards survive the court challenges, states are not required to adopt them. Federal pollution regulations provide a base line: States cannot adopt weaker rules, but they can choose to enforce more stringent ones.

Nonetheless — and even though an adverse court ruling could undo the changes at any time — North Carolina went ahead and held public hearings in Charlotte and Raleigh last August on how the state should respond to the NSR changes. The agency presented three options: Keep the stricter state rules unchanged; adopt the new federal changes; or adopt a toned-down, compromise version. (All three options addressed only the PSD changes.)

Business representatives argued vociferously in favor of the federal changes; environmentalists insisted just as loudly that the state rules should be kept as is.

Duke Power, Progress Energy and the Charlotte Manufacturing Business Alliance all echoed the EPA’s justification for streamlining the permitting process.

“It is crucial that North Carolina rules are consistent with those of surrounding states in order to ensure a level playing field,” wrote Alliance representative Bob Kellen in an open letter to Charlotte Chamber of Commerce members. If the state were to keep stricter standards than its neighbors, he argued, it “will muddy the permitting process and interfere with business decisions to expand or relocate.”

But Friedman and other environmentalists told the Division of Air Quality that the federal rules are simply a way to enable industries to avoid installing pollution-control devices.

“The purpose of the NSR provision in 1977 was that these older plants would eventually lose their exemptions — they’d be phased out,” Friedman told Xpress. “And they haven’t done that. And now they’re just finding another way of delaying that process. You know, after all this time, they should use modern [anti-pollution] equipment.”

After the hearings, the Division of Air Quality proceeded with its compromise proposal, which makes only minor alterations in the new federal rules (such as explicitly requiring plants to keep records of their emissions — which the federal rules do not).

Ordinarily, the new state rules would take effect once they’d been approved by the General Assembly’s Rules Review Commission. But the Canary Coalition plans to take advantage of an obscure provision in state law to block the rules. This relatively new legislative procedure “was originally designed by industrial interests to block strong environmental regulations from being implemented,” according to a Coalition press release.

“Any 10 citizens can send in letters of objection and ask for legislative review, to interrupt the process,” Friedman told Xpress. “This is what we’re going to do.”

If successful, the move will delay the rules’ implementation till the start of the 2006 legislative session, at which point any legislator can introduce a “disapproval bill.” If such a bill passed, it would kill the new rules.

The letters of objection must be written in specialized legislative parlance. Accordingly, the coalition is urging citizens to copy a sample letter of objection from its Web site (www.canarycoalition.org) and send it to the Rules Review Commission before the March 18 deadline.

“The state made a decision when it passed the Clean Smokestacks Act to work for cleaner air, and we shouldn’t be going backwards at this point in time on any air-quality standards,” Friedman proclaims. “It’s working against what we’re trying to do with the Clean Smokestacks Act.”

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.