In the weeks after John F. Kennedy won one of the closest presidential elections in American history, Kennedy’s father asked the president-elect to seek an audience with famed evangelist Billy Graham. Kennedy balked at the request. Graham had supported Kennedy’s opponent, Vice President Richard Nixon, in the race. Furthermore, Graham’s father-in-law, L. Nelson Bell, had declared Protestants to be “soft” on Catholicism and had participated in a meeting of Protestant clergy that questioned a Catholic’s fitness to serve as president.

Kennedy was understandably wary of Graham, but he eventually acceded to his father’s request. In December 1960, Graham and Kennedy played a round of golf together, posing for photos in natty sport coats. For the Kennedy camp, those photos were priceless. Graham’s approval signaled to many Protestants that Kennedy could be trusted to lead the nation.

Editor’s note: Doing it by the book

Montreat, N.C.‘s most famous resident ranks among the most widely known religious leaders worldwide. For more than six decades, the Rev. Billy Graham‘s evangelical mission has touched the lives of untold millions around the globe.

Two new Graham biographies once again shine the spotlight on this most public of public figures. Given Xpress’ local-news mission, covering them seemed a natural—except that the author of one of those volumes, Cecil Bothwell, is also a staff reporter here. Although the book is an independent project that has no connection with Mountain Xpress, its author’s status raised some challenging questions about where the boundary lies between reporting the news and promoting one of our own.

Wanting to be fair to both Bothwell and our readers, we decided to bring in an outside expert who could knowledgeably review both books—and let the chips fall where they may. Seth Dowland, who holds a doctorate in American religious history from Duke University and teaches in the school’s writing program, seemed a good fit. Here’s his take on two attempts to characterize the political life of one of Western North Carolina’s most influential residents.

In hindsight, this story seems even more remarkable. In 1960, Graham was 42 years old. He hailed from a religious tradition, Southern evangelicalism, which had not exerted significant political influence for more than a generation. His crusades had brought Graham worldwide fame, but he stated repeatedly that his mission was to save souls, not to traffic in politics. And when Graham did wade into politics—which happened increasingly—he betrayed a deep fondness for Nixon. That Kennedy would place high priority on courting favor from a Nixon-supporting Southern evangelist tells us something about the kind of power Graham had amassed during the first decade of his public ministry.

But at what cost?

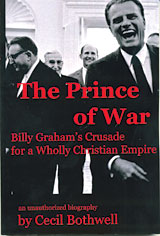

That question occupies center stage in two recent biographies of Billy Graham: The Preacher and the Presidents: Billy Graham in the White House (Center Street, 2007) by Time magazine columnists Nancy Gibbs and Michael Duffy, and The Prince of War (Brave Ulysses Books, 2007) by Mountain Xpress reporter Cecil Bothwell. The books are quite different, as a glance at their respective covers reveals. Gibbs and Duffy’s volume features a picture of an older Graham in a posture of prayer, surrounded by the presidential seal. In the reflected glare of the presidency, the image suggests, Graham fell on his knees before God. His relationship with the powerful did not derail his focus on God.

In contrast, The Prince of War features a black-and-white photograph of Graham laughing inside the White House during Lyndon Johnson’s administration. Onlookers smile, as if Graham has just delivered the punch line of an inside joke. He appears no different from the politicos around him. If the cover of The Preacher and the Presidents displays Graham as humbly reliant on God, The Prince of War depicts Graham’s smug satisfaction with his access to power. Indeed, he appears to have sacrificed his faith on the altar of the American presidency.

Chaplain to power

Gibbs and Duffy narrate Graham’s rise to power as the story of an overeager but well-meaning preacher who did wonders for the powerful men to whom he ministered. Especially in the early part of his career, Graham comes off as a striver who was keen on winning audiences with presidents and who fancied himself something of a political adviser. Some of the presidents Graham counseled counted on the evangelist to take the pulse of Christian voters. Others tossed him political crumbs that had little relevance to policy-making. In both cases, say the authors, Graham maintained a consistent message that elevated individual salvation over political calculations. He liked playing politics but knew that preaching the gospel was his real game.

Presidents loved Graham because he seemed utterly committed to the saving of souls. As Gibbs and Duffy explain, Graham’s intimacy with so many presidents hinged on their belief that he posed no threat to them politically. Accustomed to dealing with men and women intent on wrangling favors and concessions, presidents relished Graham’s seeming innocence. He demanded few favors and offered both political and spiritual support in return.

The chief success of The Preacher and the Presidents lies in its attention to the pastoral aspect of Graham’s ministry to White House occupants. While many authors have noted how presidents have used Graham for political advantage—a reality Gibbs and Duffy do not ignore—few biographers have demonstrated how important Graham was in many presidents’ spiritual lives. Graham connected with presidents. As the world’s most famous evangelist, he understood the perils of fame. He knew that presidents wanted affirmation, not judgment. He never attacked them in public and shied away from chiding them in private. Critics painted Graham as an enabler, unwilling to speak truth to power. Graham, however, believed he was uniquely suited to ministering to presidents, and he refused to jeopardize that ministry by calling them on the carpet. As a result, presidents from Eisenhower to George W. Bush relished his pastoral attention. Lyndon Johnson invited Graham to the White House at some of the most trying times of his presidency; Ronald Reagan turned to Graham for support when the Iran-Contra scandal flared up; the Clintons counted on Graham to shepherd them through the Monica Lewinsky ordeal. The intimacy Graham forged with presidents led at least three of them—Johnson, Nixon and Reagan—to ask him to preach at their funerals.

Gibbs and Duffy also suggest that Graham’s persistence in seeing the good in others allowed him to maintain a faith in the honor of his presidential friends. Graham’s naiveté cost him on several occasions, most notably as he doggedly defended the integrity of Richard Nixon during most of the Watergate crisis. But Gibbs and Duffy largely absolve Graham of blame for his mistaken appraisal of Nixon. While they say that Graham was “complicit” in Nixon’s Machiavellian schemes, Gibbs and Duffy point out that he knew nothing of the worst “White House horrors” and “could not imagine” that Nixon would lie to him. They praise Graham’s handling of the Watergate aftermath, when the evangelist encouraged Gerald Ford to pardon Nixon and made repeated attempts to counsel the disgraced former president. Gibbs and Duffy see Graham as susceptible to the temptations of power but fundamentally goodhearted, an honest preacher of the gospel to men who needed to hear the message.

Sinful witness

Cecil Bothwell thinks otherwise. Bothwell opens his unauthorized biography by describing his reaction to the March 2002 publication of several recordings from the Nixon White House. One of these recordings captured a 90-minute conversation in which Nixon and Graham discussed Jewish influence on the American media. Graham lamented the “stranglehold” he felt Jews maintained over the national media, saying that Jews “don’t know how I really feel about what they’re doing to this country.”

Graham’s stark bigotry demands explanation. Gibbs and Duffy admit that Graham was “lost in the toxic fumes” of the presidency, and they note his well-publicized contrition in the wake of the recording’s publication. In Gibbs and Duffy’s retelling, the “Jew conversation” represents an unusual step out of character for Graham, a moment when he made a terrible mistake and departed from his core principles. Bothwell, on the other hand, sees the conversation about Jews as a revealing window into Graham’s soul. Bothwell’s Graham is neither naive nor goodhearted. Rather, Bothwell gives us a Graham who shrewdly managed his public image while offering religious blessing to both prejudice and war.

Some of Bothwell’s critiques deserve more attention than Graham’s supporters tend to give them. The preacher’s relationship to the civil rights movement, for example, is more complex than is often acknowledged. Graham deserves credit for desegregating his Southern crusades as early as 1952. But in the tense atmosphere of the 1960s, Graham denounced civil rights agitators. And his endorsement of “law and order” meshed nicely with Nixon’s “Southern strategy,” a campaign tactic designed to attract Southern whites to the Republican banner by denouncing liberal activists. This involved playing on whites’ racial fears in the wake of desegregation, and Bothwell rightly highlights how Graham’s rhetoric favored authority over racial justice.

Bothwell also exposes some of Graham’s more deplorable attitudes toward war. Notably, in 1969, Graham recommended that Nixon “bomb the dikes” in North Vietnam. Destroying dikes would, as Graham noted, demolish the North’s economy. Destroying dikes is also a war crime. Some estimates suggested that bombing the dikes in Vietnam would result in 1 million deaths. Graham’s endorsement of such an action displays a shocking failure in moral judgment. And while this instance marked a nadir in Graham’s advice to Nixon, he avoided asking hard questions about the morality of the Vietnam War until the conflict had nearly ended. For a variety of reasons, Graham thought it best to profess his faith in the judgment of the powers that be. One might expect more from someone who exerted spiritual authority over the most powerful men in the world.

In fact, Graham realized this as his career progressed, though Bothwell fails to note the development. By the late 1970s, Graham was stumping for Jimmy Carter’s Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty, earning him the enmity of political conservatives. Graham bucked Reagan’s advice and accepted a Soviet-sponsored invitation to preach in Moscow in 1982. He told the president that he sensed a spiritual revival behind the Iron Curtain and renounced his earlier support for nuclear buildup. Bothwell merely notes that Graham refused to testify before Congress about arms limitation. But since the mid-‘70s, the evangelist’s record on arms control is unequivocal. To suggest that Graham was somehow shirking the topic distorts the historical record.

Overall, Bothwell allows Graham no room to grow and change. He focuses most of his book on the evangelist’s early career, when Graham’s politics lacked the nuance and ethical seriousness his later statements displayed. Graham learned from his mistakes—most notably after Watergate—and he recalibrated his relationship with the presidency. Graham refused many of Reagan’s requests for political favors, even though he considered the Californian the closest of his presidential friends. Graham also distanced himself from the Christian right. But because members of that movement cited Graham’s early flirtations with the White House as inspiration, Bothwell intimates that Graham was the spiritual father of the Christian right. Such a conclusion depends on a sketchy chronology and spotty causality.

It’s a shame that Bothwell’s book lacks nuance and depends on specious evidence, because it could have performed the vital service of offering an unflinching look at the harmful effects of religion in politics. Graham needs critics. His grandfatherly image and astounding record of service in ministry have caused many supporters to sanitize his career. It’s easy to forget that Graham elbowed his way into the White House and benefited as much from his interaction with U.S. presidents as they did from association with him. He was nothing if not a striver, and his ambition caused many missteps. Graham’s career offers a cautionary tale for preachers involving themselves in politics. Unfortunately, Bothwell narrows his potential audience by maligning a man whom many have fast-tracked for Protestant sainthood. Graham’s legions of devotees have legitimate reasons to celebrate him. Had Bothwell acknowledged those reasons, his critique might have caused some to investigate their hero’s mistakes. Instead, The Prince of War largely preaches to the choir of the secular left.

Graham’s legacy

Billy Graham’s close friendship with eight chief executives is unprecedented in American history. No other preacher has come close to matching that feat, and the authors of these two books offer differing appraisals of how Graham used his extraordinary access to power.

I suspect, however, that neither book will do much to change the minds of readers. Gibbs and Duffy offer a nuanced appraisal of Graham’s pastoral concerns for U.S. presidents, showing him to be a kind and faithful servant of White House occupants. Bothwell, conversely, takes aim at Graham’s war-friendly mentality and selective memory in order to expose the evangelist as a greedy power monger. Readers’ reactions to both books will probably depend largely on their previously held views of Graham.

Meanwhile, there is still much more to be said about Graham. He personified the “Southernization” of American culture during an era when the U.S. elected eight consecutive presidents from the Sun Belt. (Gerald Ford hailed from Michigan, but he was not elected to the presidency.) It’s no coincidence that Graham found much in common with these men. He shared their worldview and their religious sensibilities. Understanding Graham’s political legacy depends on a richer appraisal of the ways Southern history and culture shaped both his ministry to the presidents and his influence on American religious life, themes that forthcoming books from Steven Miller and Grant Wacker promise to cover in greater depth.

Even so, The Preacher and the Presidents and The Prince of War render a valuable service. By providing conflicting accounts of a life lived in the public eye, these two books reveal the fundamental difficulty of biography. If the authors have failed to offer perspective on every aspect of Graham’s career, they nonetheless move conversations about his legacy forward.

[Seth Dowland teaches in the Duke University Writing Program. He received his Ph.D. from Duke in American religious history earlier this year.]

The Prince of War

Author Cecil Bothwell will make upcoming appearances at the following venues to promote his new book, The Prince of War:

• Friday, Nov. 16, 1-4 p.m.: Touchstone Gallery (318 N. Main St. Hendersonville)

• Saturday, Nov. 17, 7 p.m.: Malaprop’s Bookstore (55 Haywood St., Asheville)

• Friday, Nov. 30, 7 p.m.: City Lights Book Store (3 East Jackson St., Sylva)

• Saturday, Dec. 8, 2 p.m.: The Open Book (110 S. Pleasantburg Drive, Greenville, S.C.)

I think Seth Dowland has missed the point a bit. Bothwell never professed to be offering a comprehensive narrative on Graham’s life. The thesis of the book was the inconsistencies between Graham’s public persona and his private lobbying of people in power. Graham did not merely condone or acquiesce to bellicose behaviors by various presidents, he vociferously adevocated such behaviors.

Bothwell’s book did precisely, and well, what its title promises.

“Bothwell allows Graham no room to grow and change.”

Having not read the book yet… I look forward to seeing how this plays out. Yet it is a common problem among political critics (on either left or right): their opponents are not allowed to grow, change or evolve. An opponent who was once tagged as “X” must always stay “X” in order to be evil.

Kudos for MoutainX in getting an outsider to do the review!

I would argue that I report considerable change in Graham, particularly after revelation of Nixon’s extensive taping made it clear that White House conversations were not necessarily privileged.

But, taken as a whole, the Graham who told G.H.W. Bush that Saddam was “the Antichrist itself” in the week before the Gulf War is very much the same Graham who fired a gun through a door to silence a fellow student mocking him from the other side, urged Truman into Korea, took Sen. Joe McCarthy’s side versus the U.S. Senate, urged Eisenhower to wag the dog in Cuba, bolstered Johnson and Nixon in Vietnam and told a crusade audience that Cambodia was lucky he wasn’t president when it hijacked the U.S. merchant vessel Mayaguez during Ford’s White House tenure. (“I tell you something would be done about it!”) If “terrorist” replaced “communist” in Graham’s later rhetoric it may be less a sign of personal change than of a shifting target for U.S. militarists, and he was as willing to bless President George W. Bush’s war on terror in 2001 as he was to embrace Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s intent to invade China in 1951.

I have asked Seth Dowland for references to Graham’s putative change of direction on armaments but have received no response. I have found nothing outside of Graham’s own remembrances, which have often proved unreliable. Meanwhile, the “spiritual awakening” he perceived behind the Iron Curtain is somewhat difficult to separate from the business opportunity it presented.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Dowland has contacted Xpress, saying he has not received a query from Bothwell. Bothwell says he queried Dowland via an e-mail form on Duke’s Web site — but evidently that query has not reached Dowland.

Jon Elliston

Managing Editor

Jon,

Did Dowland make any effort to reach Bothwell before he contacted you to call him a liar?

If Dowland does not check his e-mail, or the Duke Info Tech dept. is behind the curve a little – that does not make Bothwell a liar. A little checking on Dowland’s part before dragging out the heavy artillery would have been

the professional, and courteous, thing to do.

If Dowland did not first contact Bothwell, then I am left to conclude that when it comes to criticism -literary or otherwise – Dowland is less a medical examiner and more a mere bone picker.”

Dr. Manners:

No one called anyone a liar — and Dowland hardly pulled out any “heavy artillery.” Instead, he discretely contacted me, since we’ve been in touch and he had my contact info, to let me know that he hadn’t received any correspondence from Bothwell. He wasn’t trying to hurl any allegations — just to clarify that he hadn’t been contacted.

Jon Elliston

Managing Editor

No, he “discreetly” (and gratuitously) contacted you. Not “discretely.” But, hey, let’s not get petty. My keyboard makes mistakes, too.

To the extent that there is a distinction between “calling” someone a liar, and “implicitly asserting” that someone is a liar, you are correct.

The gentlemanly thing to do, however, would have been to contact Mr. Bothwell – and allow Mr. Bothwell to post a complimentary report to that effect. Short of that, he could have simply posted a response (as opposed to a reply – that may or may not have been responsive) to Mr. Bothwell’s initial query.

Going “over someone’s head” is generally recognized as having at least deployed the grenade launchers, if not actually calling up the battalion artillery officer.

Actually, he was quite discreet, and not the slightest bit gratuitous. Nor did he so much as implicitly suggest that anyone lied — he just wanted us to know he hadn’t received the query — he was clarifying circumstances and details, which we always welcome.

And I wouldn’t see it as “going over someone’s head” — when you see a mistake in a publication, you often contact the editor, as that person is often in a position to address the matter.

Thanks for you comments,

Jon Elliston

Seth Dowland and I have now made contact. He has suggested some reference sources concerning Graham and SALT and explained his reference to “specious sources.”

Both of these concerns will be addressed in the revised version of my book which will appear in book stores on the official release date, Nov. 15.

The sow who eats her young soon becomes bar-b-que. Is this the beginning of the end for Mt.X? Certainly not many of Grahams minions read the rag or patronize the mostly hip alternative businesses that are making the publisher wealthy. Time to throw the x=press in the ditch and find a new venue for Asheville cultural news. I for one plan to quiz each and every one of their advertisers why they continue to support supine sycophants who dance to the Baptist tune. Cecil lives!

Oh, please. Get a grip. Minion is a word equally applicable to those who decide to enforce a left-winged goose step.

Graham was raised a Presbyterian and currently lives at a Presbyterian College/Retreat Center. While conservative, I think “non-denominational” describes his ministry.

http://drbillygrahamministries.org/about-billy-graham.php

It is easy to assume what someone meant and I hope everyone knows how to spell ass u me.

maybe someone should as Billy Graham.

Don Yelton!

Way to get in there and defend the grammatically challenged. Just because someone doesn’t command the english language well doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try to wade through misspellings and impenetrable syntax to try to glean what they might have meant.

Hear’s tO yuo, Don? Thaks fro been a chapion ofr foks hoo dont spail so gud!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

Lemme back up to Oct. 18 – with all due respect to Gordon Smith.

1. Discrete and discreet are two, discrete words. No, they are not soft spoken, generally unnoticed or politely euphemistic. They are DISTINCT, separated in time and place (and meaning) from one another.

2. If an individual asserts that he mailed something to someone, and the someone has not made a trip to the mailbox in a few days, nor made any effort to contact the individual, but feels free to call the individual’s supervisor to state that no letter has been recieved – that is an implicit and/or irresponsible suggestion that the item had not been mailed – that the original assertion was a lie.

Regardless of the whereabouts of the “letter,” had this Dowland creature sought to resolve that issue, rather than create a different issue, the thing to do would have been to contact Bothwell. What useful information, Jon, would you possibly have had to resolve the matter of the missing missal?

Clearly, going over Bothwell’s head was an act of “dragging out the heavy artillery.” In light of recent events, perhaps I should have refered to “heavy-handed artillery,” or, more precisely, to “ham-handed artillery.”

Jon, you need to get your ego in check. Buy a dictionary that does not have cartoons in it, and concede that there are many of us out here with a greater command of English than you will never attain. Cecil could have helped you with the distinction between discrete and discreet

You might also reflecct a little on the fact that you’d never have been in a position to make the outrageous move you did last Friday were it not for the fact that Cecil relinquished that position in the first place. Had he not been more interested in writing that stuffing a shirt each morning, perhaps he’d have run your sorry backside off months or years ago.

And no, this is not Cecil writing. I am a high school classmate of Cecil’s and we have remained in touch over the years. The Winter Park High School mascot is the Wildcat – hence the initial post.

I do hold a Ph.D. in communications – hence the Dr. Grammar post, and have also served in a public affairs and protocol position in the 82d Airborne Division, and have directed the public relations, communications and protocol activities at two universities – hence the Dr. Manners post.

So let’s get this straight. Dowland owed Bothwell the professional courtesy of a direct call to say that he had not received an email that Bothwell allegedly sent?

Okay, by the same logic then, Bothwell first owed Dowland a direct phone call to ask if his email had been received before committing to print that Dowland had not responded it. Everyone knows that when a journalist prints that their attempts to contact were ignored that there’s an inference made on the part of the reader. A knowing nod. Wouldn’t the journalistic thing to do have been to verify its receipt before publicly claiming it was ignored?

Yo, Who (not to be confused with “yoo-hoo”),

Yep, you got the first part right. But after that your logic falls apart. If Bothwell’s initial attempt to contact Dowland failed, why would he think a second – or third – attempt would succeed? (See Definition of “crazy”: doing the same thing over and over, expecting different results.)

Bothwell can produce his outgoing e-mail log, if that is the means he used in his initial attempt, and easily establish the fact that the attempt had been made.

The point you seem to be striving to avoid, is that Dowland has not asserted any attempt to contact Bothwell, despite the self-evident knowledge that Bothwell asserted that he had attempted to contact him. Even if Bothwell’s assertion were not the case, or if he had a typo in the e-mail address and the message really did not reach Dowland, it still behooves Dowland to try to resolve the matter directly with Bothwell. There will be plenty of time to call him a liar, later. Having actually made some effort to establish the facts, or contact Bothwell, would have lent a great deal of credence to the slanderous assertion Dowland made, and would also have removed the cloud of suspicion surounding his motive.

Of course, all this is predicated on the putative assumption that Elliston’s recitation of events is accurate.

Was it not written that Cecil attempted an email through webpage? Oh darn. No email log. And web forms for email is are even less reliable than standard email. An email sent is not necessarily an email received, as most of us know. The professional thing for Cecil to do would have been to contact Dowland by phone (or even alternate form of mail or fax) to let him know that an attempt had been made before printing that the attempt was ignored. Had this been done, your theory might hold water. As it doesn’t appear to have been, it’s simply a double-standard.

“Was it not written”? Has not that phrase been used to foist some of the world’s most colossal, and deadly, whoppers?

Bothwell simply stated, in his original post on this thread, that he “asked” for information from Dowland. I don’t see any indication of the manner in which the request was made – phone message, e-mail, telegram, Goodyear blimp … .

Regardless – with or without a trail – courtesy dictates an attempt to resolve an issue of this sort at its source.

All that said, Dowland is obviously early in his career. I suspect he’ll do well in the years ahead. His was not a capital offense. I would not even suggest that it was malicious – just a little careless. I am sure Cecil harbors no ill will. Cecil is a forward-looking kind of guy who really and truly does hope – and work – for a world increasingly populated with “important” people – right up to the point that we eventually realize that each of us is important; even you, who.

Peace on you.

Over, and out.

Philip Breeze

Heck fire can we all love each other. NO we must label each other and avoid frontal confrontation. I just like it up front and plain spoken and do not pay much attention to people who worry about the tiny details and how the words are used. That is an indication of real intellectualism????????? come on. The real problem today is nobody really wants to discuss they just want everyone to say they love and then act like they hate.

Read Elliston’s comment above. “Bothwell says he queried Dowland via an e-mail form on Duke’s Web site”

And yes, courtesy dictates an attempt at resolution at the source, which is why Bothwell owed the guy a call before printing that he had received no response.

Plain and simple.