Photos by Max Cooper

If buildings could talk, what City Hall and the Buncombe County Courthouse had to say to each other might not be fit to print. For nearly a century, these incongruously paired architectural oddities have sat side by side in downtown Asheville, their sharply contrasting styles graphically expressing the two local governments’ often adversarial relationship. Through boom times and busts, that historic rancor has reflected a deep philosophical divide, producing such memorable donnybrooks as 2005’s water fight and long-running spats over things like county investment in the city’s core.

Tried and true: The main lobby of the Buncombe County Courthouse. The commissioners preferred architect Frank Milburn’s Neoclassical design to Douglas Ellington’s Art Deco innovations.

Buildings are, of course, mute, but that was hardly the case for the pair of stubborn men perhaps most responsible for those mismatched landmarks. In the 1920s, Asheville Mayor John Cathey and Chairman Edgar M. Lyda of the Buncombe County Board of Commissioners directed a steady stream of invective back and forth, and the legacy of that feud has tainted city/county relations ever since.

For his part, Cathey publicly blasted a Chamber of Commerce committee that stood in the way of his plans for a new city building, calling them “kickers and soreheads” and, for good measure, “a bunch of jackasses.” “That city hall,” he told the Asheville Citizen in 1926, “is going up if we have to lay the foundations so deep they will hinge on hell!” A more taciturn but equally determined Lyda, meanwhile, gave as good as he got.

And as these seats of local government gear up for their 85th anniversaries, both are undergoing extensive renovations that, once again, mirror underlying attitudes. This time, however, the two sides are aligned.

After separately considering forsaking their respective downtown headquarters in favor of more modern suburban complexes (see sidebar, “A Hole in Downtown”), city and county leaders are now cooperating closely on the renovations. They’re united by a shared sense of history, a commitment to downtown — and a determination not to repeat the mistakes of the past.

When those structures were built, “There was a real missed opportunity, and we’re not going to do that again,” vows David Gantt, chair of the Buncombe County Board of Commissioners.

Grand plans

The 1920s were an extraordinary time in Asheville. In just two decades, a sleepy mountain town doubled its population, morphing into a growing metropolitan center. The Jackson Building downtown was Western North Carolina’s first skyscraper, and other new, state-of-the-art structures were rising all the time. Building permits brought in $4.2 million in 1924 alone, numerous sources report — an astronomical sum for the time.

Both the courthouse and City Hall were too small to accommodate that growth, and John Nolen’s 1922 “Asheville City Plan” had envisioned a suitably impressive “civic center” (today’s City/County Plaza) featuring matching, linked government buildings, a park and even a bus station. Several prominent civic leaders endorsed the idea, deeming the existing facilities insufficiently grand as emblems of enhanced civic pride.

The city hired architect Douglas Ellington to design the twin structures, and a determined Mayor Cathey was eager to start construction of the City Building. “I intend to see it go up if I lose every friend I have in the city and forfeit forever the chance of making any more!” he declared.

The Chamber committee, which basically supported the plan, was urging Cathey to hold off until the county agreed to build a similar-looking structure. Undeterred, Cathey dug in his heels, saying, “I simply refuse to be bullied off a thing that is for the best interests of the city.”

But Lyda and his fellow commissioners had doubts about the thoroughly modern style — and about Ellington himself.

“The county thought the Art Deco design was too radical. No one had ever seen that stuff before,” local historian Jim Coman explains. “It was just totally off the wall: To them, it was like bringing in Salvador Dali. The county commissioners were more conservative; they always have been.”

Fifty years later, an unnamed observer of the era’s politics would tell the Asheville Citizen-Times that “The two men didn’t exactly constitute a mutual admiration society.” Instead, they embodied “the natural rivalry between city and county government.” It was an understatement.

Once upon a time: Stacy Merten, the city’s director of historic resources, displays the 1928 announcement of City Hall’s dedication ceremony, one of the first events in the region to be broadcast on the radio.

In the end, the county went with Frank Milburn, a respected Washington, D.C., architect famed for his work on grand public buildings throughout the Southeast. He was chosen, noted Lyda, for his “nationwide reputation and thorough experience.” The 17-story courthouse, Milburn’s final project, was the tallest local-government building in the state when it was completed, two years after the architect’s death.

“Ellington woke up and found out from the newspaper that his plan had been rejected,” says Stacy Merten, the city’s historic resources director. “It was a bit of a shock: They hadn’t told him.”

Conflicting visions

All thoughts of a unified approach abandoned, each government now went ahead with its separate plan. A breathless account in the Asheville Citizen praised Asheville’s City Hall as representing “the new school of modern buildings which are in vogue in larger cities of the country.”

Later that year, the same newspaper hailed the courthouse as a monument to “paternal pride.” It was hardly spartan, however. The county, notes Coman, employed two people just to polish the brass, and all the furniture was made of black walnut.

The cultural divide extended even to the art on the walls. Five murals by New York artist Clifford Addams adorn the City Council chamber. Their “freedom of style,” a 1928 Citizen review observed, was “as much of an innovation in Asheville as the city hall was a departure architecturally.”

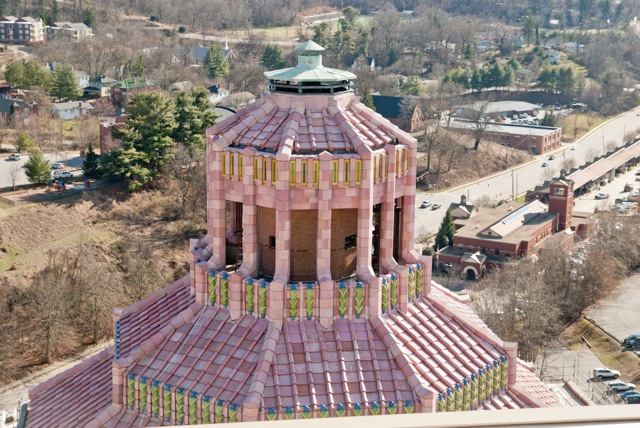

Enduring symbols: The iconic dome of Asheville’s City Hall, viewed from the Buncombe County Courthouse roof. Both historic structures are undergoing major renovations to prepare them for further decades of productive use.

The county courthouse, on the other hand, is filled with staid, formal portraits of judges and civic leaders. “The cutting-edge and the tried-and-true,” is how Coman characterizes the contrast.

“I’ve heard it described many times as a gem of a city hall beside the box it came out of,” says longtime City Council member Jan Davis with a laugh. As a young man, he worked in a nearby garage.

A question of honor

City Hall warrior: A Spanish-American War vet with a fiery temper, Asheville Mayor John Cathey (1923-27) pushed many grand civic projects. He clashed bitterly with the county and Chamber of Commerce over the City Building’s design.

One thing Cathey and Lyda apparently did agree on was that the current deluge of tourists and cash was the answer to the area’s long history of scarcity. Both men’s comments to newspapers at the time reflect a shared belief in unimpeded progress.

But the two disputed buildings had barely been completed when the stock market crashed on Oct. 29, 1929. The boom, heavily financed by both public and private debt, was over. Asheville’s Central Bank and Trust Co., with assets of $52 million, went bust the following year, and many other local banks soon followed. Three out of four county employees lost their jobs; Cathey’s successor, Mayor Gallatin Roberts, committed suicide in an office above the bank.

Municipalities across the country simply declared bankruptcy, but Asheville and Buncombe County were determined to honor their debts. Setting aside their considerable differences, the two local governments managed enough cooperation to consolidate their debt in 1936, launching a dogged, four-decade campaign to pay it off.

“This was a very Scotch-Irish society: They said, ‘No, we’re not going to default,’” Coman explains.

That, however, left both governments critically strapped for cash, and as the area’s fortunes waned, so did the state of its civic landmarks. Throughout the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s, newspaper reports document the two buildings’ deterioration. There were multiple health and safety violations, particularly in the courthouse, but little money to fix them. Whole floors were vacated, and the occasional renovation efforts of more recent decades were limited in scope. Even the chimes that once rang out atop City Hall fell silent; they wouldn’t be heard again until 1998.

Mending fences

Back in business: The courthouse renovation is converting long-unused floors into office space. In the decades after the Great Depression, up to 60 percent of City Hall was vacant; the top floors of the courthouse were an unsafe jail.

As recently as seven years ago, the two local governments were duking it out over the fate of the city’s water system, a prolonged and bitter battle that eventually included both the courts and state legislators. During one acrimonious negotiation session, Commissioner Bill Stanley declared, “You can’t trust the city of Asheville.”

Since 2005, however, the rancor has slowly dissipated, various elected officials maintain, with quiet fence-mending replacing public squabbling.

“Obviously, we hear so much about the water system, but frankly relationships today are better than they’ve been in a long time,” says Davis. “Naturally, cities and counties have different functions: They don’t agree on everything. There has been a divide over the years, but the reality is, both levels of local government are very important.”

Gantt agrees, crediting improved communication with laying some of the problems to rest. “I think there’s the best relations between the county and the city in a generation,” he proclaims. “There’s a lot of cooperation. We’re more concerned about the state and what it’s doing to the city and county. Even with the new board [of commissioners], I don’t really hear the acrimony that was there before.”

And Stanley, who recently stepped down after 24 years on the Board of Commissioners, even vouched for the city’s trustworthiness at a Dec. 12 meeting of the Metropolitan Sewerage District board, defending city government against a state proposal to seize the water system.

Over the last seven years, the city and county have cooperated on greenways, consolidating their 911 systems, planning for emergencies and even renovating the Civic Center — which would have seemed an improbable dream in the contentious atmosphere of 2005.

But Coman, retired now after 30 years on the county payroll, wonders how long this era of good feelings will last. “That difference has endured since the city and county first existed,” he points out. “And I imagine it will continue for a long, long time.”

Indeed, recent referendum votes on issues ranging from Amendment One to the A-B Tech sales tax show city and county voters still sharply divided. And when, in 2011, the General Assembly abruptly mandated district elections for the county commissioners, supporters of the move (many of whom lived outside the city) said it was needed to give outlying areas better representation. Some city residents, meanwhile, criticized the switch as undemocratic. It remains to be seen how the resulting, politically divided Board of Commissioners will operate.

Still, Gantt says that during the current renovations, he’s made a conscious effort to avoid the kind of fighting that attended the two landmarks’ construction.

“Today, the county wants to support the city and respect what has happened,” he explains. “We’re going to have an 85-year-old building that will be good for another 75 to 100 years. We thought that with the history and the connection with the city, we couldn’t rip that out.”

Abiding faith

On March 18, 1928, thousands attended the dedication of the City Hall that Cathey and others had fought for so vigorously — one of the first public events in the region featuring a live radio broadcast.

A grand design: Asheville City Council member Jan Davis, who worked in a nearby garage in his youth, poses in front of the City Seal. Even in tight budget times, he says, renovating City Hall shows a commitment to Asheville’s roots.

No longer mayor by that time, Cathey nonetheless rose to speak about the city’s progress, noting that his pastor, perhaps mindful of the politician’s notorious vitriolic rants, had commanded him not to curse. And for once, contemporary accounts confirm, Cathey held his temper.

Later that year, on Dec. 1, county residents “came from the farthest rural coves,” the Asheville Citizen reported, to witness the opening of their new courthouse. Lyda, too, was on his way out of power by then, and after having fiercely resisted the city’s zeal for modernity, he now struck a conciliatory note. The massive new structure looming behind him, he said, was for future generations of both city and county residents.

“We have an abiding faith in the future and believe that it is not a far cry to the time when Buncombe County will be a veritable city, and Asheville will be Buncombe County,” Lyda declared. “Asheville is not localized. Its fame is as universal and far-reaching as the rising and the setting sun.”

Fifty years later, an anonymous resident who remembered the Cathey/Lyda fight was quoted in the Asheville Citizen-Times. Speaking with the benefit of hindsight, he observed: “It is pointless to try to say now … that one was right and the other was wrong. They simply did what they thought they had to do.”

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.