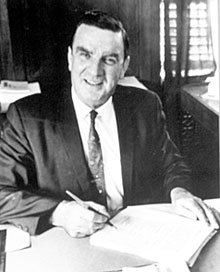

photo courtesy of the city of Asheville

Iron and silk: Weldon Weir, Asheville’s most famous city manager, kept his door open to residents in need — and an iron grip on their politics. His party machine is gone now, but the city manager is still the most powerful official in Asheville.

|

When incoming City Manager Gary Jackson takes the helm as Asheville’s most powerful official on June 27, he will oversee the city’s thousand-member work force and multimillion-dollar budget (see sidebar, “From Steamrolling to Bridge Building”). But when he begins tackling the issues facing Asheville today — the water system, the Civic Center, downtown development — he’ll find the fingerprints of his most famous (and most controversial) predecessor all over them. Weldon Weir guided this city through its hardest, poorest times while building a political empire unequaled here before or since. And in the process, he retooled the local power structure to serve his purposes.

Other public functionaries are often more visible. The police chief, the fire chief, the parks-and-recreation director, the public-works director, the planning-and-development director: These and other key city officials draw the hot spotlight of public attention whenever one of them signs off on a decision that affects local businesses’ profits or city residents’ lives. But every one of these movers and shakers answers to a single person, whom Asheville’s charter vests with the sole power to hire them, fire them, and tell them how to do their jobs: the city manager.

Like a corporate CEO who’s supposed to answer to a board of directors, the city manager is himself hired or fired by the men and women the voters elect to City Council. Yet there was a time, not so long ago, when Asheville’s unelected boss even chose the folks who would supervise him.

Just about everyone who lived in Asheville during the ’50s and ’60s has a story about Weir, who served as city manager from 1950 to 1968. His admirers speak of him in near-reverent tones, and even those who opposed his autocratic political machine praise the results he achieved. To a significant extent, modern Asheville is Weldon Weir’s legacy.

At the beginning of his reign, Weir lobbied successfully for building the 36-inch pipeline from the North Fork Reservoir into the city — a key component of the municipal water system that’s now being bitterly disputed by Asheville and Buncombe County. Ironically, Weir’s diversion of water revenues, which helped keep the city afloat financially while it was laboring to pay off its Depression-era debt, also helped create the crumbling infrastructure that still plagues the system today.

In 1955, county voters rejected a bond issue to build an airport. Two years later, Weir pushed through a city bond issue that gave us the Asheville Regional Airport. In the mid-’60s, Weir helped conceive the plans that led to the construction of the Civic Center a decade later. And in 1964, he secured millions of dollars in urban-renewal funds to redevelop a 75-acre triangle of downtown north of City/County Plaza and east of Market and Spruce streets. This 12-year project left in its wake a swath of sleek, parking-lot-encircled modern structures such as the Buncombe County Health Center and what is now the Renaissance Asheville Hotel — right alongside the blocks of funky, antique buildings that are the focus of today’s downtown revival.

But even greater than the mark he left on the city’s physical landscape is the way Weir reshaped its political terrain to center on the city manager’s office — which many observers say remains the pinnacle of local power to this day.

The problem-solver

Throughout the cash-flush days of the Roaring ’20s, Asheville was run by a mayor and two elected commissioners (of public works and public safety). Then came the Great Depression. In 1930, angry citizens forced the mayor and both commissioners to resign after discovering that they had illegally borrowed huge sums of money in a vain effort to keep the bank holding the city’s accounts from crashing.

In a referendum held the following year, Asheville voters approved a change in Asheville’s charter (later confirmed by the N.C. General Assembly) that placed the city under the council/manager form of government. This relatively new system — pioneered by Staunton, Va., in 1908 — empowered an elected mayor and city council to appoint a professional manager who would serve as the city’s chief executive officer — overseeing its day-to-day business, preparing and administering its budget, and hiring (and firing) its personnel.

The new system got off to a rickety start. Asheville’s first city manager — R.W. Rigsby, who had previously held comparable positions in Charlotte, Durham and Bristol, Tenn. — retired after only two years. The second, George Hackney, wound up being sued (along with the city council that had hired him) by Asheville’s creditors, who claimed that the city owed them its water revenues in payment of its massive debts.

The third city manager was a local Democratic Party mogul and former Asheville Times publisher named Pat Burdette. But he didn’t exactly throw himself into the job, as Margaret Simmons, Weir’s secretary, recalled years later for local historian Rob Neufeld. Burdette would get to work at 10 a.m., take a two-hour lunch, and leave at 4 p.m. The man who actually got things done was an ambitious 22-year-old whom Burdette promoted to public-works director immediately after his own installation as city manager in 1935. Fifteen years later, Weldon Weir took over Burdette’s job in name as well as fact. And in his two decades as city manager, Weir is credited with almost single-handedly pulling Asheville out of the prolonged financial spiral precipitated by the Depression.

This Asheville-born son of a sales executive turned dairy farmer was a tireless worker, those who knew him recall. Weekdays, he would rise at 5 a.m. and show up at the city garage first thing to give arriving employees his version of work orders — slips of paper bearing notes he’d made the day before and stuffed into his pocket. From the time Weir arrived in his office (generally around 8:30), he kept his door open to anyone who wanted to see him, writing down what needed to be done to solve petitioners’ problems on more slips of paper. And Weir would often return to the garage at 5 p.m. to check with the returning workers on the status of jobs he wanted finished that day.

“I still hear [this from] some of these old-timers that talk about Weldon: If you went to Weldon with a problem, it was taken care of,” says Bruce Peterson, who grew up in Asheville during Weir’s tenure and has been active in the Buncombe County Democratic Party for many years. “I mean, you didn’t get lip service — you got results.”

And not just bigwigs like Democratic Party power broker Don S. Elias (then the publisher of both the Asheville Citizen and the Asheville Times), or the executives at Wachovia Bank (which handled the city’s accounts and covered its most pressing bond debts after the Depression crash). What made Weir’s name legendary in this town was his genuine concern for the problems of ordinary city residents.

“If they needed fuel oil, if they had a fire at their house, he took care of people — he made sure they had what they needed,” remembers Peterson, and published biographies of Weir corroborate this.

Bruce’s wife, Carol Weir Peterson, is Weldon’s niece. Since her election to the Buncombe County Board of Commissioners last fall, she reports, many locals who recognize her name have told her stories about how her uncle helped them. “So many people said, ‘He was more my family to me than my family,'” she recalls.

Weir was even a pioneering force for racial equality, hiring minorities at a time when the South was still mired in segregation.

Meet the machine

But there was another side to the way Weir got things done. In an age when Western North Carolina’s mayors and sheriffs often ruled their little fiefdoms like backwater feudal barons, Weir operated a political-patronage machine that would have done Chicago Mayor Richard Daley proud.

It wasn’t Weir’s creation: He inherited it from Pat Burdette, who for decades had been one of the leaders of an entrenched Democratic Party syndicate that the newspapers called “the Burdette-Greene-Nettles organization.” The first partisan City Council elections, held in 1935, were swept by the syndicate’s candidates, who promptly hired Burdette — the head of the Buncombe County Democratic Party — as city manager, a post he held until passing the torch to Weir.

Weir ran the machine with a down-home touch. Every Saturday morning, everybody who was anybody — or who wanted to be — came to the basement of the Lance’s Produce warehouse on South Lexington to have hot dogs with Weir and his cohorts as they casually hashed political matters. Whether you were a teenager hoping for a summer job cutting grass at the cemeteries or a pillar of the community dreaming of a seat on City Council, the first thing you had to do was meet Weldon face to face and get his approval.

Bruce Peterson, whose first job as a youth was swinging a sling blade for the city Parks and Recreation Department, remembers the experience well.

“First thing they ask you is, how is you registered? How are your parents registered? Do you live in the city?”

If you or your folks weren’t straight-ticket Democrats, or you didn’t live in town, you didn’t stand a chance. And even then, if you weren’t a friend or family member of Weir’s, a hot dog was often all you’d walk away with.

In an article titled “Asheville Used to be Run Like a Family, and Things Got Done,” (May 1, 2004 Asheville Citizen-Times), Rob Neufeld quoted Weir’s close friend and right-hand man, Charlie Dermid, who said Weir’s motto was, “Never hire anybody if you didn’t know his grandfather.” Dermid, who attended school with Weir and worked with him early on at what is now Azalea Park, benefited from his powerful friend’s patronage for decades. At various times, Weir installed Dermid as parks director, police chief, director of public safety and director of public works.

Throughout the ’50s and into the ’60s, Weir in the city and Sheriff Laurence Brown in the county controlled access to every local elective office, deciding who would run — and, usually, who would win.

“Many people have told me, ‘I wanted to run and I went to see Weldon, and he told me no!'” Bruce Peterson recounts. “He said, ‘You can do it … but you won’t get support.’ He said, ‘We’ve got somebody in line for that.’

“I think it was a situation where today you’d say the tail’s wagging the dog — where the manager controls the [city] council. He approved their running for office, helped them get elected; they were all in this thing together, they depended on each other. It wasn’t an adversarial situation at all. That’s just the way it was. If you wanted to run, come see me.”

In those days, the South was overwhelmingly Democratic, and city employees were expected to vote for Weir’s men. But some say the machine was not content just to drive folks to the polls and hope for the best: Rumors still persist of impossibly lopsided precinct counts, and of votes cast by folks who never entered a voting booth (and we’re not talking absentee ballots here).

Many Ashevilleans opposed the way Weir operated, even if they liked him as a person. One of his most determined critics was local attorney Bruce Elmore Sr., himself a Democratic Party powerhouse at the state level. His son, Bruce Elmore Jr., is also an Asheville attorney who serves on the board of the state chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union. As a boy, Elmore Jr. saw through the eyes of his father (who’s now in his 90s) what a town ruled by patronage looked like.

“You couldn’t do much of anything politically without being on the right side. It may even have been more perception than reality, but people would have thought that, ‘Oh, if I want to get a loan from [a local bank], I probably ought to be friendly to the machine.’ So a lot of folks who weren’t political would have given lip service to the machine.

“If you had a business, and you had to have delivery people double-park every now and then to deliver, you wouldn’t want to be against [the machine] because folks might get towed. They would have worried, whether it would have actually happened or not.”

If your bar had a jukebox owned by a rival of one of Weir’s relatives, your customers would be repeatedly arrested for DUI by the police, remembers Elmore — because the city manager controlled the police chief.

But whatever Weir’s enemies thought of his methods, his chief critic never believed that the powerful city manager was motivated by greed.

“My dad never thought that [Weir] did it for gain,” recalls Elmore, adding, “He just wanted control; power. And he had it.”

The end of an era

But in the perennial struggle to stay on top of the political heap, Asheville’s alpha male finally lost a key bout with a powerful rival. In 1964, when City Council voted to introduce cable television, Harold H. Thoms, who owned local television stations WLOS and WISE, was one of the principal bidders for the contract. Weir, however, convinced Council that the city should own and operate the cable infrastructure as a public utility (it would have been the city’s only income-generating utility, other than water), and successfully fended off Thoms’ efforts to acquire the contract.

The next year, Thoms sweetened his deal, promising to direct 20 percent of the cable system’s profits to the Asheville Orthopedic Hospital, which he served as board president (it’s now known as Thoms Rehabilitation Hospital). Yet Weir and City Council chose an out-of-state cable operator who offered Asheville a smaller cut of the profits than Thoms had, but who promised to turn the whole system over to the city after 20 years.

In 1967, though, Thoms got his way. Weir’s own Council turned around and handed the local TV magnate a contract to install and operate Asheville’s cable-TV network. The still-controversial document essentially gave Thoms a 35-year monopoly on the city system.

“I think it just sort of signaled that his era was over at that time,” says Elmore. On Sept. 1, 1968 — mere days after the riots at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago — Weir announced his resignation as city manager. And in the Council elections the following spring, a slate of outsiders beat the machine, as Republicans took control of City Council for the first time ever. The voters also elected Asheville’s first black and first female Council members.

The new Republican mayor was Dr. Wayne S. Montgomery — the director of the cerebral-palsy clinic at Thoms’ hospital.

Weir lived until 1987, remaining a respected elder statesman in the local Democratic Party. But he never again held the kind of power he’d wielded as Asheville’s city manager.

The more things change …

Today, as the 11-year tenure of City Manager Jim Westbrook winds down, political parties play only a limited role in Council elections, which have been nonpartisan for years. City officials now run a many-layered, multimillion-dollar bureaucracy, and the Saturday-morning klatches over hot dogs are history.

But what hasn’t changed much — because it’s built into the city’s charter — is the lopsided balance of power that drives Asheville’s strong manager/weak Council form of government. While elected officials take the heat for unpopular decisions, it’s often the city manager who, behind the scenes, has done much of the actual deciding.

“Any time you have a council/management-type situation, council does set policy, but we’re elected people, and we really don’t have the background in public administration that a manager does,” observes Council member Jan Davis. “So we have to rely very heavily on what they say. If you have confidence in that manager, it helps a great deal.”

Brian Peterson (no relation to Bruce or Carol), who served on City Council from 2000 to 2004, was one of several Council members who clashed with Westbrook (and nearly fired him) in 2003. Peterson, who says he has no plans to seek a seat on City Council again, spoke candidly with Xpress about his experience of how the council/manager system plays out.

“It’s a bit of an unequal playing field, because — it’s like running the military, you know? The president’s the commander in chief, but the general actually’s got command of all the soldiers on the field, and so the policy might be we’re not going to abuse prisoners in Iraq, but the general lets it happen.

“Council’s a part-time job,” notes Peterson. “Everybody [who isn’t retired] has other work, has families; you don’t have time to be an expert on everything that comes before Council.”

Echoing Davis, Peterson says: “You end up relying very, very heavily on staff, and some have the view that — they’ll sort of give staff a huge benefit of the doubt. Whatever staff says must be right, unless there’s some overwhelming evidence or reason why you’re going to disagree with them.”

With a staff of 20 and the entire city work force to command, the city manager has far more resources at his or her disposal than Council members, who are lucky to have a handful of volunteers to help them out.

“There are certain duties that Council legally has to do — you know, approving a rezoning — that actually takes a vote of Council. But the process of getting it to Council is controlled by the city manager, and what staff recommends is controlled by the city manager. The information that comes to Council is controlled by the city manager.

“Council in the vast majority of cases is going to follow what staff recommends, and the city manager can tell staff what to recommend,” Peterson emphasizes. “So even though the city manager — maybe it’s a big rezoning — sits there and doesn’t say a thing, he probably has shaped what staff has recommended. And sometimes he plays sort of coalition-building politics to put together a majority of Council to vote for something that he wants.

“Council gets the blame for stuff, but it’s typically the city manager who’s been really running stuff. Or [if] not him directly, then staff under his direction. But he stays out of the limelight — doesn’t talk much at Council meetings. He talks before Council meetings; he talks with members one to one, or in groups of twos and threes. And he very much stays out of the limelight, so if there are people who are unhappy, they’re unhappy with members of Council and not with him.”

From Weir to Westbrook, Asheville’s unelected bosses have exerted a tremendous influence on the city we live in. Now it’s Gary Jackson’s turn to put his stamp on the Asheville of the coming years. And though it remains to be seen what his impact will be, in the end, notes Council member Davis, “You just have to have a lot of faith that person is going to do what you want them to do.”

UNCA senior thesis by Hayes C. Martin, Jr. entitled “J. Weldon Weir and Asheville Machine Politics” (dated November 2001) should offer more information. Ramsey Library Special Collections holds bound volumes of senior papers from 1995 to the present.

For more on UNCA’s special collection of student research papers, visit http://toto.lib.unca.edu/sr_papers/history_sr/default_UNCA_history.htm