Anyone who’s survived adolescence knows how rough it can be. The hormones, the willfulness, the rebellion, the confusion, the acne—and that’s under the best of circumstances. Imagine facing the tumult of that age in poverty, with one overworked, underpaid parent, and maybe with a family or community history of abuse or the scourge of drugs.

In his role as a social worker at Randolph Learning Center in Asheville, Eric Howard sees some hard cases—sixth- through ninth-grade students who have failed academically at other schools in the Asheville system or have been removed due to their behavior or learning difficulties.

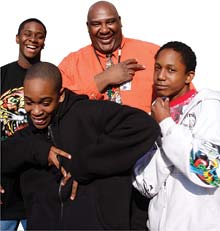

Known to students as “Big E” for his imposing build, Howard played offensive tackle in college football. But his heart, it seems, is equally sizable. Howard strives to bridge the gaps dividing parents, students and the school, checking in and finding them help when it’s needed. Xpress caught up with Howard after school recently to learn about his job, the students he works with and the challenges they face every day.

Mountain Xpress: What does a school social worker do?

Eric Howard: I’m an advocate for the kids and their families, a liaison between the families and the school. It’s my job to bring people together.

What’s the student body like here at Randolph?

We’re about 98 percent African-American here; we have some Caucasian kids and some Latino kids. But all of our kids are what are called “high-end kids,” whether that means they have behavior issues or learning deficits or come from difficult situations like poverty. We’re getting the full gamut here.

Don’t students who attend “alternative schools” have a bit of a reputation?

It’s true, a lot of times, that when the issues get here, we’re kind of doing patchwork. We’re doing our best to hold them together and either send them back to the middle school or the high school or to get their GED.

Are there kids who are especially hard to reach?

Yes, there are. With some of these kids, all they see is pain, poverty and aggression. It’s sad; that’s really the hardest part of the job.

You mentioned you act as a liaison with parents. How do you reach out to them?

At my parent conferences every Thursday, I encourage them to write down their concerns. I walk them through the levels that they can take those concerns to. They have due process, but that’s something a lot of minority parents don’t understand. I have to earn the trust of my families.

We try to make it clear that this is a school that’s going to take care of you. We’re going to make sure your child is safe. We stay in constant contact with a lot of our parents. And our students have my card: They can call me anytime, day or night.

Do they ever call?

Yes. Not all the time, but yes. And when I gave them my card, at first I was like, “Uh-oh.” But I’ve only been called out twice in the past two years after 10 p.m.

When they call, what are they asking for?

I help straighten anything out, from parents who are not happy about the bus stop to “We need food.” We have a food pantry right here, and I can pull something together and take it right over to them and hold them till the end of the month. We even keep clothes here at the school in case of crisis.

Parents struggle. You know, you’re a single mom, you’ve got four kids and you make $5.50 an hour. If you have a car, gas is what now? Probably be above $4 by summer. So can you imagine? You’re getting, what, maybe a dollar out of your paycheck?

What’s the best way to inspire these students and motivate them to learn?

The biggest job is to create real-time change for them. We have to find a hook.

What’s an example of a hook?

Awhile back, we had two of our kids involved with the Clean Water for North Carolina project. It was awesome. They showed up for work every day over in Shiloh. Two kids from public housing over there cleaning up the creeks. How powerful is that? They learned something. The potential is in there.

Also, last year we sent four kids from public housing—Team Eco—to Florida, where they got to swim with the manatees and drag the Gulf of Mexico to see what kind of plants and animals they’d find. It was an awesome opportunity for them. But you know something? It was $500 a clip for them to go.

So money’s a big part of it?

It’s big. One of the things that bothers me about Asheville—which is such a wonderful community—is that, when you’ve got an idea that’s a little “outside the box,” you can’t find anyone to help you with it.

Awhile back, I wrote a commentary about the fact that they raised $5 million for the new dog shelter here. I was like, “You kidding me?” Don’t get me wrong—I love my Brittany spaniel—but there’s a time and a place when we’re going to have to prioritize a little bit. We have to understand that we’re a community, and our kids are enough of a reason for us to come together.

You’re saying that kids need to see more of the world to know what’s possible for their own lives?

Dude, it’s environmental. Our kids aren’t going to go over to A-B Tech and explore culinary arts, or any type of med tech, radiologist. You know what I’m saying? They don’t understand that, because their environment is Hillcrest, Pisgah View Apartments and the mall. Period.

Aside from money, how can we—as community, as a place—reach out to these kids, these families, and help support them?

You can come in and tutor. You can mentor some young people. And you know what? I think it’s time for Asheville—I’m about to get real with you—to realize that the elephant’s in the room. I’m black, you’re white, let’s get over it. That’s the first thing we need to do. We need to start a healthy, real dialogue. They say it takes a village. Well, here’s our village. Let’s take care of some daggone kids. Let’s be there for each other. Let’s stop being so separate.

Can you share a success story?

A former student, a young lady, came in to see me. She’s in foster care now. And she said to me, “Big E, I’m doing so good.” And I know that I didn’t make that change—she has a lot of personal courage. And she told me that she was running track, making A’s and B’s in her classes.

It goes to show you that if you get the kids into a situation where they can do something, they’re so resilient that they can come back. Man, I’m telling you—they can do so well.

Just for the public record: Eric Howard is one of many heroic people in public education: ordinary people doing extraordinary things. The public is remarkably uninformed about the level of need of many of the students in our schools and the rewards and challenges of serving them. I suggest the public who really want to see great work taking place arrange a visit to the Asheville City Schools. Better yet, volunteer to work with our children to become part of the solution. You will not regret the time invested.

There are teachers here at RLC who do amazing things with these kids and who work extremely hard every day. Why aren’t some of these people featured in your paper? Most of the hard work at our school goes unnoticed by those outside of our school, even when we attain phenomenal results.

For example, our 8th grade LA teacher who had 100% of her students pass the Reading EOG last year. Find those results at another school in the state!

I really appreciate his passion for the kids. We are blessed in our system to have him. Along with Mr.Howard and my community it is my desire to continue to support, contiribute and encourage those who want all kids to succeed and be the very best.Thank you for working so hard with children who have such big futures!!!!

It extends beyond the classroom, though Dr. Grant and Big E are right the kids need more opportunity. Having had the distinct honor of being able to work with Big E and the students of Randolph I am fully aware of the potential they have. Take them up on thier advice and visit them sometime, and realize this. They are kids who are just as capable of sucess, love, and caraing as any others that are given the chance….

Congrattulations Big E, and the Randoplh Staff. I was proud to work with you…