|

It was Feb. 16, 2004, a chilly midafternoon. Kay Carpenter, a 40-something blonde with six cats and a doctorate in psychology, was seated in her kitchen. The phone rang. Carpenter answered.

“I’ve got a job for you,” a male voice intoned. “A murder. Yes or no?”

“I need to think about it,” she replied.

“Thirty minutes. Then I call someone else.”

Twenty-nine minutes later, Carpenter agreed to ghostwrite the story of a 16-year-old murder. It was a decision that would change her life, plunging her into a weird world of feuding cops, Montana gangs, missing girls and a hijacked car allegedly spotted in dozens of states and Canada — while it actually lay buried in the murderer’s front yard for 14 years.

Born in Austin, Texas, Carpenter taught psychology at Houston Baptist University and the University of Houston, reported for the Houston Community Newspapers and worked as a freelance writer. Between jobs she tried her hand at fiction, completing three novels, which she shelved before moving to Western North Carolina with her husband in 2001. In Asheville, she taught a course sponsored by the city’s Parks and Recreation Department called “How to Write the Story of Your Life.” Inspired, she decided to take her own advice.

Drawing on her early years in Austin, Carpenter completed and published her first novel, Queen of Mean Street (Infinity Publishing, 2002). The same publisher issued her second semiautobiographical novel, Bye-Bye Mean Street, two years later. Today, Carpenter dismisses these books as “chick lit”; nonetheless, they were forays into a world of sleazy deadbeats, murderers and misogyny that would become all too real in the author’s next literary incarnation.

Still, Carpenter kept at it, freelancing and ghostwriting for a dozen years or more. Accordingly, her work was familiar to an editor at The Floating Gallery, a multimedia design-and-production company in New York City that was contacted by Sheila Kimmell in 2003.

Kimmell’s 18-year-old daughter, Lisa Marie, had been kidnapped, raped, tortured and murdered in 1988. The family had endured years of pain over their loss while law-enforcement investigations slowly petered out, leaving the Kimmels with no closure. Then, in 2002, a DNA sample from a man imprisoned for a firearms violation and later charged with the death of a cellmate matched samples taken from Lisa’s corpse. Sheila Kimmell was ready to tell her family’s story just as the trial of Dale Wayne Eaton was about to begin. Long on story but short on writing skills, the bereft mother went looking for help.

Thus began a collaboration across 1,400 miles. “The first few months were learning curves for both of us,” Carpenter recalls. “I had written about crime in my novels, but it wasn’t based on hard-core investigative research.”

Soon, Kimmell shipped her ghostwriter a box containing journals and “about 400 pages of past newspaper articles and legal documents. She sent me videos, cassette tapes and anything else I needed.” Carpenter waded into the pile of data and anecdotes and began considering how best to distill the mass of material into a readable story.

The case had led investigators through a tangle of conflicting reports and accusations. On March 28, 1989, a note was found taped to Lisa’s headstone. Signed “Stringfellow Hawke,” it read, in part, “The pain never leaves it’s so hard without you you’ll always be alive in me.” (Much, much later, the writer of those words proved to be the killer.) Rival drug gangs, meanwhile, used the girl’s murder to implicate their enemies, each offering “clues” that implicated the other (all of them turned out to be false). And the sheriff on the case harbored bitter resentment toward outside law-enforcement officers involved and actively worked against them. He then attempted suicide on the second anniversary of Lisa’s demise, making some wonder about his own role in her abduction. (He succeeded in killing himself 10 years later.) Lisa’s story was aired on Unsolved Mysteries, and tips from people claiming to have spotted her car, with its distinctive “Lil Miss” plates, poured in from across the country.

Meanwhile, Eaton’s trial was playing out, and despite a deep-seated fear of flying, Carpenter decided to go to Wyoming for the final days. “I spent almost every possible moment interviewing somebody,” she relates: detectives, the county coroner, a special agent for the Burueau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, lawyers and the district attorney. And Carpenter was in the courtroom when Eaton was found guilty of first-degree murder.

But after the excitment came months of writing and rewriting drafts, incorporating corrections and additions from Kimmell. And Carpenter soon realized that she and Kimmell had somewhat different goals. Kimmell wanted to tell her daughter’s story and explain her family’s reaction to the tragedy, along with what they’d learned through the years. But Carpenter wanted to go further, writing about the perpetrator, too, and giving a voice to other possible victims of Lisa’s killer. Eventually the co-authors agreed on the broader approach.

Like the protagonist of her first novel, Carpenter herself had an abusive boyfriend in high school and had to obtain a restraining order to keep him away. And like her fictional character, Carpenter’s ex was later put on trial for murder. “He was found not guilty, but I think he was capable of the crime,” she explains. “I have a desire to expose the thinking of these manipulating, possessive, abusive men. That’s what I hoped to do by writing about Dale Eaton.” (It may also help explain why most of the male characters in Carpenter’s two novels, even the putative “good guys,” came across as pretty repulsive, at least to this reader.)

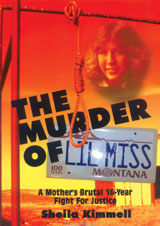

Clearly, however, Carpenter really hit her stride when she decided to combine her reportorial experience and her apparent fascination with murder. The finished book, The Murder of Lil Miss (Eagle Crest Publications, 2005), is as compelling as a fictional whodunit and as well laid out as a front-page news story. Using a first-person narrative in Sheila Kimmell’s voice, the authors tell the tale of a heinous abduction/rape/murder. They also offer portraits of both victim and killer as well as tantalizing clues suggesting Eaton’s possible connection to a series of other unsolved murders in the region.

In the course of carrying out her writing chores, Carpenter also found herself becoming part sleuth. “It’s like being able to play Sherlock Holmes without dealing with the bad guys,” she notes. “And I’ve gotten to know so many people through this — you bond with people in an unusual way.”

Carpenter says she formed particularly close friendships with Don “Flick” Flickerson, the ATF agent on the case, and James “Doc” Thorpen, the tuba-playing Natrona County, Wyo., coroner. And her camaraderie and honest dealing with the principal detectives, Lynn Cohee and Dan Tholsen, led them to share “piles of their original reports. When they trust you, they really trust you,” says Carpenter. “One investigator sent me over 300 pages of documents. That’s when you hit gold. You can go through public records forever and find nothing, but in the detective’s notes some amazing stuff comes out!”

But Carpenter has also learned what not to bother with. “Not every murder case or serial killer is going to make a good book,” she notes. “For instance, some editors want a high body count, but there needs to be an element of community interest. In the Elizabeth Smart case, thousands of people went out looking for one missing person. With the Green River Killer, there was a high body count [48 women], but nobody cared about them.”

And cases entailing multiple story lines are inherently more interesting than more straightforward ones, Carpenter maintains. The Kimmell case, for instance, was full of twists and turns right up to the end. Even after the DNA match and the discovery of the missing vehicle, the prosecuting attorney was charged with felony fraud just before the trial began but refused to drop out of the case until pressed hard by other law-enforcement officials.

The whole experience proved interesting enough, in fact, that Carpenter is already working on another case, this time in her own name. She has a proposal in to St. Martin’s Press concerning one Charles Sinclair, “a serial killer who didn’t fit the typical pattern, since he targeted so many different victims in different ways. He principally preyed on coin dealers, but he engaged in rape and kidnapping too,” she notes. In the meantime, Carpenter says she has tantalizing leads on the story of the Texas yogurt-shop murders, involving four young girls and arson to boot.

“I’m a true-crime writer now,” says Carpenter. “I hope to publish one per year; I really hope to do a lot more.”

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.