Ray Russell watched in awe as the howling power of the Blizzard of ‘93 paralyzed Western North Carolina with as much as 3 feet of snow and near-hurricane-force winds. But while “the storm of the century” kept area residents shivering in the dark for days, it also fired up Russell’s long-standing fascination with the weather.

The storm hit just two years after Russell moved to Boone to pursue his career as a professor of computer science at Appalachian State University, about 75 miles northeast of Asheville. And having witnessed the blizzard—and having noticed a lack of reliable weather data for WNC’s high country (the ASU campus sits at 3,266 feet above sea level)—Russell began publishing local forecasts in winter on his university Web page.

The mountain weather captivated Russell, who’d dreamed of being a meteorologist as a child. “[It] was so fascinating: the fog, the snow, the cold, the wind. Especially in the mountains, it just controls everything you do. I’ve called it our most valuable natural resource up here, and I think that’s true,” Russell says.

In 1998, Russell’s wife gave him a Christmas present that would change everything—a simple backyard weather station that could record rainfall, temperature and wind. Around the same time, the Internet was beginning to take off. For Russell the computer whiz and Russell the weather geek, it amounted to the perfect storm. He started posting his weather data on his Web site, along with his forecasts—which quickly became required reading among ASU students.

Russell appeared on a radio show and found himself being recognized at area restaurants: A local celebrity was born.

Ten years later, Ray’s Weather Center employs five meteorologists who keep tabs on 50 weather stations perched atop schools and businesses around WNC that deliver real-time data to the company’s Web site. The coverage area extends from Boone south to Hickory, including Asheville, Wolf Laurel and Waynesville to the west. They’re working on setting up a new station in Sylva and hope to add still more around the region.

Online, Ray’s Weather garners 150,000 to 200,000 unique visitors a month, reports meteorologist Jeff Cox, the outfit’s lone full-time employee. That Web traffic is increasing, says the Asheville-based Cox, who previously served as chief meteorologist for the Fox TV affiliate in Macon, Ga. The company, adds Russell, is also working on adding new online data tools to give users more useful weather information.

What began as one man recording the weather in his back yard has grown into a full-fledged Internet company that’s looking to grow. But it’s all done with a dash of homey style: The company logo features a caricature of Russell, and the forecasts occasionally mix in a little social or political commentary with the discussion of valley frosts and high-pressure systems. For example, the Oct. 2 forecast for Asheville (the day of the vice presidential debate) began like this: “The weather is so easy today, even a vice-presidential candidate could do it.”

Working the weather

On any given day, Ray’s Weather has its first forecast posted by 7 a.m., says Cox, synthesizing on-the-ground reporting from the weather stations, computer modeling, and lot of back-and-forth e-mails among staffers.

“There is a lot of science involved,” he notes. “You have to know the physics of the atmosphere. You have to know that dry air warms and cools faster than moist air. But there’s some art there, as well: We didn’t learn what we do overnight.”

The organization touts the fact that its six-person crew (including Russell) has more than 100 years of collective weather-forecasting experience. Three staffers are graduates of UNCA’s atmospheric-sciences department, which is known for turning out smart meteorologists.

The forecasts are updated at noon and again at about 6 p.m. “Especially with an Internet-based company, you’ve got to keep your data fresh,” says Cox. “We’re updating three times a day, seven days a week.”

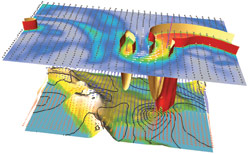

The forecasters use the same computer models as the National Weather Service, one of six agencies that make up the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The weather service provides a wide range of information through an array of national and regional centers, as well as local weather-forecast offices. The agency can also bring radar and satellite imagery to bear, along with a network of amateur weather-data collectors.

The big difference between the federal agency and Ray’s lies in their respective forecasts’ specificity and style, says Russell.

“I do not want this to be construed as critical of the National Weather Service,” he emphasizes. “I know a lot of those guys; they’re bright, and they have good tools, and what they do is far superior to what they were doing in the mid-‘90s, when I got interested. But the National Weather Service forecast is going to be a wholesale forecast, given the large area they cover.”

Ray’s Weather, on the other hand, wants “to add more specificity to the forecast. We want to say it will rain a quarter of an inch between 2 p.m. and 4 p.m. And we want to deal with microclimates more specifically. When snow hits, we want to say northern Buncombe County will get 2 inches and southern Buncombe County will get none.”

Then there’s the matter of style. When he first started, says Russell, he would often include liberal doses of personal commentary in his forecasts. After all, it was mostly being done to give him a creative outlet back then, he notes. But even today, the personality remains, albeit in toned-down fashion.

“We don’t want to be silly in the sense of getting in the way of the forecast,” says Russell. “We just want to make it interesting; we do try to have fun with it.”

Getting it right

Any discussion of weather forecasting inevitably leads to the question of accuracy—a touchy subject within the industry.

Jeff Masters is director of meteorology for Weather Underground, perhaps the granddaddy of independent, Internet weather services. In 1991, when Masters was a doctoral candidate at the University of Michigan, he wrote a computer program to display real-time weather data. Today, Weather Underground has a network of 10,000 personal weather stations on the ground and a Web site that has embraced user-generated content such as weather photos and blogs.

First and foremost, he notes, the National Weather Service posts no data on the accuracy of its forecasts. And though the agency’s computer models have “improved significantly” as computing power has increased, says Masters, there’s still room for improvement. The federal agency’s main computer model, for example, is not as good as the main European model, he maintains.

“I think a lot of the private groups do better than the National Weather Service. They wouldn’t be in business if they didn’t,” he says. In particular, “Some local offices do a better job of long-term forecasting” because of their combination of local knowledge and computer modeling.

At Ray’s Weather, meteorologist Cox cites recent predictions to make that very point. On Sept. 21, the National Weather Service’s Asheville forecast for Sept. 26 called for a partly cloudy day with highs in the lower 70s. Ray’s Weather, meanwhile, was forecasting lots of clouds, a chance of rain and a high near 70. A day later, the NWS was forecasting a mostly cloudy day with highs in the lower 70s; Ray’s Weather was predicting cloudy weather with rainy periods and a high of 68. In fact, the high temperature on Sept. 26 was 63 degrees, and there was nearly half an inch of rain. Cox says the example clearly shows that Ray’s Weather was calling for rain and more cloudiness several days ahead of the national forecasts.

In mountainous areas, weather forecasting—always dicey—becomes particularly tricky. “Mountains can act like a barrier, and forest terrain can create friction,” explains Alex Huang, a professor of atmospheric science at UNCA. “This creates more extreme temperature and pressure changes.”

That’s why the weather on top of Town Mountain can feel different from what’s happening downtown. Temperatures are typically lower at higher altitudes, and fog is often more dense both higher up and in heavily forested areas.

“Since Asheville’s weather forecasts come from the airport, which is 20 miles from downtown, there are always going to be differences,” says Huang. “When I check the temperature in my back yard, there’s usually a 3- or 4-degree difference from the airport.”

Stretched thin

The mid-1990s saw a major reorganization of National Weather Service offices aimed at making them more geographically cohesive. As part of the big shift, a nationwide Doppler radar network was installed, says meteorologist Larry Lee of the weather service’s forecast office at the Greenville-Spartanburg International Airport in Greer, S.C..

Up till then, forecasts for the entire state of North Carolina had come out of the weather service’s Raleigh/Durham office. A small office at the Asheville Regional Airport issued local warnings and prepared adaptive forecasts based on the Raleigh reports, he recalls.

“It was very taxing and demanding to cover the entire spectrum of weather events for the entire state,” Lee says about the former system.

When the Doppler radar system was installed at the Greenville-Spartanburg office, the Asheville office closed, although automated observation equipment at our local airport still collects data.

“Once we were responsible for smaller areas and had much more sophisticated technologies, we were able to provide much better service,” Lee reports.

Besides the technological improvements, he notes, the Greenville-Spartanburg forecasting office collaborates with a number of other organizations, including UNCA’s atmospheric-sciences department and ASU’s geology department. They also work with weather-forecasting offices in Mooresville, Tenn., and Blacksburg, Va., to develop forecasts for the mountains.

“Working with people doing academic research really helps our understanding of mountain weather,” says Lee.

“There’s still a lot we don’t know about weather. It’s a very, very complex science. That mystery, and wondering what’s going to happen next, is part of what keeps people interested.”

Future looks bright

Russell sees sunny days ahead for his company. The goal for Ray’s Weather Center is to expand its coverage area through partnerships with local schools and businesses. There are also plans to create new data products for the Web site, says Russell. “We plan to work on a comprehensive water-management site and be the single source for stream flows, lake levels and rainfall data,” he reports, jokingly noting that this year’s drought has to end sometime. “We want to find data products that people will find useful.”

And keeping a local feel to it all remains a priority, Russell says.

“We want the site to represent Western North Carolina in every respect. We want it to be an outlet for nonprofit groups, and we take pride in helping small businesses advertise. We really try to be an outlet for the region.”

[Additional reporting by contributing writer Anne Fitten Glenn. Jason Sandford can be reached at 251-1333, ext. 115, or at jsandford@mountainx.com.]

Hummmmmm… No mention from our pro-meteorologists regarding chem-trails? Here some links to get you started;

http://carnicom.com/

http://bariumblues.com/

We are still breathing…ah…