By Liora Engel-Smith, North Carolina Health News

A freezing February rain pummels the hospital windows, but for once, it won’t reach Donna. The 52-year-old cannot remember the last time four solid walls and a roof protected her from the bitter Appalachian winter.

The bacterial infection that brought her to the intensive care unit in the middle of the night weakened her, but Donna was well enough to appreciate the perks her illness bestowed. She could sprawl, rather than recline, when she slept. The bathroom, with its running water and door that closed, offered more comfort and privacy than any tree in or out of Macon County. She had enough food for once.

And most of all, Donna was warm — not a small feat for winter in rural Western North Carolina, where temperatures often drop below freezing at night.

Angel Medical Center, the only hospital in Franklin, rarely inspires praise in these parts. The decades-old building on Riverview Street is too outdated to meet the community’s needs, hospital administrators said when they described plans for a $65 million replacement.

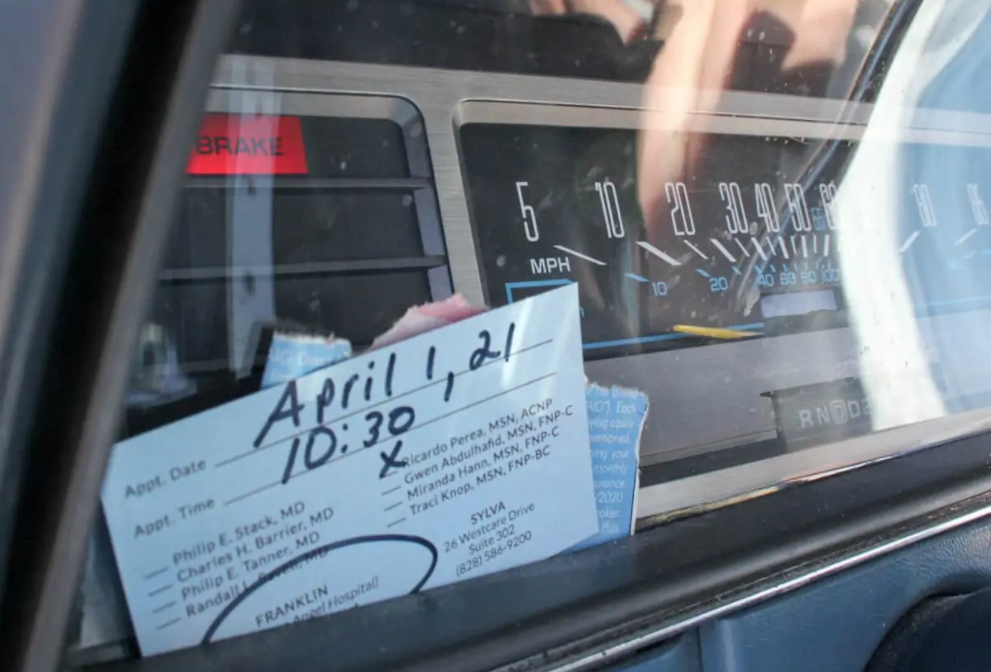

Yet Angel is more than enough for Donna and her partner, C., who asked to remain anonymous. It’s better than the tarnished 1987 Oldsmobile they call home.

A gift from a former patient she cared for years ago, the cruiser is a relic from another life, back when Donna and C. were getting by. They lived in a squat one-bedroom trailer at the edge of town. The rent — $145 weekly — consumed 37 percent of Donna’s salary. Money was tight even with food stamps and the money C. made in his job as a dishwasher, Donna said. On paydays, Donna would buy a fifth rum to get her through the week. If she was rationed it carefully, the $10 or $12 bottle would keep her numb and pain free for a whole week.

Little by little, the bottom fell out. They missed utility bills and rent payments. Then they had car trouble. Then, medical emergencies. Finally, they were evicted, and not for the first time.

The two have teetered on the edge of homelessness for the better part of two decades. By the time the Oldsmobile became their only shelter, the two had amassed three court-mandated evictions between them. At least seven other eviction filings prompted the couple to leave before the Macon County magistrate issued summary ejectments.

Donna and C.’s housing instability predated the economic crisis of the coronavirus pandemic.

They weren’t alone.

In 2001, the year of Donna’s first eviction in Macon, nearly 1 in 5 renters in the county had an eviction filed against them. About 1 in 50 had been evicted from their homes that same year. Across the state, the number of court-mandated evictions that year amounted to roughly 50 each day.

These numbers don’t reflect the untold number of renters who leave as soon as their landlords threaten to take them to court.

At 4.61 percent in 2016, North Carolina ranked 5th in the nation in its eviction rate, almost twice as high as the national eviction rate of 2.34 percent that year, according to Eviction Lab, a research project out of Princeton University.

“North Carolina was already at the top of the top largest evicting areas,” said Emily Benfer, a visiting professor who studies the health implications of housing instability at the Wake Forest University School of Law. “So that says a lot about where we probably are now.”

A growing problem

Housing is more than a roof and a place to store valuables. It has important implications for mental and physical health according to the federal Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Forced moves, whether by court order or for lack of rent, can also expose tenants to unsafe housing conditions as they scramble to find another home following an eviction. To avoid homelessness, tenants may settle on substandard housing that can exacerbate chronic conditions such as asthma and allergies. They may rent bug- or rodent-infested homes, rooms with mold or poor heating.

Being without a home often has its own health risks, according to research compiled by the National Health Care for the Homeless Council. Exposure to the elements, as well as lack of healthy foods and medicine can make the homeless vulnerable to infections such as pneumonia. Lack of sanitation can turn minor injuries into major infections and chronic health conditions, such as diabetes and heart disease are hard to manage in the streets. These and other reasons put the homeless at risk for major illness and early death.

Though homelessness is often viewed as an urban issue, housing instability outside of cities is growing according to the National Coalition for the Homeless. In the most recent report issued by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, fully 18 percent of the nation’s homeless lived in rural areas, a rate that has steadily grown over the past two decades.

Data collected locally by the North Carolina Coalition to End Homelessness each year detail the misery. In 2015, the first year North Carolina’s annual point in time count of homeless people broke down numbers by county, 18 residents of Macon County were listed as homeless, with a total of 3,021 people lacking shelter in the state’s non-urban counties. By 2020, even as the state’s economy improved, Macon listed 82 homeless people, and the annual count found a total of 3,185 rural North Carolinians lacked housing.

The number of homeless people in Macon County is likely much higher, since the annual point in time counts, where volunteers count the homeless on a single night in January, can miss residents who camp outside of town, said Bob Burke, executive director of Macon New Beginnings, a Christian service organization that works with the county’s “homeless and nearly homeless.”

“You can’t come up with a number right now,” he added. “They’re staying on the mountain right now and I’m not going to climb that mountain to count somebody in the woods.”

In most cases, remote communities do not have enough resources to meet the needs of their poor. Rural homeless shelters are rare and those who don’t have family members or friends willing to take them in are often forced to sleep outside year round.

While some rural communities have food pantries or homeless prevention programs, these initiatives are usually limited by funding and geography. Without robust social and economic guardrails, even a small crisis — be it illness, job loss or car malfunction — can push someone into homelessness.

Coming up short

The Oldsmobile was the answer to a prayer Donna rarely spoke out loud. When she turned the ignition key in her 1994 Dodge Spirit each day, she half-pleaded, half-prayed for the car to deliver her from point A to point B.

The tan beater was living on borrowed time and Donna knew it. A $400 purchase from a friend of a friend, the Dodge had a mangled back door from what Donna suspected was a run-in with a deer. Donna and C. did not have the money to repair or even maintain the pockmarked car, but the Dodge stubbornly clung on as it heaved back up Mount Cullowhee at the end of each day.

Mountains take a particular toll on cars. Steep slopes are the norm here, as are cracked asphalt and potholes. Sooner or later, the bumpy pavement of Highway 441 — the main artery between downtown Franklin and Mount Cullowhee, gives way to gravel or dirt roads, most barely wide enough for two cars. In this harsh terrain, tires and brakes wear out quickly. Engines strain — and sometimes die — mid-climb. Mt. Cullowhee’s latest victims often litter the narrow highway shoulder, their abandoned metal carcasses awaiting a tow.

The Dodge came to a similar end one day in 2016 when its engine bit the dust. Towing and repairs would have cost more than the car was worth, and anyway, it was money that Donna didn’t have. So she left the Dodge — and the tower’s $300 bill — at the bottom of the mountain.

Cars are a necessity in Franklin, a town of nearly 4,000 where the median income is $33,761, far below the county’s median income of $45,507. Almost anything from the Ingels to Dollar General is at least 15 to 20 minutes away in good weather.

Like many rural areas of the state, the county’s public transit system is irregular at best, with dedicated weekday downtown loops. Those who, like Donna and C., lived in Franklin’s outskirts, have to schedule a ride to town at least a week in advance. And if there weren’t enough drivers or vehicles for all the rides that day, the transit authority would cancel its scheduled rides.

The faded Olds wagon was an unexpected lifeline for Donna, who often cared for seniors at a local nursing home on evenings and Saturdays. Its former owner had been a patient for years, Donna said. A jovial man in his 90s, the patient insisted that she use the cruiser while he was alive, especially when Donna drove his middle-aged daughter around. He sold the car to Donna for a dollar.

It wasn’t long before Donna’s health would upend their lives in ways that not even a nearly free car could remedy.

‘It wasn’t enough’

Donna lived in a perpetual state of depletion. There was never enough money, time or energy.

Her nurse’s aide job demanded physical and mental strength. She’d help patients with bathing, dressing and eating. When seniors were too weak to sit up or stand, Donna would carry them to the tub or wheelchair. Dementia patients needed endless patience.

“One day they’ll know you and you could have a conversation with them,” she said. “And the next day, they’ll scream and holler and want to beat on you cause they don’t know who you are and you’re in their space.”

Donna has had her share of bumps and bruises on the job, and she’s hardly unique.

Certified nursing assistants — often low-income women — get injured on the job more than any other health care profession. Muscle strain, bruises from aggressive patients and accidents are common. In 2004, roughly 65 percent reported more than one injury a year on the job, the National Nursing Assistant Survey shows.

Donna could not afford health insurance. Neither could she afford to take a day off. She treated all her aches, pains and chills in the same way — Tylenol or ibuprofen. Some days, she’d come home at the end of a long day and resort to the most effective painkiller she knew: alcohol.

But in late 2016, nothing seemed to be touching the aches and low-grade fever she suddenly developed. Donna chalked her symptoms up to a cold and continued working. It wasn’t like she had a choice — she needed the money. Two weeks later, when the fever climbed to 104, Donna turned up at Angel’s emergency room drowsy and delirious. The doctors diagnosed her with sepsis — an infection that’s migrated to the bloodstream. The staph infection had also damaged her heart valve, leaving her with shortness of breath. The Tylenol and frequent drinking had permanently scarred her liver. Her blood sugar was almost three times the normal level.

Donna returned to the trailer on Mount Cullowhee roughly two months later, with a repaired heart valve that her new Medicaid coverage paid for. She could not work and money was tighter than ever.

“We were falling behind on rent, but we gave them what we have,” she said. “It wasn’t enough.”

‘All of a sudden, we couldn’t’

Shady Cove trailer park abuts Highway 441, but the property is nearly invisible from the road. Tucked into Mount Cullowhee, the 17-unit park has no sign or billboard announcing its existence. That’s not unusual here. Franklin’s highway billboards are typically reserved for tourist attractions: upscale RV rentals, gem mines and pottery studios. But mountain folk prefer word-of-mouth to billboards. That’s how Donna found out about many of the homes she had rented: from a friend of a friend, a neighbor or a pastor.

The billboards may obscure the vistas but those mountains attract out of towners whose spending is a major boost to the county’s economy, which has a poverty rate of 14.3 percent. The last decade saw a steady increase in visitor spending. By 2019, the most recent year on record, tourist spending hit a record $191.42 million.

The county’s low-income population, however, saw little of that money. North Carolina’s minimum wage is $7.25 an hour, but a single Macon resident with no children would need to make $13.62 an hour to support themselves, according to a Massachusetts Institute of Technology wage calculator. Two adults with no children needed to make $22.04.

Even when Donna and C. both worked, their combined income put them at roughly $17.25 an hour. But Donna, who made $10 an hour, earned the bulk of that income. On good weeks, rent would consume roughly half of C.’s weekly paycheck. If C. was between jobs or only worked a few days that week, they were short on rent.

They would fall behind one week, catch up on the next only to fall down again. Then C.’s diabetes got worse — his eyesight blurred and an ulcer on his right toe made it difficult to stand or walk. He, too, couldn’t work.

“I would always pay as we were paid,” she said. “And then all of a sudden we couldn’t.”

Donna does not remember when she sought help from Macon New Beginnings, the county’s only homeless prevention organization.

New Beginnings helped Donna with one rent payment during that time, she said. A volunteer there also suggested the couple move to Asheville, where shelters and social support agencies are more plentiful. Donna balked at the idea. Franklin is home. She did not want to leave and start over.

Burke, of New Beginnings, declined to speak about specific clients but said that volunteers bring up a move to a larger city with some participants. Last year, he added, the organization helped 116 clients. Of them, roughly 60 remained housed. The rest dropped off the program or became homeless.

“There’s too many needs,” he said. “One person has multiple needs. One organization can’t fulfill that.”

Volunteers tailor their suggestions to client needs, he added. Some clients may need help applying for social security or coming up with a budget, others may need counseling. Clients can also receive $100 to $200, sometimes more, to cover an overdue bill up to once a year. The rest, he said, is up to clients.

“You’ve got to do something for yourself, he added. “I mean, we’re a helping hand, not a handout.”

By October 2019, money was so tight that neither that helping hand nor C.’s income was enough.

‘You can’t live somewhere for free’

The first notice arrived three days after the rent was due. Shady Cove’s property manager, Michael Hilldale, delivered the note in person, tacking on a $25 late fee onto the $145 the couple already owed.

“ … [I]f rent and late fee is NOT paid by 10/11/2019 5:00 p.m. [sic] an eviction will be filed and fees will be added $126.00 [sic],” he wrote.

The $126 would cover the cost of an eviction filing at the Macon County Courthouse, he added.

By the following week, Donna and C. racked up nearly $500 in late fees and missing rent. Hilldale, a long-time property manager who also owns several rental properties, knew that renters who fall behind rarely catch up. Missed rent wasn’t just a problem for the park owners. Hilldale, who is paid a portion of each rent check he collects, lost money too.

“You can’t live someplace for free,” Hilldale said in a phone interview

The first eviction hearing convened at the courthouse at the end of October, but the magistrate dismissed it for insufficient evidence. Hilldale filed a second order just days later. This time, the magistrate sided with him.

Donna and Hilldale disagree on what happened next. Donna says that Hilldale threw away most of the couple’s belongings, except for the things they could load in their car. Hilldale says he gave the couple plenty of time to remove their possessions and did not throw away anything personal. The only other witness to the eviction, according to Donna, was a neighbor whose name she didn’t remember, who has since moved.

What is clear, is that Donna and C. lost some possessions that day, from the red rocker where she’d rocked her grandson to sleep to the ancient DVD player they’d used for watching C.’s favorite action movies to the groceries they purchased with food stamps.

Afterward they loaded the car with blankets, pillows, clothes and a few books. That night, Donna slept in the backseat and C. slept upfront. A mound of stuff — blankets, books, toiletries, clothes and groceries — quickly covered the backseat. Donna moved her pillows and blankets up front.

The worn driver’s seat had just enough room to recline.

This article first appeared on North Carolina Health News and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

North Carolina Health News is an independent, nonpartisan, not-for-profit, statewide news organization dedicated to covering all things health care in North Carolina. Visit NCHN at www.northcarolinahealthnews.org.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.