By Jack Igelman, originally published by Carolina Public Press. Carolina Public Press is an independent, in-depth and investigative nonprofit news service for North Carolina.

In 2013, the U.S Forest Service launched the assessment phase of its land management plan revision process for Western North Carolina’s Pisgah and Nantahala national forests.

On Friday, nearly a decade later, the agency revealed its strategy that will dictate the overall management framework of the forests, including future land designations, such as wilderness. The strategy will also address the forests’ health and resiliency and their spectrum of resources.

In February 2020, the Forest Service released a proposed land management plan with four alternative management schemes.

The Forest Service received and analyzed a substantial volume of public comments following the release of the proposed plan and has used that feedback to develop and select a new management option: Alternative E.

The agency also released a final environmental analysis of the alternative, known as the environmental impact statement.

However, the agency’s decision isn’t final. One more step remains before the Forest Service authorizes the revised planning document as its blueprint for the management of more than a million acres of public forest in Western North Carolina for the next two decades.

A 60-day objection period is underway, followed by a 90-plus-day resolution phase. The Forest Service said it will ultimately finalize the management plan in mid-2022.

Updated federal forest planning rules adopted in 2012 and other federal regulations guide the process, which is intended to span a three- to five-year period. In fact, Pisgah and Nantahala were among five national forests that were first adopters of the 2012 rules.

Navigating the new regulations amid substantial public participation prolonged the planning process, with the pandemic adding further delays.

Forest Supervisor James Melonas said public involvement is the cornerstone of the planning process and helped form a better plan.

Melonas was named supervisor of the four federal forests in North Carolina in December 2020 after a three-year stint in New Mexico. Before that, he served as the assistant supervisor in North Carolina.

“We feel very good with where we’ve landed with the plan and that it advances all interests and sets us up for the next generation of management,” he said.

“It’s a great opportunity to move forward together into implementation.”

What’s in Alternative E?

The revised land management plan, once signed, will replace the current plan drafted in 1987 and substantially amended in 1994. In the three decades since, Forest Service planner Michelle Aldridge said conditions within and around the forests have transformed.

Among the changes are population growth and development on the boundaries of both national forests, which have accelerated the surge in demand for recreational resources such as trails, parking and camping facilities.

Ecological conditions have also altered substantially since the last plan was adopted. Among the threats are the consequences of climate change, the spread of invasive pests and disease, the lack of natural and managed fire and an aging forest.

Combined, the ecological changes have damaged the health of the forest and created a mounting challenge for managers to ensure access to users and to target the desired ecological conditions of the two national forests.

A hallmark of Alternative E, Aldridge said, is a more tailored approach to managing such a vast section of the public domain by organizing the forest in distinct ecological units.

Aldridge, who joined the planning effort in 2015, said the revised plan creates a clear vision for each ecological unit within the forest.

“It emphasizes the uses and places that are important to people and reflects the values people have for different places,” she said.

The approach is contrary to the plan amended in 1994 which set standards, guidelines and goals for the entire forest as a single ecological unit.

According to the Draft Record of Decision, a 91-page document that outlines the rationale for the decision, Alternative E will increase emphasis on prescribed fire, establish an expanded network of old-growth forest, promote sustainable trail development and focus on addressing a backlog of road maintenance by decommissioning unneeded roads and expanding access in areas with high demand.

Melonas said Alternative E best positions the agency and the public to address the challenges they anticipate in the next two decades that revolve around four themes that emerged during the public planning process: connecting people to land and sustainable recreation, sustaining healthy ecosystems, providing clean and abundant water, and partnering with others.

Indeed, the forest plan will rely on an additional “tier” of objectives that require the support of public and private partners.

The Forest Service demonstrated recently that this approach may succeed in Western North Carolina. On Jan. 15, the Forest Service, the G5 Trail Collective and other community partners conducted a groundbreaking ceremony to mark the start of construction of the 42-mile Old Fort Trails Project within Pisgah National Forest in McDowell County.

Lisa Jennings of the Forest Service said the groundbreaking for the community-driven project is a “watershed moment.”

“It represents a tidal shift in what’s possible on our public lands and shows what happens when a community of people from diverse backgrounds comes together to dream big about their future,” she said.

Conflicting viewpoints

The COVID-19 pandemic wasn’t the only hurdle facing Forest Service planners and the public over the course of the revision process.

In earlier stages of the planning process, conflict centered on public land designation, such as wilderness, and disparate views regarding the ecological restoration of forests and wildlife habitat.

In 2014, during a round of public meetings throughout the region, confusion reigned after the Forest Service proposed a management scheme that appeared to propose timber harvesting activities on two-thirds of the forest.

The scheme alarmed several conservation groups.

Alternative E identifies 459,000 acres of land suitable for timber harvesting activities.

The plan itself provides the overarching strategy and goals for the future of the forest; however, it’s on the project level where the agency executes specific actions.

The public heavily scrutinizes timber projects to support local economies or for restoration. Such projects would likely occur on relatively small units of the forest.

In 2015 and 2016, tension erupted after 40 organizations signed a memorandum of understanding supporting the creation of two proposed national recreation areas, submitted to the Forest Service as a public comment.

Some members of the public who had engaged in the planning process were surprised by the proposal, leading to division among some advocacy groups.

And in 2013 and 2014, 12 North Carolina counties passed nonbinding resolutions opposing the addition of designated wilderness, the highest form of federal land protection, within their borders.

The revised plan includes recommendations for the National Wilderness Preservation System and waterways suitable for inclusion in the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System.

Alternative E recommends the addition of 49,098 acres of wilderness on 14 areas of land. While these acres will be managed as wilderness for the duration of the future plan, permanent protection in the wilderness system would require an act of Congress.

Wilderness advocates may be disappointed. Though Alternative E recommends more wilderness acreage than proposed alternatives A and C, alternatives B and D called for more.

“The areas that we’re recommending in the final plan are based on comments and our own expertise on how they would be managed,” Melonas said.

The agency also considered where wilderness recommendations would lead to conflict with current users or communities.

“Our recommendations have the highest wilderness characteristics, and if Congress decided to designate them tomorrow, they would be strong additions to the wilderness system,” he said.

Kevin Colburn of American Whitewater said the new plan identified eight additional rivers suitable for Wild and Scenic River protection, including the West Fork of the Pigeon River, Santeetlah Creek and the South Toe River. In addition, the plan will also carry forward 10 rivers identified as suitable in the 1994 plan.

However, Colburn said, the plan excludes “some outstanding streams like the North Fork of the French Broad and the headwaters of the Tuckasegee River.”

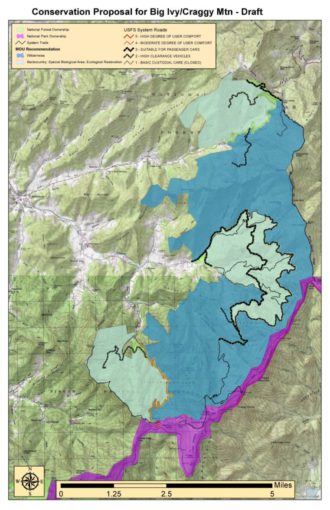

Will Harlan of the Friends of Big Ivy told Carolina Public Press he is pleased the plan recommends an expanded wilderness area and a “forest scenic area” in Big Ivy and the Craggy Mountains in Buncombe County in recognition of its outstanding and unique ecological and recreational qualities.

He is hopeful that the recognition will ultimately lead to the creation of the Craggy National Scenic Area, which would require congressional action and provide special protection.

The Friends of Big Ivy has fostered a coalition of more than 150 organizations and businesses supporting the idea.

“This is a rare opportunity to show that communities matter, democracy still works, and public lands can bring us together,” he said.

Resolution

Aldridge said the Forest Service focused on including the “thousands of ideas” that emerged during the planning process.

Among the key contributors to the future plan, she said, were Federally Recognized Tribes, including the Eastern Band of the Cherokee Indians.

The Cherokees will consult on the use of “traditional ecological knowledge” to help design future projects by applying traditional timber management strategies and techniques for harvesting sustainable nontimber forest products, such as ramps.

In addition, many of the ideas were generated by collaborative groups that the agency said were crucial during the revision process.

Melonas cited the creation of the Stakeholder Forum in 2015, a Forest Service-funded collaborative effort, with helping reboot the effort. In addition, the Nantahala-Pisgah Forest Partnership was formed at the start of the revision and will focus on shaping specific projects within the forest.

“There was a time when there was a lot of tension,” he said.

“We did an intentional reset to focus on relationships. That was a huge amount of work but was essential. This isn’t just about the plan; it’s about the relationships we’ve built over time.”

Over the course of the planning process, a common theme emerged: Many organizations — including the forest industry, conservation organizations and local governments — jelled around the view that ecological restoration of the forest is vital for all users, from hunters to kayakers.

Colburn of American Whitewater captured that sentiment when he told CPP in 2019 that “there’s a lot of interest in making parts of the forest younger and making parts of the forest grow older for many different reasons and values. One of the nuances we found is that ecological restoration as a concept meshes with pretty much everyone’s values.”

Relative to other proposed alternatives, “E” emphasizes restoring a mixed-age forest requiring the creation of more open spaces and young forest habitat that remains underrepresented in the Pisgah and Nantahala forests.

David Whitmire of the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Council said his grassroots coalition of hunters and anglers needs time to digest the details of the plan; however, his initial impression is that the objectives focused on restoring wildlife populations are “pretty solid.”

“The tiered approach is a big opportunity to build wildlife populations to the scale they might have been 30 years ago,” he said.

Work ahead

Melonas said the release of the land management plan comes at a good time, especially for an agency struggling to expand its funding and resources.

“All the pieces are in place to move toward implementation with the partnerships we’ve developed,” he said. “The stars are aligning for us to leverage resources to get more work done on the ground.”

He is referring, in part, to federal dollars that may arrive via the Biden administration’s infrastructure plan and the Great American Outdoors Act, which focuses on funding the backlog of projects throughout the U.S. public land system.

The conclusion of the planning process will also free up resources within the Forest Service that have supported the forest plan development and analysis.

“It’s a career achievement for folks on our team, but now they can focus on their programs and working with partners to get work done,” Melonas said.

“I feel good … that we’ve been able to do the right thing based on science and ecological knowledge and incorporating all the interests that have come to the table.”

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.