Jane moved into the Deaverview Apartments, one of Asheville’s 10 low-income housing communities, in September 2017. And from the very beginning, she says, she often feared for her life.

“It was a nightmare. If you want to talk about terrifying, I lived there alone,” says Jane, who asked Xpress to use a pseudonym because she feared retaliation. She now lives with her boyfriend and family in South Carolina.

During her 14 months at Deaverview, Jane says she heard gunshots on a regular basis and frequently witnessed drug dealing in the streets. But her fear of crossing the wrong person and becoming a victim herself kept her from speaking up to management or the police.

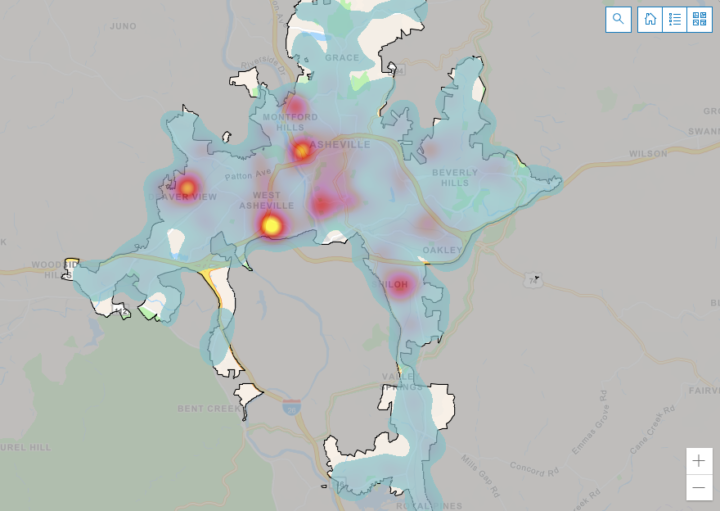

The data seems to back her up: As of Oct. 5, the Asheville Police Department had logged 425 “gun calls” in 2021, meaning incidents in which guns were fired or calls for help involving gunshot wounds. Of those calls, 130 — more than 30% — came from inside or within 500 feet of a public housing community. Last year’s data on gun calls tracked about the same, according to an APD spokesperson.

Although only 3.4% of Asheville’s population lives in public housing, roughly 16% of the most violent offenses committed within the city limits since January — including homicide, rape, robbery and aggravated assault — played out in those complexes, the APD reports.

They’ve also been the location of some of Asheville’s highest-profile murders, including the killing of 24-year-old Tiyquasha Simuel, a pregnant woman who was shot to death at Deaverview in June 2019 after testifying in a murder trial, and 12-year-old Derrick Lee Jr., who was shot and killed in July 2018 at the Lee Walker Heights apartments.

The United States Housing Act of 1937 established a federal commitment to provide “decent, safe and sanitary dwellings for families of low income.” As part of this responsibility, the Asheville Housing Authority is charged with maintaining secure and livable public housing communities. But is the authority doing enough to protect residents against gun violence and other crimes? Could redeveloping other local housing complexes along the lines of what’s currently being done at Lee Walker Heights make these residents safer?

Privilege and power

There are many complicated reasons why gun violence and other crimes tend to center on public housing communities, says APD Capt. Mike Lamb, an Asheville native who’s worked in and around the city’s public housing for 24 years. Poverty is the biggest underlying issue, he says. The Housing Authority serves people earning up to 50% of the area median income ($26,300 for a single person; $37,550 for a family of four).

Another key problem, notes Lamb, is the lack of social cohesion — “that sense of community and having a relationship with folks.” Lamb says that the issue seems to be a trend citywide. “People don’t know their neighbors as well as they used to,” he maintains. When residents have a shared sense of connection, “If you have an issue or confrontation or even just a disagreement, there’s more problem-solving efforts there and more of a willingness to talk out any problems.”

David Nash, the Housing Authority’s executive director, cites an even deeper issue: the fact that people in low-income communities lack the privilege and political power that other residents have.

“I think it’s because our entire city and our entire society allows [crime] to happen there and doesn’t allow it to happen in other parts of the city,” he explains. “The activity goes where it can go, which is to a place where people complain less about it, or where their complaints have less impact because they’re not as well connected.”

Both Nash and Lamb say that much of the crime that happens within public housing communities is committed by people who don’t actually live there. Residents charged with drug crimes or violence, notes Nash, are evicted.

The Deaverview code

One step the Housing Authority has taken to reduce crime is increasing the police presence within these communities. Since 2012, the agency has maintained a contract with the APD that pays for eight officers and one sergeant to practice community policing throughout these developments, in addition to the regular police patrols. This involves creating more positive relationships with residents and attempting to address the specific problems they face. But due to APD staffing issues over the last year and a half, says Nash, that team currently has only three or four officers.

And in any case, public housing residents are often hesitant to work with the police when violence or other criminal activity occurs. Jane, the former Deaverview resident, says that she and some of her neighbors feared retaliation by the perpetrators if they reported incidents of crime or threatening behavior.

“There’s a code in Deaverview Apartments,” she says. “As a tenant, it is a community violation to call the police.” Instead, the way to cope with crime and safety issues is “we handle our own.”

Those fears are not unfounded, Lamb concedes. Under state law, prosecutors must make available to defendants all files pertaining to the case, he explains. That means the accused can see the names of whoever provided information to police or came forward as witnesses during investigations.

“Let’s say, for example, you have somebody who’s committed a homicide and we do our investigation. We get statements from witnesses and then we put down the name of the individual who gave us the statement and attach it to the case file, so that the courts can subpoena that person as a witness to the shooting or homicide investigation. When the defense attorney gets it, the defendant also gets the same information.”

In some instances, he says, files that included the names of witnesses were shared on social media, which can “signal to the community that this person is a snitch. And we’ve seen violence and retaliation against people for cooperating with an investigation or putting their name out there to be a witness.”

To combat that and encourage residents to come forward with information, notes Lamb, the APD established an anonymous tip line that enables people to report crimes or share information without risking exposure. He says the tip line has been successful in assisting investigations while protecting residents’ privacy.

“We’ve solved a lot of crimes using that tip line, and it is completely anonymous. We can talk back and forth with the tipster but we never know who they are unless they choose to disclose their information,” he reports.

A fresh start

But increased policing may not be the only solution to rising crime rates. An Oct. 8 op-ed in The New York Times by Eugenia C. South, an assistant professor of emergency medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, reported the positive impact of interventions such as cleaning up trash, planting trees and repairing substandard properties. Two large-scale studies she and colleagues conducted in randomly selected Philadelphia communities found that crime fell up to 29% in neighborhoods adjacent to vacant lots that were cleaned up, enhanced and maintained.

In Asheville, the Housing Authority is trying out a more ambitious version of the same idea.

Just south of downtown, the renamed Maple Crest Apartments at Lee Walker Heights completed the final stages of a major redevelopment Nov. 17. Asheville’s oldest public housing development, Lee Walker Heights was built in 1950 and originally included 96 units on 12.5 acres.

“It was a bunch of poor families here. We all grew up as one big family. We all had our doors open — never closed our doors all over the hill,” remembers longtime resident Henry Butch. “And though we grew up poor, we grew up very happy.”

Over the years, however, residents increasingly lost that sense of safety. By 2012, he recalls, shootings and other criminal activity had become endemic at Lee Walker. “It was out of control. I was shocked at how bad it was.”

But sitting inside his newly remodeled one-bedroom apartment, which features high ceilings, views of downtown Asheville, an oversized bathroom and even central air conditioning — a first for the city’s public housing complexes — Butch says there’s a renewed feeling of safety and calm. “It’s a lot different than the old Lee Walker Heights.”

The approximately $37 million remodel, which began in 2017, is now about two-thirds occupied by new and returning residents, notes Nash, and it will continue to fill up by year’s end. New security lighting and cameras are much in evidence. Maple Crest will also offer roughly 212 apartments at market-rate to create a mixed-income community.

It’s too soon to know whether the redevelopment will reduce crime in the area, says Nash, but the renovations were much needed in any case. “It’s been a heavy lift for us and for everybody involved, but I think that everybody deserves a nice place to live.”

The bigger picture

With the Lee Walker Heights remodel reaching completion, Nash says the Housing Authority is now setting its sights on the Deaverview Apartments, whose 160 units are home to about 300 residents. Built in 1971 and renovated in 1996, it’s the city’s second-oldest public housing community.

In April, City Council unanimously approved spending $1.6 million to buy a 21-acre property at 65 Ford St. that could pave the way for a future redevelopment and expansion of Deaverview. One potential plan would follow the Purpose Built Communities model, a holistic approach to neighborhood revitalization that emphasizes health and wellness, education and mixed-income housing.

Eytan Davidson, vice president of communications at Purpose Built Communities, says that public safety has been one of the more visible areas of improvement in the 28 such efforts that are part of the Atlanta-based nonprofit’s nationwide network. The link between crime and public housing, he says, stems from a lack of economic opportunity as well as structural racism dating back to slavery. “If we want to get to the root of poverty in the United States, we really need to look at neighborhoods,” Davidson explains. “We believe that the neighborhood is the unit of change and that improving the environment changes people’s behavior.”

He points to Atlanta’s notorious East Lake Meadows public housing community. At one point, the 650-unit development became known as “Little Vietnam”: “The crime rate was 18 times the national average,” Davidson reports. But after introducing mixed-income housing and new schools and restoring two historic golf courses that have become sustaining economic anchors, the neighborhood has been transformed, he says.

Today, crime in East Lake has fallen by 73% and is below the citywide average. Violent crime has dropped by 90%.

The same thing happened at the St. Bernard Projects in New Orleans. In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, the complex was demolished and replaced by Columbia Parc, a mixed-income community with a school, fitness facilities, playgrounds, a clinic, a grocery store and other amenities. Here, too, crime dropped dramatically, from several hundred felonies and over 40 homicides in the five years prior to Katrina to just two attempted felonies and no homicides in the project’s first three years, according to the Build Healthy Places Network, a national nonprofit that works to improve health and well-being in low-income communities.

Reimagining Deaverview

The proposed Deaverview remake would include such amenities as a child care center, a school and a community center providing on-site health services. It would also double the number of housing units, bringing the total to roughly 300, including new housing for current residents.

Nash says the Housing Authority has begun holding meetings with residents concerning the potential redevelopment and has selected a co-developer and a design team. But Paul D’Angelo, Asheville’s community development program director, says that while Deaverview is listed as a potential redevelopment site, the city has not yet committed to the project.

“‘Purpose Built Communities’ has been discussed as a model at Deaverview, but again, no agreements have been made and no further comment from the city at this time,” D’Angelo wrote in an Oct. 1 email to Xpress.

Despite the uncertainty, however, Nash takes a positive approach. “The Housing Authority at least is going to do something at Deaverview, whether it’s a full-blown Purpose Built Community in collaboration with the city or more of a Maple Crest/Lee Walker Heights model on the property that we own,” he explains. “It’s an exciting model and I think it’s something that we’re interested in, but we’re still trying to work out the details of how to plan for it with the city, if that’s the direction the city wants to go.”

In the meantime, Nash stresses that he and other Housing Authority staff, including the on-site managers, are available to help residents dealing with crime and safety issues.

“I would be glad to talk with anybody who has a concern and try to figure out a strategy with them and APD to address that concern,” he says. “We definitely want to help try to find a solution in a confidential way, if that’s what they prefer.”

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.