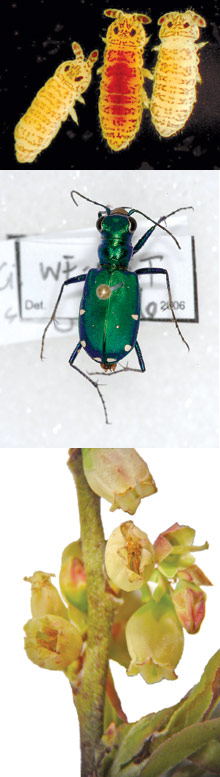

The Lamar Alexander springtail (Cosberella lamaralexanderi) is a small, insectlike creature patterned with calico dots. Named for the senior senator from Tennessee, it is partial to dead leaves and plays a vital part in the whole forest food web. And here is the clincher: Until 2006, the Lamar Alexander springtail was completely unknown.

Of course, the same could be said about the beetle known as Anillinus langdoni, the wasp known as Orthogonalys bella, the fungus known as Amoebidium appalachense and the water bear known as Doryphoribius smokiensis. All of these species inhabit the more than 800 square miles of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park—and all were discovered within the last decade.

“We have almost 900 species new to science in the past 10 years,” says Todd Witcher, executive director of Discover Life in America. They include 74 species of butterflies and moths, 70 species of algae, 41 species of spiders, 37 species of fungi, 34 species of beetles, 27 species of crawfish and crustaceans and 19 species of bees.

All this in the nation’s most-visited national park (nearly 10 million people each year); the one with the worst air-quality; the one that sits within a day’s drive of a good portion of the nation’s population. All it took was a little looking.

Witcher’s group, a Gatlinburg-based nonprofit, is the managing agency for the All Taxa Biodiversity Inventory, an ongoing study with the ambitious goal of cataloging all life forms within the park’s boundaries. Begun in 1997, the wide-ranging inventory, funded by private nonprofits and the National Park Service, not only points up what we don’t know about the Smokies—it tells us a good deal about what we stand to lose there.

“If you’re a business and you don’t have an inventory, it’s hard to manage your product,” notes Witcher. “The same goes for the park. It’s hard to manage—and, in this case, conserve—species when you don’t know they exist.”

A place for us

A number of factors have enabled the Smokies’ astonishing biodiversity. In strict geographic terms, the mountains’ northeast-to-southwest orientation made the area an escape corridor for species driven south during North America’s last several ice ages. As glaciers advanced over much of the continent, the Smokies were spared, serving as a reservoir of plant and animal life that could help repopulate it once the climate warmed.

The mountains’ complex topography—ranging from frosted peaks to deep coves; swift streams to dry, south-facing bluffs—offers specific niches for thousands of species. And it’s long been known that the Smokies host more tree species (130) than all of northern Europe.

In a sense, the park—dedicated in 1940—was established for the trees. By the 1930s, the logging that had begun in the late 19th century was quickly stripping the Smokies of their cloak of woods. Even so, the vertiginous topography kept some areas beyond the reach of loggers. Today, more continuous old-growth forest exists here than anywhere else in the Eastern United States.

Under the microscope

Since the All Taxa Biodiversity Inventory’s inception, hundreds of scientists have participated, from institutions across the country and around the world.

What makes the study unique, however, is its reliance not only on professionals but also on “citizen scientists”—adults, children, students, retirees—who are trained to seek out new life in the park and to determine the density of those species already known.

That’s what attracted Candler resident Kevin FitzPatrick to the project. A photographer by profession, FitzPatrick has devoted many unpaid hours to the cause.

“In his book The Creation, E.O. Wilson said that we’ve got about 6,000 scientists worldwide doing this sort of work,” notes FitzPatrick. “That’s just not enough people on the ground. We need citizen scientists to really get things going.”

After completing their training, volunteers wade streams to gather water samples. And during special events called “bio-blitzes,” scientists and volunteers descend on the park in tandem, searching its furthest reaches for unique species. One of the volunteers, a 13-year old boy, brought to light an insect that scientists had never seen before.

But even for kids who aren’t lucky enough to find a new species, the biodiversity inventory can be an exciting learning opportunity, says FitzPatrick. “There’s a huge component of the ATBI that gets kids involved in science and in nature,” he explains. “Because it gets them out of the classroom and into the water and the woods, and they’re able to understand nature in terms that they never have before. To me, that’s the future of science.”

One realm of study with almost limitless promise is microbial life. “There are estimates that a pinch of soil from a pristine environment could have a billion bacterial cells in it—and potentially a million species,” notes Sean O’Connell, who teaches microbiology at Western Carolina University.

Each year, O’Connell takes groups of graduate and undergraduate students on lab trips to the Smokies as part of their course work; back at school, they culture their samples and grow them, looking for previously unknown bacteria. Other samples are targeted for DNA sequencing. If a given bacteria’s DNA proves to be 85 percent unique, says O’Connell, it can confidently be called new. Over the years, more than 250 of O’Connell’s students have been involved in the work.

Although most bacteria in the park stay busy decomposing organic matter, recent study is revealing other roles. For instance, O’Connell and his students have looked at the bacteria associated with the Eastern hemlock, a species now imperiled by the hemlock woolly adelgid, an exotic insect.

“We have some idea about what chemicals the hemlocks are providing to the microbes, but less of an idea about what the microbes are providing the hemlocks,” he explains. Some bacteria species, he adds, probably convert atmospheric nitrogen to an organic form the hemlocks can use.

A tardigrade gold mine

But the park’s smallest residents may hold other surprises as well. Besides giving dirt its characteristic smell, the great numbers of bacteria found in soil, notes O’Connell, have also been tapped by the biopharmaceutical industry for their antimicrobial properties. It’s not unreasonable to assume, he says, that the Smokies might host a bacterium or two that could have wide application in solving human medical problems.

“There’s so much more out there that we have to learn,” he observes. “Really we’re just limited by our imaginations in finding a use for these things.”

Warren Wilson College professor Paul Bartels is also studying the microscopic world within the park, in conjunction with East Tennessee State University professor emeritus Diane Nelson, a group of international researchers, and nearly 30 Warren Wilson undergrads. An invertebrate zoologist by specialty, Bartels and his colleagues have identified 73 new species of “tardigrades,” or “water bears” in the Smokies since 2001—18 of them considered new to science.

Named for their stubby, bearlike build, tardigrades are small: The largest by far is only 2 millimeters long. They keep the company of rotifers and nematodes in the skim of moisture found around creek sediments and among mosses. In that world beyond sight, tardigrades are dominant, says Bartels, and they may serve as a vital link in the food chain between microbes and insects. Still, before the inventory, both their role and their abundance in the Smokies remained more or less unknown.

“There had only been one published record of tardigrades from the Smokies before we got started,” says Bartels. “[The researcher] just sort of swung through the area and found three species of tardigrades. That was all we knew.”

“It’s been a gold mine for undergraduate research,” he continues. Associated grants have enabled Warren Wilson College to expand its science facility to include a state-of-the-art microscopy lab, and the school’s involvement with ATBI, he says, “has revealed a million avenues for further research.

“This whole microscopic world is really diverse, really important—and we know nothing about it,” says Bartels. “This study is a perfect platform for getting people excited about the fact that there’s a whole world of life out there that has yet to be discovered.”

If a shrub falls…

Besides revealing nearly a thousand hitherto-unknown species in the park to date, the biodiversity inventory has also documented more than 6,100 species that were previously unrecorded in the Smokies.

One of these, the velvet-leaf blueberry, became the 5,000th species tallied by the study when it was found in 2006. Existing in small numbers in the park (and only at high elevations), it must tussle with ozone pollution, acid rain and the mounting threat of non-native plants in order to survive.

Roughly 10,000 living species are now known to exist in the park—and scientists believe that perhaps nine times as many have yet to be found. Park officials have documented more than 200 species of birds, 66 species of mammals, 50 species of fish, 39 species of reptiles, and 43 species of amphibians in the Smokies. In addition, the park is known to shelter nearly 1,500 flowering plant species and more than 4,000 species of nonflowering plants. Microscopic creatures account for the rest.

Recognizing this, the park was designated an International Biosphere Reserve in 1976 and was certified as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1983. Since then, however, development around the park has increased dramatically, and worsening air quality and other environmental threats have taken their toll on this island of exceptional diversity.

Enter the All Taxa Biodiversity Inventory. The first project of its kind, it has served as a model for a host of others both here and abroad. Similar projects are now ongoing at Yellowstone, Yosemite, Death Valley and Mammoth Cave national parks and at Point Reyes National Seashore in California. Concerned scientists, including park biologists, came up with the idea; planning began in 1997, and in 1998 Discover Life in America was formed as the coordinating agency.

Donations from nonprofits including the Friends of the Smokies and the Great Smoky Mountains Association have provided the primary support for the inventory, with additional funds coming from corporate and private donors. Witcher says he expects contributions from the first two groups will diminish in the coming years, requiring a search for new funding sources.

And given enough time, the study may see a point of diminishing returns, Witcher concedes. Biologists call this the “species effort curve”—a formula that predicts the amount of searching required to find a new life form. But with sufficient funding and the continued interest of both professional and citizen scientists, Witcher believes the inventory will continue to pile wonder on wonder.

“There may be something hidden in the park that we otherwise might not know about,” he maintains. “A cure for cancer, for instance. Granted that’s an extreme example, but it goes to show that there is a lot to be learned still.”

What gets lost, says Witcher, is the ecological importance of any given organism. While human beings tend to be seduced by the polar bears and wolves of the world—what ecologists like to call “charismatic megafauna”—this overlooks the millions of species that underpin the system, the unseen “heavy lifters.”

“A water mite may not be as big and spectacular as a bear, but it is probably just as important in the whole scheme of things,” Witcher asserts.

Consider, for example, the “fly blitz” held at the park recently. “I told my wife about it, and her first question was, ‘Why would anyone care about flies?’ and I didn’t have an answer,” says Witcher. “But what I didn’t know at the time was that flies are considered the second-most-important group of pollinators on earth. Well, we’re having trouble with our domesticated bees these days, and there may be a need to know more about flies. They may fill a niche that develops from the loss of bee species.”

In that sense, the project’s work has never been more urgent.

“There are lots of threats to the park in terms of development, acid rain, invasive species, global warming,” he notes. “All of those things are changing the park—in some cases drastically. It’s important to have a base line to let us know how the park is changing and what we’re losing. It’s not just a count for the sake of counting.”

[Freelance writer Kent Priestley is based in Knoxville.]

Volunteers search a meadow in the Smokies for insects…

Usually, if you just stand there, the insects will find you!