In Asheville, it’s almost a cliché that the server who’s bringing your appetizer just might have a master’s degree in anthropology — or even a Ph.D. With jobs in short supply and rents sky-high, the story goes, highly educated professionals are reduced to waiting tables as they scramble to make ends meet.

The numbers, though, show a somewhat more nuanced picture. The unemployment rate in the Asheville metropolitan statistical area is often the lowest in the state: In October, it sat at a modest 4.4 percent, according to the N.C. Department of Commerce. So the problem seems to be not so much the number but the type of jobs available.

“Job quantity is where we’re doing very well,” says Tom Tveidt, of Syneva Economics, an Asheville-based consulting firm. “We’ve been growing for several years, adding a lot of jobs and doing much better than a lot of places. We’re adding more jobs at a higher pace. We’ve passed our pre-recession totals: The number of new jobs is good.”

In fact, between 2005 and 2014, the job-growth rate in the Asheville metro (comprising Buncombe, Haywood, Henderson and Madison counties) outpaced the nation’s — and took less of a hit during the Great Recession. (There was also massive growth in 2004-05, but that was due to the fact that the metro was expanded to include Haywood and Henderson that year.)

However, continues Tveidt, “The flip side of that is wages. We’re not doing as well as far as wage growth goes. The main reason is because we’ve had such tremendous growth in the leisure and hospitality industries, and those aren’t always the highest-wage jobs.”

Between 2005 and 2014, the Asheville metro added 6,520 food preparation and serving-related jobs — more than in any other category. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, though, these jobs, which account for 13.3 percent of the area’s total employment, pay a median hourly wage of just $8.97 — the lowest of any major employment category.

And after filtering out the higher-wage positions (chefs, head cooks and supervisors), that leaves about 21,520 food industry workers here who don’t make enough from a single restaurant job to live within the city limits.

Taking aim

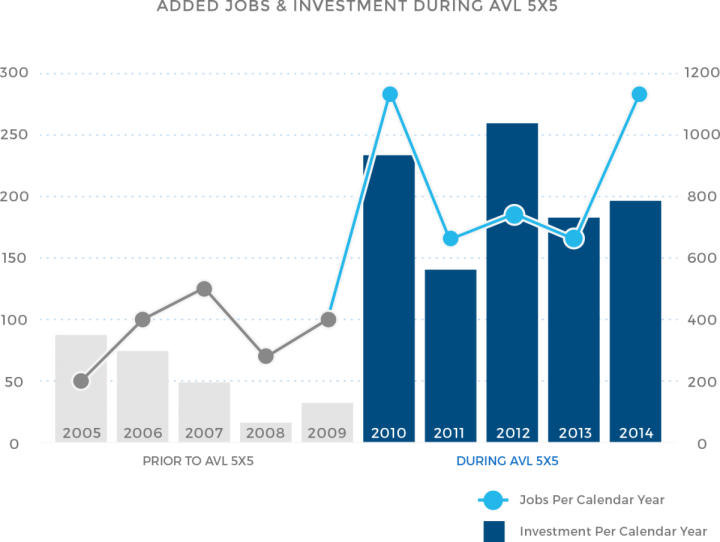

In 2010, the Economic Development Coalition for Asheville-Buncombe County, an arm of the Asheville Area Chamber of Commerce, hatched an ambitious plan to attract higher-wage jobs and industries and diversify Asheville’s economy to create a more sustainable future. The EDC’s AVL 5×5 campaign aimed to bring in 5,000 jobs and $500 million in capital investment over the next five years.

Between 2010 and 2015, the program focused on expanding opportunities in advanced manufacturing, science and technology, health care, and arts and culture — and that strategy paid off. It brought in 33 companies, $1 billion in capital investment and 2,860 new jobs paying an average annual salary of $44,672. And if you include “indirect jobs” (created to provide support services to the direct ones) and “induced jobs” (those created by the broader economic impact of the direct ones), it bumps up the total tally to 6,385 additional positions, according to the EDC.

Many local employers pledged to add substantial numbers of jobs, not all of which are yet in place. Linamar announced an unequaled 800 additional positions. Arvato Digital Services promised 408, Nypro signed on for 156, and BorgWarner announced 154. New Belgium Brewing sited its East Coast facility here and also committed to 154 future jobs. Thermo Fisher Scientific agreed to add 110, and AvL Technologies announced 90 new jobs — and those are only a few of the top names. Some of these companies were offered financial incentives tied to providing the promised jobs within a specified period.

Collaboration was a key to the project’s success, says Ben Teague, the coalition’s executive director. “We spoke with the community, and they told us, ‘This is the direction we want it to go,’” notes Teague, who headed the initiative. “Some communities don’t really know who they are and what they’re good at, but including them gave us a direction. We discovered who we are and how we should market ourselves to the world. There’s a call out for smarter, higher-wage jobs.”

Meanwhile, on Sept. 17, the EDC unveiled AVL 5×5 Vision 2020, a blueprint for the next five years. This time around, the goal is to bring in 3,000 new direct jobs with an average annual wage of $50,000, $650 million in new capital investment and 50 new high-growth companies.

Refining the goals of the original plan, Vision 2020 targets eight different employment areas: aerospace, automotive, breweries and their supply chains, climate science, digital media/information technologies, divisional and regional headquarters, micro-electromechanical systems, and recreation technology/outdoor equipment. It also seeks to develop Asheville’s rich existing talent pool by empowering future entrepreneurs and using them as bait to attract well-paying, national companies that provide high-skill jobs.

That’s all well and good. But how, exactly, does the EDC plan to beat the competition and reel in these much-sought-after employers?

Thinking outside the balance sheet

“There’s a creative problem-solving element to every single project,” chamber President Kit Cramer explains, adding, “This staff is particularly good at that. Understanding the company’s value system and what they prize more than anything else — and trying to appeal to that.”

In New Belgium’s case, says Cramer, “Rather than throwing money at them, which we didn’t have anyway, our staff studied up on them and understood how important their core values were. They made their presentation focused on that — and how Asheville’s values align with the company’s. And as a result, we were able to beat out a much larger, much richer market.”

Other cities’ economic development groups “sell their stuff and not who they are,” Teague maintains. “We sell who we are first, and then find the business case for a company to be here. New Belgium is a good example: They really identified with what they could mean to the area and what the area could mean to the brand — and the quality of life. And we helped them figure out how that could be profitable here.”

After representatives of the Fort Collins, Colo.-based brewery visited Asheville, he explains, EDC staff — playing off the company’s well-known Fat Tire Amber Ale — “secretly ran around putting this bike” in various iconic Asheville settings, taking photos and making each one into a postcard. “See yourself here,” said the postcards, which were then sent to the New Belgium team.

“So it was their brand, their bike, in front of these Asheville locations that they recognized,” says Teague. “And then we just continued to do the work of helping them visualize their future here,” seeking to address some of the many complex details such a major commitment necessarily entails.

On Dec. 18, Reuters reported that the employee-owned company is looking for a buyer that might be willing to pay more than $1 billion. A number of craft breweries have concluded such deals recently, often giving employees a lucrative payday while leaving their jobs intact. In a media release, co-founder and board Chair Kim Jordan said: “New Belgium Brewing’s board of directors has an obligation to have ongoing dialogue with the capital markets, with the goal of making sure that we remain strong as leaders in the craft brewing industry. There is no deal pending at this time.”

Not the next Charlotte

Because land is in short supply in Asheville and Buncombe County and prices are high, the EDC has to make the most efficient use of what sites are available, ensuring that the companies it recruits are really prepared to make a significant investment in this community.

“We have to put more dollars per square foot,” says Teague. “Look at AvL Technologies: great example of a tech company that’s invested millions of dollars in a very small package. And that’s us — that’s who we are, and let’s find the customers that want that. We’re not going to mow down a mountain to attract the next BMW.”

Cramer agrees. “We’re never going to be a Greenville-Spartanburg. We don’t want to be. But we want a piece of the business that’s appropriate for our area.”

In the meantime, however, we still need to get our wages up to the national average — and that also requires creative thinking.

“Higher-wage jobs are going to be in manufacturing and professional business services: legal services, accounting services, computer design, that kind of stuff,” Tveidt explains. “In Asheville, there have been new jobs, like New Belgium, that are higher-paying. But we’ve seen such huge growth in leisure and hospitality that it’s overshadowed the others.”

According to Bureau of Labor Statistics data, 55.3 percent of workers in the Asheville metro make less than $15 an hour. Another 13 percent make less than $16. And only 18 percent of those employed in the four-county statistical area earn more than $20 per hour.

Nationally, an estimated 33.6 percent of workers earn more than $20 an hour, meaning Asheville is significantly behind the curve. People do tend to earn more in bigger cities, partly to offset a higher cost of living. Still, Asheville’s relatively high cost of living leaves many local workers in a bind.

“There isn’t a magic ‘Here’s what a city should have’ ratio of high- to low-wage jobs,” says Tveidt. “Obviously, our leisure and hospitality industries are huge. That’s something we’ve been good at. So it’s sort of lopsided in that respect.”

These days, he speculates, “It might be more a game of catch-up, just trying to get the right balance and get more of those high-wage jobs into the area. But it’s sort of a symptom of our success: The Asheville brand is so popular now, and that’s why we see all these new hotels coming in. Many communities would die to have the number of jobs that we have, because they don’t have any jobs at all. Some areas aren’t even close to having their pre-recession jobs back, and we flew right past those years back.”

So when people think of “the waiter that has the Ph.D.,” says Cramer, “The question is: What do they have the Ph.D. in? … I’m sure anthropology is a very interesting area of study, but it’s not superlucrative. There are lots of available jobs right now … at every skill level in the book. … But it requires that you figure out what’s available and equip yourself for it.”

Economic climate change

One promising niche industry, notes Teague, has been hidden in plain sight for years.

“The Weather Channel started in 1980 in Atlanta, and really, it didn’t become pervasive until the early ’90s. But now it’s a multibillion-dollar industry,” he points out. “It used to be, you’d turn on the radio and it would be like, ‘The weather in Asheville is 80 degrees’ — and that was it. But now weather is so consumable for people.”

And that’s what Teague and his EDC colleagues believe Asheville could do for the future of commercial climate science.

The National Centers for Environmental Information maintains the world’s largest archive of weather data, spanning more than 150 years. Formerly known as the National Climatic Data Center, the Asheville branch is one of four such facilities nationwide.

“There’s 16 Nobel laureates working on this. Those scientists can see what the effect of climate is and visualize what that data means,” notes Teague. “We’re standing in 1980 Atlanta right now, and there’s this huge opportunity before us. You know: ‘Hey, I’m getting married in five months. What would the weather potentially be like?’ That’s consumable and personal for people.”

And it’s all already happening in 2,500 square feet worth of offices in the Veach-Baley Federal Complex on Patton Avenue.

But that, after all, is classic Asheville: big dreams in confined quarters.

Big little Asheville

“I’ve referred to this place as being cosmopolitan in a very small package,” Cramer observes. “It lives larger than it is. So we’re hoping that covering a great critical mass of particular industries … makes it easier to find jobs. This whole country is going to be competing because of the demographic shift that’s occurring: the aging out of baby boomers. We’re going to have to all be competitive. The thing that we have on our side is that we have a tremendously beautiful, cool, fun place that’s attractive” to businesses and talented individuals alike.

And although Asheville’s wages are below the national average now, “Those wage rates will take care of themselves over time,” Cramer maintains. In the past, she points out, “There wasn’t really a mix of industry. We’re hoping that, by having a stronger mix, we’re going to create a stronger economy, and that’ll help address the wage issue.”

In the meantime, while the gap between Asheville-area wages and the cost of living is certainly notable, it may not be as bad as we tend to think, says Chris Bell, chair of UNC Asheville’s economics department.

Asheville’s cost of living, he notes, is “only slightly above the national average. But our perception is formed by the fact that we’re in the Southeast, which has generally lower prices. Asheville has slightly higher prices when we’re comparing ourselves to Charlotte and Fayetteville — which are below the national average.”

The problem, says Bell, is really a question of supply and demand. “You can pay people less, because there’s more people that want to live here, relative to other places.” Employers, he explains, “are the suppliers of labor, and the people moving here are on the demand side. We have greater demand here … and we can’t expand our supply easily.”

This, though, is such a common phenomenon, he notes, that economists have even coined an unofficial name for it: “eating scenery.”

Most employers, continues Bell, “have to pay people based on what people are paid in other places.” But, “If you’re in a place where people would like to live, you don’t have to bribe them as much to get them there. Workers will come here for less, simply because it’s Asheville.”

Building a skill set

Bell also disputes the EDC’s contention that recruiting new employers will necessarily address the problem.

“That’s not going to change by bringing in new companies,” he predicts. “For any equivalent job, they’re typically not going to have to pay as much as they would in a place that’s not as attractive. … How many people do you know that have just quit their jobs and moved here? They’re desperate when they get here: They take what they can get. And there are lots and lots of people willing to do that. Asheville has a huge supply of people who want to work, and that’s not going to go away.”

Teague begs to differ, however. The more high-skill jobs Asheville has, he believes, the more employers that are already here will have to offer to attract the skilled professionals they need. “When your choices are Austin, San Francisco or Asheville, someone has to pay a good wage in order to get that competitive skill,” he argues.

So, for the Vision 2020 initiative, a key strategy is “making sure that our people have national-level skills.” And that means working with local educational institutions to ensure that the next generation of Ashevilleans has what it takes to land those well-paying jobs.

But it also means getting young people excited about the kinds of jobs the EDC is trying to bring in.

Today’s students, Teague maintains, want to be involved with something big. “The pitch of ‘Oh, this is not your father’s manufacturing’ doesn’t work. However, the pitch of ‘You can work on groundbreaking problems; you can solve problems for the world’ — that works. I think manufacturing can have that same message.” To that end, he proposes getting students involved in helping solve complex manufacturing issues “to see what kind of brilliant ideas these kids come up with.”

“But it’s not just the manufacturing sector,” he notes. In Buncombe County alone, “You could find 50-60 tech jobs available right at this moment. And I’ve got another 500 with potential companies coming here. That’s a strong pipeline of tech jobs.”

And for those who lack the skills to qualify for those positions, “Our workforce training programs are designed to meet the short-term training of almost every sector we have in our area,” says Shelley White, vice president of economic and workforce development at A-B Tech.

Fine, but what about those somewhat older Ph.D. servers who’ve already made a considerable investment in a career path?

“We have some programs that are one day. Some of our training programs are more like a semester in length, but most are not that long,” she notes. And since most of these courses cost $200 or less, “For a pretty low investment, you can change your life.”

Students attending these classes are often on their second or third career, says White. “The average age of students in our regular, college-credit programs is in the high 20s. And the average age in the workforce program is in the high 30s. A lot of times, these classes are what helps them gain the confidence to go back to work, especially if they’ve been in a different career and/or lost their jobs.”

A-B Tech also offers support for aspiring entrepreneurs, another key aspect of the EDC’s strategy. “It’s great for people who either have a business idea or want to talk to resources that can help them,” she explains. “People who’ve had successful careers and then decide they want to follow a passion, set their own hours or go out on their own.”

Blurring the lines

Meanwhile, for all the talk about low-paying tourism jobs, it’s worth noting that without tourism, Asheville wouldn’t have made it onto many national companies’ radar to begin with.

New Belgium, for example, “wanted to be downtown, along the river, with kayaking potential,” says Jack Cecil, president and CEO of Biltmore Farms. As co-chair of the 5×5 campaign, he was involved in recruiting the brewery to Asheville. The company, says Cecil, wanted to be seen as a tourism destination itself. “The depth and breadth of the tourism market here, for them, was a big plus. They wanted to be able to sell the beer and … have the concerts on the water — right next to the greenway, so their employees can bike to work.”

The spillover isn’t limited to a company like New Belgium, either, notes Bell. Increasingly, it’s difficult to pigeonhole jobs in tidy categories, because “the tourism-related fields are creating demand for the nontourism fields. You may not have many tourists buying food at the grocery store across from the VA hospital, but you may have people living off Riceville Road who [shop at that store and] depend on tourism” for their work. So is that grocery clerk employed in tourism or not?”

With more tourists coming here and, partly as a result, more folks moving here, Bell maintains, “Really, anybody’s job is more reliant on tourism.” Restaurants, he explains, “may be for tourists, but you have the construction people come in and build or remodel that restaurant. Is that a tourist job when they do the remodeling? It becomes hard to separate that out.”

The mating game

When you bring in a new employer, says Cecil, “You’re mating the company with the city of Asheville and the community. If you own a business in this town, you give back to the community. Don’t come here if you don’t want to do that.”

But it’s not just up to the company to decide if it meshes well with Asheville, argues Teague: Asheville also has to decide if the business is a good fit.

“If I had all the money in the world, I wouldn’t want a Rolls-Royce,” he says. And the EDC uses that same principle when targeting companies to recruit. The trick is finding “a customer out there that fits who we are.”

Consultant John Karras of TIP Strategies helped the EDC define Asheville’s niche. The wage issue, he maintains, “is one of those problems that you want to have. If you look at Austin, where our firm is based, the wages are comparable to the Dallas and Houston areas. It’s actually a little less in some cases. But it costs a lot more to live here because of the desirability factor.

“When you have a really high-quality place like Asheville, like Austin, like Portland, people are paying a premium to live there. And that’s why it’s so important to focus on attracting higher-wage jobs and incentivizing them, instead of just any job.”

In other words, the very forces that are driving the wages vs. cost of living challenge also help create great opportunities for Asheville.

Instead of worrying about a mass exodus due to a lack of jobs, argues Teague, this community just needs to take advantage of “the economic opportunity that we do have. We understand that there might be growth, and we want to manage and capitalize on that growth to increase our brand’s quality.”

Meanwhile, notes Tveidt, “This is not really a new issue: The idea of ‘Where’s the high-paying jobs?’ has been around forever.” In Asheville, though, “It’s probably been exacerbated because of the successful growth on the tourism side.”

In his view, “We’re actually doing very well. I wouldn’t say ‘most,’ but there are certainly a lot of communities that don’t have enough jobs at all. We have the luxury to talk about wages. We’re not worrying about jobs now: We’re worrying about good jobs.

At the same time, however, “It’s not easy,” Tveidt concedes. “Every community is out there trying to do economic development too. It’s not like somebody comes up with a great idea and it’s going to change tomorrow. It’s a long battle.”

This issue has a larger context as well… The change from the industrial revolution to the technological revolution we are experiencing. Automation of labor is a real threat to the work force. In combating this, a return to hiring people over purchasing machinery is critical. Beat cops replaced with surveillance. Gas station attendants replaced with self serve pumps. The grocery store cashier has been replaced with self service lanes so now one cashier can run 4 check out lanes and that cashier didn’t make a bigger paycheck in the exchange. We must really consider this technological issue when considering future job growth.

Chantal – you described the future yourself. It will be more automation and less humans in the work force.

I’ve had my own saying for a long time regarding controversial medical advances (like the morning-after pill, etc.), which is: “science always wins.”

Well, it certainly appears that technology always wins also. It’s the way of the world.

And the irony of many clamoring for significantly higher minimum wages is that they don’t seem to realize they’ll eventually price themselves out of a job.

Except we won’t need any gas stations if the average person has no car because they have no job. Raising the minimum wage will help provide the consumer class we are desperately losing. Raising the minimum wage is what we must do in a rising tide of inflationary pricing. Groceries, insurance, child care, utilities all rise annually while wage is stagnant. Continuing to tell people to eat cake will only cause a revolt.

Smoke and mirrors, folks. Smoke and mirrors.

Here’s a place to start: how about some degrees at UNC-A that aren’t Fine Arts and Liberal Arts, i.e. “potters and poets”? We have too many of them in Asheville as it is, and most of them wait tables and tend bar while they hope the world discovers that they are the Next Big Thing.

Meanwhile, it is ridiculous that UNCA is right next to Mission, WNC’s regional medical center, yet ADN nurse graduates from A-B Tech have to telecommute or actually commute to Boone, Hickory, Cullowhee and Statesville to earn their Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees.

Let’s stop treating UNCA like a commune of entitled pseudo-intellectuals and use it for something that is actually needed here.

The short term (next ten years or so) situation can be helped by shifting the focus of attracting business to value added organizations vs. service oriented ones. If you focus on retirement services and tourism services you end up with retirees and tourists. While neither are bad neither are productive members of a community. The brewing industry is the only substantial value added business I’m aware of setting up here in Asheville recently. We could revive the associated glass bottling production (remember Gerber). We could support a hops pelletizer facility to foster local hops farming (remember tobacco). These are just a couple value added businesses but they represent the necessary backbone of a sustainable community. The longer term issue of employment vs. technological advance is a much bigger egg to crack and is going to require the complete restructuring of earning money and how money relates to the basic needs of food and shelter. It’s going to be a challenging and sometimes very uncomfortable situation for everybody involved but as we are forced to live in a global economy our standard of living is going to come in line with global norms whether we like it or not. Get ready.

It’s not government’s or the public’s job to focus on particular economic sectors. the market does that with no direction or favoritism from policymakers. That said, the only jobs that Asheville or Buncombe needs more of are homebuilding jobs, all other jobs belong in neighboring counties, not Asheville or Buncombe.

By golly, I just love practical people!

Big Al – I’ve read these comments from you before and it makes sense. Pls keep beating the drum about it as it will eventually get heard by the appropriate people.

Avl Bill – clearly, you pay attention and connect the dots. Very good ideas you have. Your last sentence stopped me in my tracks for a moment as I digested it. “as we are forced to live in a global economy our standard of living is going to come in line with global norms whether we like it or not. Get ready.”

Hadn’t thought about that aspect before but, I believe you are right.

Thanks for the love, but I doubt my drum beats will be heard. UNCA alum and supporters are very entitled and insulated.

That’s only true if we legalize 11 million scabs. If we deport them Americans will have all the jobs, All the housing, and all the American oil, gas, farmland, coal, Iron ore , timber etc. Think how much rent we would save if we deported 11 million.

Asheville already has more jobs than homes which is out of balance and causes long commutes which waste gas, time, and damage the environment. Asheville should discourage jobs and encourage only housing, the jobs are needed where the commuters are coming from, in the neighboring counties, Henderson, Rutherford, McDowell, Yancey, Madison, Haywood and Transylvania. Any Asheville employer who can possibly move should move to one of those counties, to make more room for urban housing, except for homebuilders.