Growing up in Franklin, Charles Clouse learned everything he wanted to know about farming. He didn’t like it—particularly the part where his father assigned him to hoe acres of corn.

So he escaped to Asheville, learned paint-and-body work and built a business called Kars and Kolors. His most important job skill might be imagination—being able to look at a wrecked vehicle and see how it can be salvaged. In fact, Asheville residents see his work on a daily basis, since one of his clients is the city’s police department.

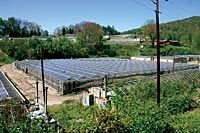

Now, through no fault of his own, Clouse has come into possession of one of the largest greenhouse complexes in the region. Buoyed by the same sense of imagination that serves him in the car-repair business, he seems destined to return to farming on a major scale.

“It’s such a beautiful place and it could be so productive,” Clouse says of the complex. “And I don’t want to grow flowers or use pesticides. I think it should be used to grow food.”

Not just any food, either. Through the years, Clouse has become a true believer in organic farming, and he is intent on restoring the abandoned facility as “an environmentally friendly business.”

Uphill battle

Kars and Kolors is located on Cowan Cove Road, just outside the city limits in West Asheville on Spivey Mountain. More important to this story, it is located directly downhill from the Hyman Young nursery. The late Hyman Young Sr. was a near-legendary grower of poinsettias with a production operation that employed up to 50 workers and shipped plants nationwide.

Walking around the abandoned facility today, the sheer scale of the complex is awe-inspiring. The soil-mixer drum, which was taken from a ready-mix concrete truck, tumbled the potting mix and unloaded onto conveyors, which, in turn, delivered the mix to a pot-filling machine made to feed into yet another conveyor. Some greenhouses used drive-through, heated loading bays for 18-wheelers so that Christmas-delivery schedules didn’t expose plants to winter weather. Multiple heating plants provide gas- or oil-fired steam heat, electronic controls open louvered glass or draw massive shades into place, and there is an electrical-power back-up generator that could run a small village. (With an operation that did a reported $5 million of business annually in flowers, one didn’t take chances on a power failure.)

Clouse reports that he had no trouble with his uphill neighbor until 1996, some years after Young had died and ownership had changed hands. Illustrating his story is page after page of snapshots in a photo album.

“The first major fish kill in my pond came in 1996,” Clouse says, adding that the pond is fed by a stream that flows down from the 46-acre nursery property. “Then a major oil leak started in 1997.”

He says he contacted the owners after each incident and was assured that the problems would be fixed. Seeing no results, Clouse contacted the N.C. Division of Water Quality in the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR).

“The state came out and said, ‘You’ve got a problem, we’re going to fix it,’” he recalls. “Nothing happened, but the greenhouse operations ended in 1999.”

The rainbow of oil continued to coat the pond, fish kills recurred and Clouse kept complaining.

“In 2000 there was a new person at DENR who came out to test the water, but there had been a storm and he said the flow was too high to get a meaningful reading, due to dilution. But I told him he should test anyway, since he was here. The result showed 900 times the legal limit for pesticides.” The photo record includes dead birds, wild mammals, a snake and, perhaps saddest of all, one of Clouse’s dogs.

According to DENR records, Hyman Young Greenhouses Inc. was fined $4,000 for water-quality violations on Sept. 18, 2000. But Clouse says the toxic runoff continued, and he finally contacted the federal Environmental Protection Agency, which advised him that his best option was to file a lawsuit for damages. “That’s how I got it,” he relates: He won the lawsuit and received the property as payment for the settlement imposed by the court.

“Professor Rick Maas came out from UNCA and looked it over in 2000 as well,” Clouse recalls. “Rick told me that pesticide pollution cuts in half each year, so that in three-to-five years, the ground would be considered clean.”

Furthermore, greenhouse plants are grown in potted soil on tables and the buildings are steam cleaned each year, so any lingering residues would presumably be out of contact with plant products.

Extension Agent Amanda Stone at the Buncombe County Center of the North Carolina Cooperative Extension agreed with Maas’ view.

“Sunlight biodegrades most pesticides, and some become inactive once they land on concrete or clay,” Stone notes. “The combination of sunlight and heat over time would render them inert.”

Clouse says an extension agent told him that the best way to speed the cleanup process would be to put the buildings back into operation, with fresh water flowing in to continue dissipation of whatever residue remains.

Mr. Fixit digs in

Starting in 2002, Clouse began a physical cleanup. The oil leak had been stopped and 30 dump-truck loads of oil-contaminated soil were removed as part of the legal settlement. There were thousands of flower pots, acres of plastic sheeting, abandoned truck heaters, propane bottles, pallets and cardboard boxes. Then came Hurricane Ivan and flooding that left several inches of mud in some buildings and piles of flotsam along the stream.

Slowly but steadily, the disorder was put right. Hired helpers cut down small trees sprouting up in some of the greenhouses, while Clouse replaced broken glass, fixed doors and pressure-washed some of the buildings. The largest projects included removing soil from a completely silted-up one-acre holding pond, building a sedimentation pond above it and cleaning up the pond on his original property below the nursery. The upper pond is the water source for some of the greenhouse systems.

Today three ponds are alive with fish, frogs and turtles. Migrating water birds visit and Clouse’s grandchildren jump in from grassy banks.

“The EPA told me an ‘all clear’ and the Buncombe County Health Department came in and said they don’t feel there is a health hazard,” he reports. Contacted by Xpress, DENR confirmed that the violation that resulted in the fine had been corrected and remediated.

“There’s people who want to build condos here, but what a waste that would be,” Clouse says with a grin. “You couldn’t afford the infrastructure today—it must amount to millions of dollars worth of buildings and equipment.” And while the site has breathtaking views, he asks rhetorically, “If I sell that view, what kind of view will I have?”

Because he knows next to nothing about running and managing greenhouses, Clouse wants to enlist others. He says he is open to any kind of arrangement, whether it is one business or dozens of small-scale farmers, a cooperative or multiple tenants.

And Stone, whose job description includes helping growers with commercial horticulture, greenhouses, nurseries and farm-business planning, is enthusiastic about the prospects. “I’d love to do what I can to help them get organized,” she says. “We are working on a Small Farms project in Buncombe County, to further prosperity and prevent loss of farms and farm acreage to development.”

“I’m not looking to make a lot of money here,” Clouse insists. “I just think that this facility could produce enough food to feed Buncombe County. I need to be able to pay for maintenance and taxes, but the main thing is to grow healthy, organic food locally. That is what I want to achieve.”

For more information about the greenhouses and their future use, contact Clouse at 280-8985, or Glenda Rice at 258-9263.

I find it ironic that Mr. Clouse is so gung ho for organic growing. I worked at Hyman Young’s from Mar. of 1973 until they closed the first week in June of 2000 ( not 1999 as stated in the article.) We would stand up on the hill and watch as Mr. Clouse burned aerosol paint cans, and possibly tires–it had to be something rubber because of the thick black smoke and the smell. You could hear the cans explode in the incinerator. He also had many junky cars sitting on the creek bank, and there is always leakage from such objects. Much of this took place after Mr. Clouse started action against the greenhouses. We tried to get the owner to call the EPA and report this, but he wouldn’t. And the friction between the two sides started well before 1996.

Yes, it was a magnificent place, all laid out over the hillside. Possibly one of a kind. And the view from the top was grand. I worked in some of the older houses that had been relocated there from Mr. Young’s father’s operation that had been closer in to town.

I have hundreds of photos of the place and most of the people who passed through during my 27 years there, so when I get nostalgic I can travel back.

I wrote a poem by the time clock on that last day. I wonder if Mr. Clouse was touched by it, or if he laughed? I would wish him luck, but I just can’t bring myself to do that.

I worked for Hyman Young duing the years of 1977 and 1978…it was a fantastic place…it’s where I still hold my growing roots and refere back to the grander of the operation. I am still in the business and I have some wounderfull photos of Hyman’s…I would like to see some if you could post them to me.

Regards,

Greg Newton

gpnewton1@yahoo.com

Back again checking. Yes, Place is still dear to me. I was always amazed, simply amazed at how nice it was. It was clean no weeds, no problems no fans making noises just the vents open in the cool mountain air cooling the plants and keeping the temperature is just right! Now we did do things the hard way there weren’t too savvy on the technology at that time. It was in the beginning of computers. Folks thought they were just a fad, I kept saying it’s not it’s not, it’s here!