Sarah Sanders stands in her driveway, outside the remodeled 19th -century log cabin where she lives with her partner, Allison, and Allison’s two children. The home sits just off the Leicester Highway in Sandy Mush, an unincorporated swath of hills, fields and forests straddling Buncombe and Madison counties. Across the road, a cylindrical white-and-orange post with a domed top indicates that a broadband (high-speed) Internet line is buried underneath. But that line doesn’t service her home or those of most of her neighbors.

“Did you see it when you came in?” asks Sanders. “It’s like it’s just sitting there, mocking us.”

Like 40 percent of rural U.S. households, Sanders can’t get service that meets the Federal Communications Commission’s current definition of broadband. In January, the FCC jacked up its minimum standards from 4 megabits per second to 25 Mbps for downloads, and from 1 Mbps to 3 for uploads.

The line that runs by Sanders’ house, which offers top speeds at least closer to those new standards, serves Whisper Mountain, a gated, green-built community set amid hundreds of acres of forest. But for complex technical and economic reasons, compounded by a grab bag of often conflicting government programs and nonprofit initiatives, Sanders and her neighbors can’t plug in.

They do have options for Internet service. HughesNet, a satellite service, provides download speeds of up to 15 Mbps, but it can be expensive and unreliable, says customer Jim Metzger. There’s also dial-up service via land-based telephone lines, at less than 1 Mbps, and wireless options such as Internet via cellphone services, which residents say are essentially unworkable, in practice.

The French Broad Electric Membership Corp. offers speeds up to 3 Mbps via a delivery system called Broadband over Power Lines, which many had hoped would help span what’s been called the “last mile” in bringing the 21st century to rural Americans’ doorsteps. But French Broad Electric — a cooperative that serves as the local power company for some 38,000 residents of Buncombe, Madison, Mitchell and Yancey counties in North Carolina, plus some in east Tennessee — can no longer get the parts needed to maintain its BPL service, which will shut down in June. The only other choice is to drive to the Leicester branch library, which is served by a high-speed line on the state-sponsored North Carolina Research & Education Network.

Meanwhile, across much of the industrialized world, fiber-optic lines deliver speeds of 100 Mbps or more. As of February 2013, though, a mere 20 percent of U.S. households — mainly in areas served by Google, large urban areas or municipalities that have their own network — could access fiber-optic-based Internet, compared with 86 percent of people in Japan and 66 percent of South Koreans. Copper lines can approach fiber-optic speeds but have limited capacity for expanding service.

And in an age when Internet access is as embedded in our everyday lives as running water and electricity, not having it is “a huge disadvantage,” says Sandy Mush resident Susan Merrill.

Parts of the problem

Ironically, the rapid pace of technological change also contributes to the problem: The FCC’s revised standards meant that, overnight, far fewer rural households had access to what was now considered broadband. Meanwhile, federally funded programs to expand that access have spent millions on technology that’s already obsolete.

In 2010, for example, French Broad Electric leveraged more than $1.7 million in federal funds and “invested in the BPL technology … to provide high-speed Internet service to a few of our members who had no other service,” says General Manager Jeff Loven. “It was the only technology available at that time that could provide adequate speed at a reasonable cost.”

BPL piggybacks data transmission over existing power lines, but the speed is limited, and there are problems with connection quality. Theoretically, the download speed was close to the FCC’s minimum standard back then, though Metzger says, “I never once connected at [3 Mbps].” He’d switched to BPL after having problems with HughesNet, but when efforts to improve his connection failed, he went back to the satellite service, which he says is faster if often less reliable.

And Jess Mund, a Sandy Mush resident who still has BPL, says it’s “usually not fast enough to stream a video. Sometimes if nobody else is online you can, but if you have multiple users online, there’s no way.”

“The technology was far from perfect,” acknowledges Loven. “It was very susceptible to ‘noise’ [on the lines] and required our crews to change insulators and transformers in several areas. There were times when the signal would degrade and service was slow.”

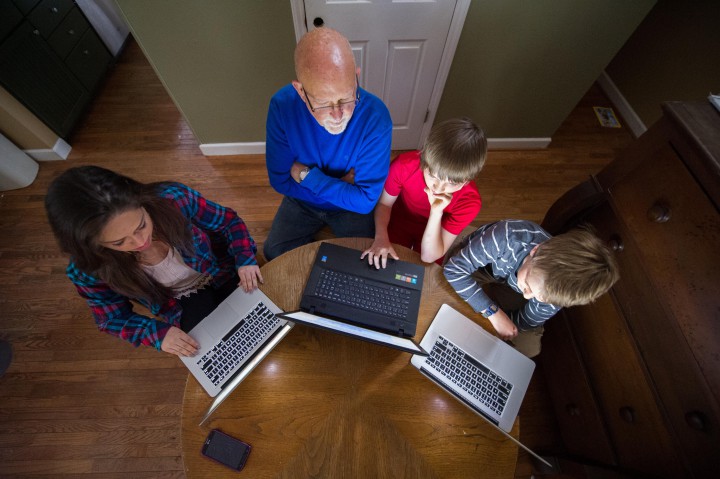

Still, says Merrill, “BPL was a vast improvement.” Before that, she explains, “We just had dial-up, and it was horrible. … We were going back and forth to the library so the kids could do their schoolwork.”

If BPL had caught on in the U.S., technological improvements might have followed, but that didn’t happen. After the last remaining U.S. hardware supplier went under in 2012, French Broad Electric bought up much of the defunct company’s surplus stock, but the service’s days were clearly numbered.

When Mund and her family moved to Sandy Mush in February 2014, she may have been the last co-op customer to sign up for BPL. “I think they had this one last [modem] they dug out of storage somewhere,” she jokes.

In January, notes Loven, “We … sent notification letters to each of our customers explaining the situation. We wanted to give them plenty of advance notice so they could find another Internet provider.”

But are there any that meet 21st-century standards?

“I asked if there was another service provider,” says Sanders. “They said to call Frontier [Communications Corp.]. Frontier told me they don’t service this area; AT&T does. So I called AT&T. AT&T told me they don’t service this area; Frontier does.”

Off the map

“It feels weird to be in the United States and there are [developing] countries that have better Internet access,” says Sanders. “We’re in this weird zone, because we live in Madison but our address is Buncombe County. But we haven’t really been able to communicate that with anyone, because we actually haven’t been able to get in touch with a person that’s not in a call center.”

Service providers, says Mund, are “basically still telling us we’re not anywhere on the map.” Yet the high-speed highway runs right across the road from Sanders’ house.

Around 2008, says Merrill, “All of the sudden, they started all this construction on Leicester Highway. And I said, ‘They’re putting in a broadband line!’ … We were excited.”

But that optimism quickly faded.

“When they started doing construction,” remembers Metzger, “I asked one of the guys what was going on. He said, ‘They’re putting in fiber.’ I said, ‘We’re finally getting Internet!’ And he said, ‘Nope: it’s for Whisper Mountain.’ I said, ‘You’re going to go right by my road: You can’t put a T in there?’ He said, ‘Nope.’”

Whisper Mountain developer Charlie Ball says the gated community, whose master plan shows 89 upscale homesites, sits at the very end of AT&T’s service area. And when construction began in 2006, he pushed the utility hard to upgrade the existing copper line. Under franchise agreements, notes Ball, companies have to make periodic upgrades, but they decide on what kind of upgrade. “Their decision was whether to upgrade 6 miles of copper or put in fiber. It took a lot of doing to get it done; I had to lobby incessantly.” The problem, he continues, is that “There’s no switch between the central office [and the one at Whisper Mountain], and they only [install switches] based on demand.”

The switch, however, is what enables lines to be run to individual homes, explains Hunter Goosmann, executive director of the Education and Research Consortium of the Western Carolinas. The nonprofit provides fiber-based services in the “middle mile” (the segment between the core network and “last mile” providers) throughout the region.

Wire-based Internet, says Goosmann, gets to a specific house from a central office. And the one serving Sandy Mush is 6 miles away, in Leicester. “The fiber goes into a fiber distribution panel, then into a switch or a router, and then it will come out of that via copper connections that go into someone’s home.”

Sandy Mush residents say they’d be happy to cover the cost of installing such a switch. “We’re all sitting here with our pocketbooks open going, ‘We will pay for it!’” says Merrill.

Metzger concurs, saying, “I think there’s enough people on the road that if they said, ‘It’s going to cost this amount to run the lines,’ I think most everybody would kick in their share. Unless it would be like $20,000 to do it. That’d be a different story.”

Dollars and sense

Running 6 miles of overhead fiber-optics lines might cost $250,000, says Goosmann. But underground lines like the one on Leicester Highway are another story.

“Here in the mountains, if you kick the topsoil, it’s very likely you’re going to find granite, [which] easily adds another $100,000 to $200,000,” he notes.

Still, fiber has many advantages over copper lines, especially over long distances, Goosmann explains. It’s more durable; it can be bent and roped around corners; it can handle much more capacity at a higher speed; its signal doesn’t degrade as quickly; and, properly insulated, there’s almost no noise or interference.

But the upfront cost is greater, due largely to the material itself. The “fibers” are actually strands of glass, and the information they carry is in the form of light, unlike copper lines, which transmit electricity. Like Russian nesting dolls, fiber cables are made up of progressively smaller bundles of wires; all told, a cable may have up to 288 fiber-optic lines encased within it. “The average fiber line,” notes Goosmann, “is thinner than a human hair.”

Splicing a line to service an individual home or neighborhood means cutting each one of those fibers and installing extra equipment, which could cost “hundreds or into the thousands of dollars,” he estimates.

Thus, businesses are more reluctant to install access points in sparsely populated rural areas. An end-of-the-line connection like Whisper Mountain’s is more feasible, partly because it requires little to no splicing. “When you’re using fiber-optic cable, you’re sending light from one end to the other,” says Goosman. But with every connection, “That light signal gets degraded.”

“I wish we could help our friends and neighbors, but there’s no way,” says Ball. “We’re grateful to have the service and would love to help anyone we could … but we’re just a user; [AT&T is] the provider.” He says he “can’t imagine” how it would be financially feasible for the company. “There’s going to be way less than 1,000 users in that 6 miles” from the Leicester central office to the last switch. “You might get 100 customers.”

Wireless to the rescue?

Goosmann cites two key issues in expanding access in rural areas: “How far a house is from a central office, or is there an active point-to-point wireless service in the region?”

There are some wireless options in Sandy Mush, including a service provided by the Mountain Area Information Network, an Asheville-based nonprofit. There’s also Skyrunner, whose downtown Asheville building has “about a gigabit [fiber] connection coming in,” notes company co-owner Art Mandler. “Then, on top of the building, we have about a dozen radios that point in various directions, and then from those we make further connections into the community.”

Wireless providers buy bandwidth (delivered via a fiber connection) from providers like the Education and Research Consortium, using radio waves to give their customers Internet access.

“Having a fiber cable is the most secure and dependable connection you can have,” says Mandler. “But we’re filling a particular niche, which is crossing that gap where cable doesn’t easily go. … We can give them … 10 Mbps download speed with low latency.”

In addition, he notes, wireless is less prone to service interruptions, because there’s no long line that can be damaged or cut. And unlike satellite-based systems, Skyrunner’s radio equipment isn’t 30,000 feet in the atmosphere and thus is less susceptible to disruptions caused by things like bad weather. Furthermore, installation is relatively inexpensive.

But there’s one big catch: Wireless Internet can be transmitted only along lines of sight. “If you can’t see us directly,” says Mandler, “then you’re really not a candidate for the service.”

And that, unfortunately, is mainly case in Sandy Mush, he explains. “There are some points that could potentially be sites for broadcast, if there were a ridge that looks down on Sandy Mush that could ‘see’ one of our other broadcasts, and if we had inquiries from people who live in that area. But so far it hasn’t happened.”

Government’s role

“It’s a challenge for these larger companies,” says Mike Romano of NTCA — The Rural Broadband Association, “because they serve big cities and smaller areas, and these smaller areas aren’t really the focus of their investment or activity.” The national organization advocates on behalf of small, community-based service providers.

The federal Communications Act of 1934, which created the FCC, aimed to expand access to communications infrastructure.

“In the case of electricity and telephone,” says Romano, “we had programs through the Rural Utilities Service that helped finance cooperatives and small, privately held companies in the areas that larger utilities couldn’t find a justification to serve.”

French Broad Electric, for example, relied on low-interest loans from the Rural Electrification Administration, a forerunner of today’s Rural Utilities Service, to establish service to its customers.

A similar effort could help expand rural Internet access today. In a Jan. 14 speech in Cedar Falls, Iowa, President Obama said that clearing away the red tape and helping communities succeed in a digital economy is one of his goals for 2015. Cedar Falls Utilities, a group of community-owned services, offers Internet customers speeds of up to 1 gigabit per second (1,000 times faster than 1 Mbps).

“Small, locally owned companies want to make the transition to broadband,” says Romano, “but for the same reasons, it’s hard to deploy. It would seem like we should be looking to the programs that have worked before — appropriately updated — rather than trying to reinvent the wheel.”

Mixed results

Recent efforts by various government entities, however, have been spotty and sometimes counterproductive, due to insufficient oversight and coordination.

“What the FCC is doing now in areas served by larger companies is to give them an incentive,” Romano explains. “So if you serve these customers in N.C. with at least 10 [Mbps] broadband, they’ll give you this much money over a six-year period. If the company declines it, that money will essentially go up for auction. Some of the concern is if it goes to auction, people will still look for places that make the best business case rather than the entirety of the map. Some rural areas might get served, but the most unattractive become harder still to serve.”

Another federal government initiative, the Broadband Technology Opportunities Program, has supported useful projects in N.C. and elsewhere but has also had significant problems. Part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, the $4 billion program provides grants to communications, broadband and electrical companies to run wire to rural areas.

About $104 million of the money went to the Microelectronics Center of North Carolina, a state-initiated nonprofit, for its Golden Leaf Rural Broadband Initiative. The project helped connect universities, community colleges, hospitals, schools and libraries, including the Leicester branch.

Goosmann’s Education and Research Consortium also benefited. “We got about $15 million of that,” he says, enabling the organization to extend its fiber networks in the area.

Other stories, though, are not so rosy.

A Feb. 11, 2013, New York Times story titled “Waste is Seen in Program to Give Internet Access to Rural U.S.” detailed cases of fraud, abuse, mismanagement and shortsighted planning in the Broadband Technology Opportunities Program. In one case, an 11-student school in Agate, Colorado, received a fiber-optic Internet connection even though it already had two; in another, a subcontractor used part of a $12 million grant to run fiber through the neighborhoods where its employees lived.

“Nationally, $594 million in spending has been temporarily or permanently halted, 14 percent of the overall program, and the Commerce Department’s inspector general has raised questions about the program’s ability to adequately monitor spending of the more than 230 grants,” the article noted.

“BTOP was a particularly interesting program,” says Romano. “What it ended up being used for, in many cases, was long-haul runs of fiber where people could sell it, on profitable routes that might also happen to run through a rural area connecting some schools or libraries. … But it didn’t really connect the rest of the community. … They built fiber to a school, but they didn’t build fiber to all the houses that … the school serves.”

He adds, “If you cherry-pick customers and just take the schools and libraries and leave the rest of the community, it’s going to become harder for someone to make a business case just to serve what’s left of the community.”

That’s the situation facing French Broad Electric, which has been seeking alternatives to its BPL system for years with no success. “There seems to be a lot of money out there for rural Internet projects on the surface, but it’s almost impossible to get, due to the restrictions and limitations set forth in the application process,” says Loven.

“We’ve applied to three different sources for funding a [fiber-to-home] project but haven’t been selected by any of them. The high-speed Internet business is risky, and in our area, where the customer density is low and other technologies are emerging overnight, a large amount of the funding has to come in the form of a grant, or there is simply too much risk.”

Loven says the co-op is “still evaluating every opportunity to see if we can find a suitable replacement that’s affordable. But as of today, that option is simply not out there.”

Watching the world move on

Across the country, many remote mountain and rural communities are even worse off than Sandy Mush in terms of broadband access.

And what’s needed, says Romano, is not just reliable financing (perhaps through the Rural Utilities Service) but also “a sufficient, predictable and sustainable support mechanism that’s aimed not only at getting networks out there but keeping them out there.” For nearly 20 years, he continues, “The FCC has tried to find other ways of stimulating network investment in rural areas, and none has proven as widely successful as this particular combination of programs.”

But if that doesn’t happen, Romano emphasizes, the key will be “reconciling all of these different existing programs to make sure they’re working well with one another. That’s what we saw with RUS and [the Universal Service Fund] in the past. … Now, everyone seems to be coming up with the ‘next big thing’ to solve the rural broadband challenge, and they’re never coordinated very well. No one thinks through what the implications are with the rest of the community or other programs.”

Goosmann agrees. Getting quality Internet to rural communities, he predicts, will take “a combination of fiber, copper and wireless. It’s not one solution with the mountains: It never is.”

Meanwhile, in neighboring Yancey and Mitchell counties, precisely the kind of collaboration Romano and Goosmann describe has given residents of those rural areas some of the fastest Internet in the country (see sidebar, “Yancey, Mitchell Roll Out Fastest Countywide Internet in N.C.”).

For Sandy Mush residents, however, at least the immediate future seems to promise continued digital isolation.

“We can either go back to dial-up or very spotty satellite service,” says Mund. “I mean, I’ll do it, but we literally have no viable option come June.”

And a frustrated Merrill notes, “We’ve really started to thrive because of the Internet. Once it’s cut off, how am I going to make a living? I put so much money into my [home-based] business, and it’s just now getting to the point where it’s starting to pay off, and now…”

Metzger, meanwhile, sounds a similar note. “Part of me says, ‘You made the choice to live out in the boondocks,’ and yes, I made that choice. … But at the same time … it goes right by our road. I get it, you know? There’s only 14 houses instead of 1,400. But it just blows my mind that I can’t take advantage of something everyone else has.”

“It’s funny,” Mandler of Skyrunner said in a recent phone interview. “While we were talking I was sort of clicking around on my topography map, looking at what it would take to cover that Sandy Mush Valley. There’s a ridge there to the north called Little Sandy Gap. And just to the west of that is a pretty tall peak that has kind of a great reaching view across both directions. I bet if you got up there…”

Skyrunner, our local gem, comes highly recommended!

We moved to Hendersonville, near Edneyville Line from NJ, are 72 and found cable service unavailable. We had HughesNet, but speed, delays, and problems, were horrific. We cancelled Hughes and went to a Verizon 4G Wireless Modem giving us 30 GB/month, barely enough. We have DIRECTV as well, and are paying over $400.mo., without a land line phone, as compared to NJ @ $138.mo. which included telephone. While in NJ we had a “Universal Service” line item fee, attached to both our phone and cable bills, to cover Universal Services, that would in theory provide these services to rural areas. Now we find that we must not have paid enough, to get to this rural area?

Couldn’t AT&T tap into their fiber and install a WIFI router for area residents?