by Virginia Daffron and Lee Elliott

When Duke Energy announced last year that it was canceling controversial plans for a hugely intrusive 45-mile transmission line to a new power plant in upstate South Carolina, local environmentalists hailed it as a victory. In response to massive public outcry, the utility instead proposed two natural gas-powered units to replace the coal-fired generators at Lake Julian, with a third generating unit to be built if peak power demand continues to grow in the region.

Proponents have long touted natural gas as more environmentally friendly than coal, though more recent evidence has challenged that assertion. And while environmental advocates such as MountainTrue and the Sierra Club applauded Duke’s decision to scrap the transmission line, they urged the utility to accelerate the transition to renewable resources rather than continuing to invest heavily in fossil fuels.

Nonetheless, state regulators approved Duke’s plans (minus the third generator), based in part on the utility’s pledge to make every effort to slow the growth of local power demand. Soon after, Buncombe County, the city of Asheville and Duke Energy finalized plans for an innovative 15-member task force to chart the region’s energy future.

But what wasn’t heard much during this feel-good narrative was a word that’s generated its own fair share of controversy in recent years: fracking. Hydraulic fracturing, which injects water and various chemicals into shale formations to extract oil and natural gas, has been linked to groundwater contamination, air and noise pollution, human health concerns and even earthquakes (see sidebar, “Fracking 101”). Unbeknownst to many locals, it appears that fracking is already the source of much of the natural gas consumed here — and large-scale projects are underway to bring in even more fracked gas.

Yet when Xpress began investigating, we found local energy and environmental leaders either unaware of the source of the gas that will power Duke’s new Lake Julian plant or unwilling to discuss it.

And Jim Warren of NC WARN, who’d called attention to the issue even before Xpress confirmed the source of the fuel, said other local environmental groups criticized him for calling Duke’s new Lake Julian facility a “fracked gas plant.” The way he sees it, “Everything that Duke Energy or any user does that increases the use of gas is increasing drilling and the use of shale gas. There is virtually no growth in the conventional gas supply.”

Just the facts…

It ought to be a straightforward question. In documents filed with state regulators, Duke Energy said it has long-term contracts with PSNC Energy to supply the Lake Julian plant, so it seems reasonable to expect that the giant utility would have some knowledge of where PSNC gets its gas.

Or maybe not. Jason Walls, Duke’s local government and community relations manager for the Asheville area, is one of the Energy Innovation Task Force’s three facilitators. Asked about the source of the gas, Walls said, “I don’t know anything about that.” Pressed further, he advised, “You’ll have to ask PSNC about that.”

Duke Energy spokesperson Meghan Musgrave Miles gave a similar response to an email requesting information. “You’d need to reach out to PSNC about that question, since they are leading this project,” she wrote.

Xpress also contacted task force facilitator Julie Mayfield, who’s co-director of MountainTrue and also serves on the Asheville City Council. She’s been involved in the nonprofit’s efforts to defeat Duke’s plans for the transmission line and reduce the size and number of gas units at Lake Julian.

Asked about the fuel source, Mayfield said, “From what I understand, it’s coming from offshore drilling in the Gulf of Mexico.” Asked about planned pipeline projects that would deliver shale gas from West Virginia and Pennsylvania to North Carolina, Mayfield said she wasn’t aware of them.

Buncombe County Commissioner Brownie Newman, a solar energy entrepreneur, represents the county on the task force. He did not respond to calls seeking comment on the source of the gas.

But Amy Knisley, the chair of Warren Wilson College’s environmental studies department, is concerned about the apparent confusion and lack of transparency. “It’s implausible to think that Duke Energy wouldn’t know the source of the natural gas they are contracting to purchase,” she pointed out. “They ought to know, and the public ought to know too. Because it’s not irrelevant to public health and environmental health: It is relevant, and it has implications.”

Going with the flow

Calls to PSNC Energy, a subsidiary of the Cayce, South Carolina-based SCANA Companies, were routed to spokesperson Persida Montanez. After referring some questions back to Duke Energy, she eventually confirmed that PSNC sources its gas from the Transco (short for Transcontinental) pipeline. In an email, Montanez wrote, “I’d reach out to Transco for the where and how.”

Eventually, the trail led to Christopher Stockton, a spokesperson for the Tulsa, Oklahoma-based Williams company, which owns and operates the pipeline.

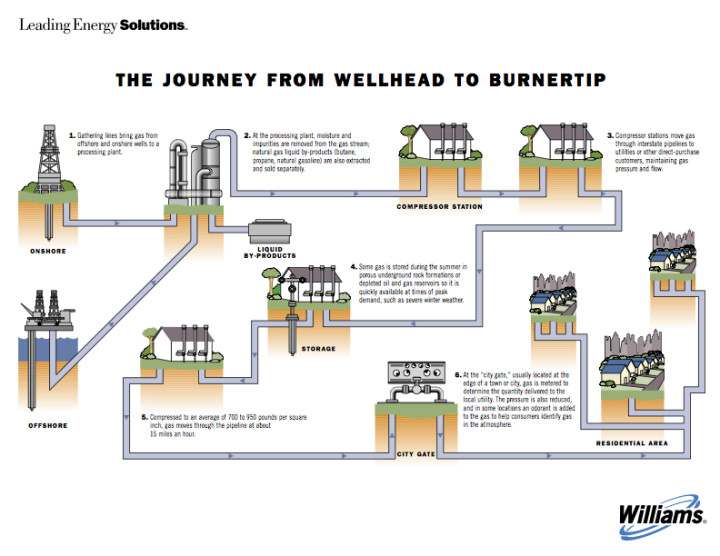

Natural gas, he noted, is coal’s colorless, odorless, cleaner-burning cousin. And while both require major infrastructure to travel from their source to the eventual users, the 10,000-mile underground pipeline that brings natural gas from Texas and the Gulf Coast north to New York City stops no traffic and makes no sound as it delivers 10 billion cubic feet of gas each day.

The Transco pipeline actually consists of multiple lines running parallel to one another, said Stockton. They range in diameter from 20 to 42 inches; compressor stations spaced about 100 miles apart keep the flow moving, mostly south to north.

The gas comes from various sources, including offshore drilling platforms in the Gulf of Mexico. But the vast majority, said Stockton, “is produced through hydraulic fracturing.” And while a lot of it is sent north to New Jersey and New York, he continued, “It is fair to say that much of the gas we deliver to North Carolina is probably produced through hydraulic fracturing.”

According to a Williams document provided to Xpress by Jan Larsen, director of the Natural Gas Division of the North Carolina Utilities Commission’s Public Staff, the company sources natural gas from shale deposits in Texas, Oklahoma and Arkansas. “The amount of gas originating from [offshore drilling in] the Gulf has steadily declined,” Stockton explained.

Transco doesn’t sell gas directly to homes and businesses; local distribution networks along the pipeline’s route handle that part of the supply chain. PSNC Energy serves over half a million residential, commercial and industrial customers in North Carolina.

In a February application for a general rate increase, PSNC noted that to meet future needs, it “has subscribed to 100,000 dekatherms per day on Transcontinental pipeline’s Leidy Southeast expansion project, 100,000 dekatherms per day on the proposed Atlantic Coast Pipeline, and 17,250 dekatherms per day on the city of Monroe’s intrastate pipeline.” Monroe’s supply also comes from Transco, said Montanez.

Comin’ round the mountain

According to Jim Fox, director of UNC Asheville’s National Environmental Modeling and Analysis Center, the Southern Appalachian region is isolated from conventional power sources twice over: first by its relative lack of fossil fuels, and second by the difficulties of transporting fuel into the mountains from elsewhere.

The Asheville area, Fox explained, lies outside of PSNC’s main pipeline corridor. A 26-mile spur line runs from Mill Spring to South Asheville.

Currently 8 to 12 inches in diameter, it’s being upgraded to a 20-inch pipe that will run through the PSNC’s existing right of way, said Montanez. The first phase of the expansion is slated to enter service this summer. Construction to connect the new pipeline to the Lake Julian plant is expected to take place between October 2017 and May 2018.

“To be clear,” she emphasized, “PSNC Energy’s pipeline replacement project was scheduled to occur before Duke’s plans to build natural gas plants in Asheville were announced. Duke Energy is a customer of this pipeline, just like any other large industrial customer. Our company has served Duke’s existing peaking plant [at Lake Julian] for over a decade.”

Just another fossil fuel

Local pipeline connections are only one piece of the puzzle, however. Planned upgrades to the interstate distribution network could also affect both the source and the total amount of natural gas entering the state.

Williams’ proposed Atlantic Sunrise project would expand the Transco network, which was originally built in the 1950s. Additional pipeline in Pennsylvania would connect with new hydraulic fracturing sites in the Marcellus Shale, which Reuters called “the fastest-growing natural gas market in the United States” last year. Other pipeline and equipment upgrades would increase what Transco terms “bidirectional flow” — the company’s ability to send gas both south and north from the Pennsylvania shale fields.

Much of the industry’s growth, noted Stockton, is coming from new natural gas-powered electrical generating plants, many of them in the Southeast. Making Pennsylvania’s fracked gas available to residential, commercial and industrial customers in the Southeast will provide greater reliability and lower prices, he said.

Meanwhile, the planned Atlantic Coast Pipeline would be the first major natural gas line serving Eastern North Carolina. And though it wouldn’t directly feed the Asheville area, the project — whose North Carolina portion would be owned by Piedmont Natural Gas and Duke Energy — highlights the utility’s pivot toward natural gas.

Duke is in the process of acquiring Piedmont for $4.9 billion; pending regulatory approval, the parties hope to close the deal later this year. And when the PNG acquisition is factored in, Duke’s overall investment in natural gas could exceed $25 billion in the coming years, according to NC WARN. The group has filed a lawsuit opposing the proposed purchase, arguing (among other things) that increasing Duke’s energy monopoly in the state will have a negative impact on consumers, noted Warren, the nonprofit’s executive director.

Other environmental groups are also concerned about the planned projects. Kelly Martin, associate director of the Sierra Club’s Beyond Dirty Fuels campaign, said her organization has filed lawsuits to block the construction of both pipelines.

Atlantic Sunrise, she maintains, “will destroy wetlands and streams throughout the Appalachian region. The scope and scale of the pipelines being built out of the Marcellus Shale are a major problem for the climate.”

Martin’s campaign focuses on keeping fossil fuels in the ground; stopping pipeline expansions, she explained, is an effective way to prevent natural gas from coming to market. “Natural gas is just another fossil fuel. It’s not our vision of what clean energy is, and what our energy future looks like in this region.”

Changing the equation

Duke Energy’s Nov. 4, 2015, announcement about pulling the plug on the proposed transmission line and building new gas-fired units at Lake Julian stresses the plan’s environmental benefits. The new plant will significantly decrease greenhouse gas emissions, including a 60 percent drop in carbon dioxide, the press release explains. Burning fossil fuels increases the CO2 concentration in the atmosphere, which traps heat, contributing to the greenhouse effect. Carbon dioxide is a major contributor to rising global temperatures, since it persists in the atmosphere for thousands of years. Sulfur dioxide will be reduced by an estimated 90 to 95 percent, while nitrogen oxide will be reduced by an estimated 35 percent.

Other environmental benefits the utility cites include eliminating mercury byproducts, a 97 percent reduction in water withdrawals from Lake Julian and a 50 percent reduction in water discharges. Taking its coal-fired plants out of service will also enable the company to stop generating coal ash at the site and complete its cleanup of the existing coal ash ponds.

But while those benefits sound compelling, there’s no perfect choice when it comes to extracting and using fossil fuels, says Fox. “We don’t like mountaintop removal for coal mining; we don’t like fracking; we don’t like the [2010] Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf,” he observes.

And though natural gas, which is 99 percent methane, gives off less carbon dioxide per unit of energy produced, mining and transporting it poses another problem: leakage from wells, abandoned mines, pipelines and compressor stations. In April, the Environmental Protection Agency concluded that methane production and distribution releases 27 percent more of the gas than previously estimated.

According to Stockton, the Williams spokesperson, three-quarters of the methane released in the U.S. comes from agriculture. But the EPA now says the energy industry is the country’s biggest emitter. Methane is problematic because it traps far more heat per molecule than carbon dioxide. “Methane’s lifetime in the atmosphere is much shorter than carbon dioxide’s, but CH4 [methane] is more efficient at trapping radiation than CO2,” the EPA’s website notes. “Pound for pound, the comparative impact of CH4 on climate change is more than 25 times greater than CO2 over a 100-year period.”

The answer, says Martin of the Sierra Club, isn’t switching to a supposedly cleaner fossil fuel. “We need to keep fossil fuels in the ground to avert the worst effects of climate change, and fracking releases methane, which is a very potent greenhouse gas,” she explains.

Bridge to what?

But whether the gas that powers Duke’s new plant comes from fracking in Oklahoma or Pennsylvania or deep-water drilling in the Gulf makes little difference, argues retired physician Richard Fireman, who’s now the public policy director of the Alliance for Energy Democracy. And during the fast-track approval process for Duke’s new Lake Julian plant, the longtime environmental activist recalls, the utility was in no hurry to correct the environmental community’s impression that the gas supply for the new plant wasn’t tied to fracking.

Both extraction methods, he points out, have significant negative impacts. “Methane is a potent greenhouse gas, so whether it’s coming from deep water or hydraulic fracturing, it’s polluting the atmosphere. The main difference is that fracked gas is harming human communities. In the case of deep-water drilling, if there is an accident, we’re harming marine communities.”

Told about the source of the Transco pipeline’s gas, task force member Sonia Marcus said, “This is a more formal confirmation of something that’s been very clear for a long time, which is that if you’re sourcing natural gas in the United States right now, there’s a very high likelihood that all or most of that is coming from hydraulic fracturing operations.”

Marcus, who is UNC Asheville’s director of sustainability, adds that though Duke and regulatory officials may not have been explicit about the extraction method, “If you’ve been paying attention to energy developments in this country over the last five to seven years, you know the fracking industry has completely changed the profile of our fossil fuel consumption.”

Which brings us back to the argument made by groups calling for a more profound transition to renewable energy sources.

“People argue that natural gas is a good so-called ‘bridge fuel,’” notes Knisley of Warren Wilson College. “And that’s an interesting concept, but it only works if we’re building the other side that the bridge is supposed to be getting to. If the bridge just gets longer and longer — which, at the moment, looks like what’s going to happen — we just stay on the bridge. We never get to where, allegedly, we think we’re going.”

https://mountainx.com/blogwire/duke-energy-to-retire-asheville-coal-plant/#comment-2401930

Great review of an often confused subject, making it a little less confusing. As a long time student of energy economics, I agree most with Sonia Murcus’ comments. Any new gas demand in the US is being fulfilled on the margin by fracking. And he that the plants will be built we must get behind and give energy to the Energy Innovation Task Force’s efforts to insure we don’t build another one and also to reduce the utilization of the gas plants as much as possible. To have a livable world we need to do everything we can to reduce and eliminate our CO2 emissions and methane leakage. A gradually increasing user fee on carbon with a methane leakage adder adopted at a national level would be a great complement to our local efforts.

LOL, because like the air in other parts of the world like is in a vacuum lulz. But the irony here is that you’ll literally tax people to death and weaken the nation ever further ALTHOUGH not one other polluter nation is stupid enough to follow. And what’s worse, that some of those other nations will destroy their environment to build up their military power. But hey whatever makes you FEEL better. You do know that US coal is being shipped overseas to be used in less environmentally clean plants, right? But hey, that bubble in your mind just ignores is.

You bring up some great points. Fortunately, the program that I support, Carbon Fee and Dividend (CF&D) already addresses those valid concerns. Technically, CF&D is more of a user fee than a tax. This is because the fee does not increase government revenue but instead bypasses the government and goes back to the people in the form of a monthly check(after a diction for administrative cost). This is very similar to the Alaska Permanent Fund, which distributes a fee assessed on oil production to the citizens of Alaska. A recent study shows that about 2/3 of the people are better off, and that over 85% of people in WNC who are in the lowest 20% of incomes are better off. The people who are worse off are well able to afford it, since they tend to be in the top 20% of incomes. So the design of this plan takes into account concern that it will “tax people to death”. In fact, it’s quite the opposite. Leading conservatives support this plan.

This program is designed also to be part of how we comply with the agreement signed inParis by over 180 countries. So as long as we are taking strong action to move off fossil fuels, we can pressure other countries to live up to their commitments as well. And the CF&D proposal contains a trade adjustment mechanism to add to the cost of other countries trying to export to us if those countries are not adopting this or a similar program. CF&D will actually help the US competitive position and the balance of trade.

You can find out more about this at http://www.citizensclimatelobby.org.

Cant have it all ways folks.