Editor’s note: In “If the Creek Don’t Rise,” (May 27 Xpress) we considered the history of flooding in the River Arts District, current city redevelopment projects there, and concerns raised by members of the RAD community.

In part 2 of this story, we delve into the French Broad watershed’s physical characteristics, how perceptions and use of the river have changed, and the nuts and bolts of development in a flood hazard area.

The French Broad River gets its start near the little village of Rosman in south-central Transylvania County. Spilling down the western slopes of the Eastern Continental Divide, the river flows north for 117 miles through Henderson, Buncombe and Madison counties before crossing into Tennessee.

Many tributaries feed the French Broad: The Davidson River comes in near the Pisgah Forest community outside Brevard, and the Swannanoa, flowing west from the North Fork and Bee Tree reservoirs in eastern Buncombe County, joins the French Broad near Biltmore Estate. There are also many smaller streams that feed into the French Broad as it makes its way to Asheville.

In her landmark 1955 book, The French Broad, Asheville author Wilma Dykeman said the river was “above all, a region of life, with all the richness and paradox of life.” She described a watershed rich in flora and fauna, ranging from the “fertile fields and gentle fall” through Transylvania and Henderson counties to the sudden “plunge between steep mountains” around Asheville, “strewn with jagged boulders.”

In the course of that journey, the French Broad traverses landscapes ranging from protected forestlands to more urban environments, providing habitat for over 44 rare or endangered species, including the mountain sweet pitcher plant and the Appalachian elktoe mussel.

Yet throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the French Broad also played a central economic role: The timber and textile industries used the river as an access point to move materials through the region.

“Asheville’s history is tied to the river,” says Stephanie Monson Dahl, director of Asheville’s Riverfront Redevelopment Office. She also mentions the railroad depot’s close proximity to the river as a major reason businesses historically located there.

By the early 20th century, however, deforestation of surrounding land led to the loss of what Dykeman called the French Broad’s “natural sponge.” In the catastrophic flood of 1916, timber and manufacturing byproducts piled up around bridges and natural barriers, compounding the effect of the rising waters by restricting the river’s flow.

“We were a huge logging industry,” says Monson Dahl. “What you see today is really a different river than it was back then.”

An evolving vision

John Nolen’s groundbreaking 1922 Asheville City Plan called for flanking the French Broad and Swannanoa with parkland, which would also reduce flood risks.

The closing of the train station on Depot Street in 1968 meant fewer people coming to the area. The 1978 launch of the Land of Sky Regional Council’s French Broad River Improvement Program, the 1983 founding of the French Broad River Foundation (which eventually merged with RiverLink), and other milestones helped expand the focus. Rather than simply cleaning up the river, the goal became transforming a failed industrial corridor into a viable part of the city and a tourist attraction.

In 2000, Asheville’s Sustainable Economic Development Strategic Plan listed riverfront revitalization as one of the city’s four top priorities, calling the area “an asset for both enhancing quality of life and attracting economic activity.”

“This was the first time you see the plans for the river include transportation, economic development, housing and integration of a more sustainable model of development,” notes Monson Dahl. It also marked the start of Asheville’s “land banking” process: acquiring reclaimable riverfront property for future rehabilitation and development.

City planners now say the RAD could become the center of a citywide transportation network connecting downtown and the river with other parts of Asheville via a series of greenways and improved pedestrian infrastructure.

“People want to walk; they want greenways and better access,” says Monson Dahl. “We’re creating a hub for a real greenway network, where people can go from destination to destination or do a loop walk. Right now, Asheville doesn’t have that.”

These ambitious plans have seen private investors come calling about development opportunities in the district. In 2012, New Belgium Brewing Co. bought the former Western Carolina Livestock Market site on Craven Street; the brewery’s East Coast production and distribution facility is now under construction there.

“We recognize that private investors have chosen to invest in the River Arts District,” says Monson Dahl, adding that the public sector’s responsibility is “creating an environment that’s safe and clean, and ensuring that any development that happens is done in a way where it provides no impact to the rest of the area.”

Last year, the city secured a $14.6 million TIGER grant from the U.S. Department of Transportation to fund intersection improvements, bike and pedestrian paths, and greenways in the area.

Construction cookbook

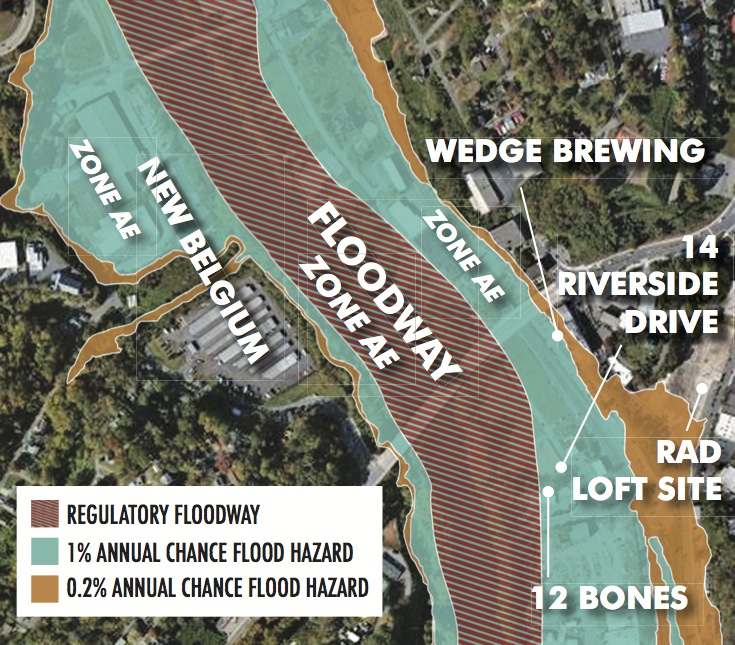

The first step in any new development in the district is meeting federal, state and city floodwater management guidelines. The Federal Emergency Management Agency has designated 74 percent of the RAD a “special flood hazard area”; 27 percent of that sits in the floodway and can’t be developed, except for things like transportation and parks that won’t significantly affect water levels. The remainder, labeled Zone AE, can be developed but is subject to various levels of restrictions, depending on the specific site and building characteristics and other factors (see map). There are also some outlying areas with lower flood risk.

According to the interactive flood maps found on FEMA’s website, Zone AE includes portions of Lyman Street, Riverside Drive and recreational facilities such as Carrier and French Broad River parks. The area immediately outside the floodway is home to such businesses as 12 Bones Smokehouse, Gennett Lumber Co., Asheville Waste Paper and the New Belgium site. At the city’s request, notes Monson Dahl, FEMA is updating those maps, which were done in 2010. Any subsequent development will affect the new versions, which are due out around 2020.

Federal guidelines for construction in such flood hazard zones include standards for the type of fill supporting foundation structures, the composition and elevation of foundations, building materials’ flood-resistance capability, and design features integrated into a structure to minimize flood impacts, as detailed in a manual produced by the American Society of Civil Engineers. There are also state requirements which, in North Carolina, include building at or above the specific area’s “base flood elevation” — the level that floodwaters have a 1 percent chance of reaching or exceeding in any given year. Any parts of a structure below that threshold must be designed to mitigate flood impacts. The state website ncfloodmaps.com provides comprehensive guidelines for the permitting process and spells out requirements for new and existing structures.

To do a construction project in the RAD flood zone, Monson Dahl explains, “You have to get a certificate that you’ve created no rise in floodwaters and go through a large permitting process that includes a flood impact study.” If the study finds that the project could cause flood levels to rise, steps must be taken to mitigate that impact, either by creating stormwater retention areas on adjacent properties or moving the project elsewhere.

Asheville, meanwhile, has “extra requirements on top of state regulations for flood plain construction,” she says. They include setting the construction threshold 2 feet above the state’s base flood elevation requirement.

Harry Pilos, who’s developing the RAD Lofts on the former Dave Steel property, says “When you get rid of dirt and replace it with concrete, it’s going to have a negative impact.” The broader debate, he continues, “is how much commercial development will go into an area that has right of way issues with Norfolk Southern, that is in a flood plain that we all know floods, and then there’s substantial environmental issues from the fact that it was an industrial corridor next to a railroad track for over 100 years.”

Creative approaches

All those rules may sound daunting, but Monson Dahl cites several local developments that have found creative ways to work with the requirements. The office/retail project at 10 Brook St. in Biltmore Village, for example, built a ground floor parking area that doubles as a “flow-way” under flood conditions. And the flood-proof design of the Smoky Mountain Adventure Center, now under construction on Amboy Road, calls for using the rear portion of its extended foundation as a climbing wall.

Other developers simply choose to take government agencies’ advice and build in less vulnerable areas. “Our site is out of [Zone AE],” notes Pilos, adding that otherwise, he wouldn’t have proceeded with his project.

As for New Belgium, whose project is part of the reason for city infrastructure initiatives such as the Craven Street Improvement Project, Susanne Hackett, the company’s media relations specialist, says measures were taken to bring the facility well above the base flood elevation.

“Reusing crushed concrete from the existing site for fill, as well as bringing in additional dirt, we raised our Craven Street site out of the flood plain by up to 10 feet in some places,” she explains, adding that the entire facility is at least 2 feet above the flood requirement for the property.

Hedging bets

One key lesson some local business owners learned the hard way in the devastating 2004 floods triggered by hurricanes Frances and Ivan was the need for insurance coverage. The National Flood Insurance Program, notes FEMA’s website, provides “access to affordable, federally backed flood insurance” that wouldn’t otherwise be available, and the agency’s flood maps help insurance companies set the premiums for that coverage.

“Payments [for claims] are backed up and supported by the federal government because no private insurance company will offer to write flood insurance,” explains David Mann, vice president of Webb Insurance in Asheville. “The peril is deemed too catastrophic and would bankrupt the insurance mechanism. The only body willing to take on that kind of financial exposure is the federal government.”

Various factors are considered when calculating insurance rates in a special flood hazard area, including the flood zone, location, building age, occupancy, foundation type and building elevation in relation to the base flood elevation. Federal guidelines provide insurance cost estimates for both residential and commercial developments.

That cost, says Mann, is “not outrageous, but it’s not cheap either.” For a typical commercial building in the RAD flood zone, the maximum available coverage might run $3,000 to $4,000 annually, depending on the limits. “If you’ve got a million-dollar building, the maximum that you can buy is $500,000. If you think a flood will completely destroy the building, you’re still only going to get half of that back. Like most insurance, you have to weigh the risk versus the cost. Are you willing to absorb some of that cost in case of a catastrophe?”

But by tightening the requirements for building in the flood zone, notes Monson Dahl, Asheville helps investors qualify for lower rates. Thanks to the city’s participation in the federal Community Rating System program, she explains, developers in the RAD may qualify for a 10 percent lower insurance rate than those building on comparable sites in other parts of the state.

Left in the wake?

Amid all the excitement about the River Arts District’s current boom, however, there’s a downside for low-income residents and renters.

“A recent study funded by the city, ‘Alternatives to Gentrification,” already revealed that the RAD area is in the ‘middle stage’ of gentrification,” Mari Peterson wrote in an April 15 article on the watchdog site Asheville River Gate. And by hiring the Austin, Texas-based consultant Code Studio to create form-based code zoning in the RAD, she maintains, the city is laying the groundwork for rapid investment in the area that will drive up property values and rents — and ultimately drive out many artists and other residents.

“In many ways,” argues Peterson, form-based code zoning “transfers development power from the developers to the city, because they can dictate everything from use of space to materials and design. It essentially dictates development standards based on the whims of the City Council at that time, rather than really thinking about growth for the long term.”

Metal artist Jeri Bartley lives and works in the district. “I bought my house five years ago, and was able to afford it largely because it’s in the RAD,” she explains, noting that there have been problems with vandalism and squatters. “I had a cash offer on my house that was more than I’ve ever been able to afford in another house. I considered it but realized I wouldn’t have a place to live, because even with that amount, you can’t buy a house in downtown or the RAD now.”

As for the future, Bartley says “Maybe I won’t be able to afford it in the future, but … if I ride the wave right, then I don’t think I’ll be priced out. My work will sell more, and there’ll be people coming into the RAD who can afford to buy it.”

Monson Dahl, meanwhile, acknowledges that certain individuals and neighborhoods may be negatively affected by new development, but she assures those living and working in and around the RAD that the city is also trying to accommodate their needs.

“Just like downtown, we know that surrounding neighborhoods are going to feel the impacts of the revitalization,” she says, noting that the 2014 “Alternatives to Gentrification” report was “the first time we surveyed artists in the RAD to ask them how much they pay, if they’re afraid of losing those spaces, and how we can help.”

Monson Dahl also mentions the city’s Equitable Development Strategies initiative, which will include a two-day workshop with community leaders and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to consider how residents of surrounding neighborhoods can benefit from the changes taking place in the district. Meanwhile, the Livingston Complete Streets Project will focus on expanding infrastructure from Depot Street through Livingston Street to Victoria Road. Both projects are slated to begin later this year.

But Monson Dahl also emphasizes the importance of ongoing communication with residents.

“We do a lot of outreach, but it’s obviously not reaching everyone,” she concedes, encouraging concerned community members to contact her personally with questions or attend one of the open public meetings of the Asheville Area Riverfront Redevelopment Commission, held the second Thursday of each month at City Hall. Monson Dahl has open office hours the third Thursday of the month.

“I care a lot about the success of this project, and I want people to know that they can call me at any time,” she says. “We want to find out what parts of the project people are interested in, and provide information quickly and efficiently. We want do it the right way.”

It’s rather telling about this community’s attitude towards the French Broad. No mention of the cost the river suffers when humans build where they ought not. No mention of who will be responsible for the tons of trash and chemicals sent floating downstream. Since it was mentioned that ‘history repeated itself…” when refering to recent floods that where much less than half of the actual highest recorded flow I would guess(given my knowledge of events of the recent past) this imaginary number is where the permitting would begin. Pretty smart as the real number would greatly limit what could be built and then when all that is inundated they can simply shrug their shoulders and say “Well who knew?”.