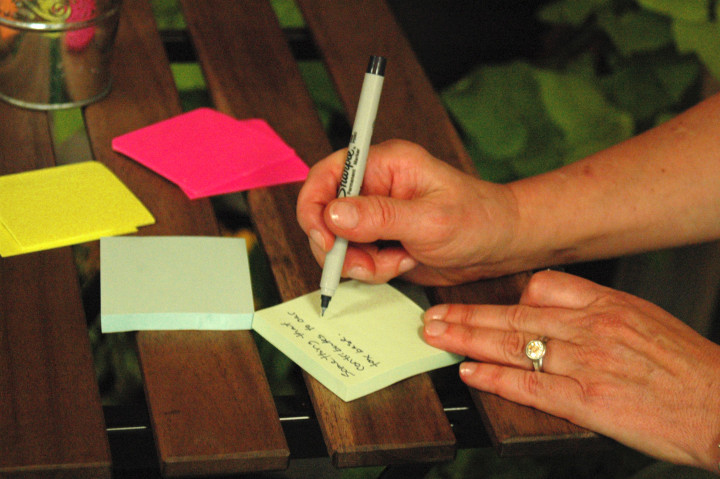

How do you get from the “Pit of Despair” to the “Pit of Hope”? According to the Asheville Design Center, the best strategy is to start by asking everyone for their ideas. Two all-day sessions on June 23 and 28 provided community members with an opportunity to weigh in with ideas for the eventual use of city-owned properties at 68-76 Haywood St. and 33-37 Page Ave. in downtown Asheville. The sessions, which were attended by over 100 people, were held at the former BB&T Building on One West Pack Square.

When asked about origin of the term “Pit of Despair,” Chris Joyell, executive director of the ADC, replies, “I think the city has come to embrace that term because we realized that there is nowhere to go but up.”

The city first began acquiring property in the area facing the U.S. Cellular Center and the Basilica of St. Lawrence in 2002, with the purchase of 33-35 Page Ave. for $850,000. At that time, the city planned to demolish the building to provide access to Battery Park Alley, which would have been blocked by a planned parking deck. A little over a year later, the city purchased three more parcels where the parking deck was to be located. According to public records, in 2003 the city paid $602,000 for 68 Haywood St., $650,000 for 76 Haywood St. and $265,000 for 37 Page Ave. Demolishing existing buildings located on the Haywood Street sites and regrading the area cost $408,320.

When plans for the parking deck ran off the rails, the city ended up leasing the building at 33-35 Page Ave. to Sister Cities for $1 per year. The building, which had been in poor condition when the city bought it, finally reached a state of deterioration that led the city to declare it unsafe for occupancy this spring. In March, City Council budgeted $115,000 for demolishing the structure. The costs of purchasing the properties and demolishing existing buildings total about $2.9 million.

While several potential uses for the site have been considered (including the abandoned parking garage plan, a hotel and a corporate headquarters), controversy and shifting economic conditions dogged City Council efforts to sell the properties to private developers. A campaign calling for a grassy park in the area eventually resulted in Council’s agreement in March to undertake a community visioning process to gather ideas for the space. Council budgeted $15,000 to match an equal amount of private funds to support the effort under the leadership of the ADC.

As far as he knows, Joyell says, this is the first time City Council has asked a local volunteer-based group to assist with planning a project.

“This is the first time I think that the city is really open to allowing the citizens to begin defining that vision for us,” Joyell says. “The ADC’s role is really to help facilitate that; we’re the sponge. We’ll just take in all the information, and then we deliver it to an advisory team.”

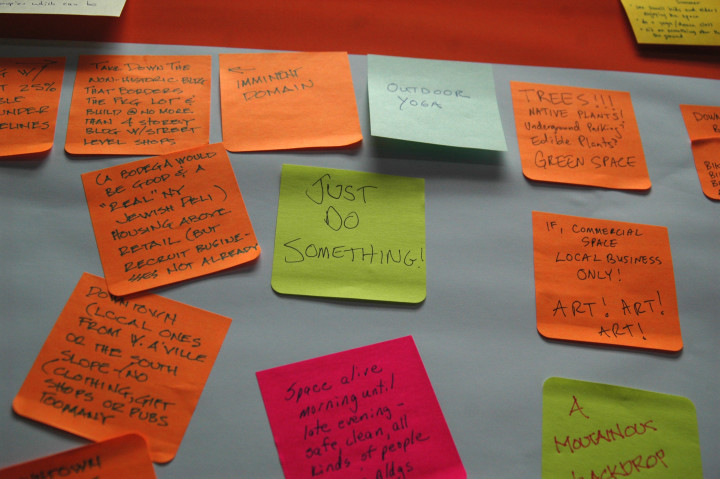

Ideas ranged from an amphitheater to a park to a Ferris wheel.

Joyell says that what people mostly want from the site, whether it’s another business or restaurant, is that it be of local origin and orientation.

“If we build something for the locals, I think it’s going to work for the tourists as well,” he says. “That way we know we are serving locals first.”

The space under consideration is one full acre, and it can fit at least six Pritchard Parks, according to Joyell.

One tool the design center is using to help the public visualize different possibilities for the space is a three-dimensional model.

Joyell explains that planners are open to any and all ideas from the public, but the concept for the entire project is to “let form follow function.” In other words, he and city staff want the public to focus more on what people can do in the area, rather than what they want to see in that space.

“When people come in, the question that we most often get asked here is ‘What’s it gonna be? What are we going to see out there?’” he says. “[But] that, to me, is when you are focusing on the end result: What is the finished form of this park or living space, etc.?”

“What we are saying is that before we get to that, before we start determining what the design is going to be, let’s go all the way back and figure out what the uses are first. Once we understand how the site needs to function, then we’ll form the design,” Joyell explains.

Those attending the public sessions were told there should be no limits on what ideas they come up with and that they should not worry about the budget in putting forward their suggestions.

“I guess at this stage the city has asked us to not include the budget in the considerations, because they want the general public to throw every idea that they have up on our wall and not feel limited,” Joyell says. “I think that we will eventually have to get to that point where the rubber meets the road, and as we take these ideas, we then want to work with City Council to see just how much money we have to work with.”

“Designers like parameters; we like confinement. And that’s a big part of it, the budget we have to work with. For now though, the City Council really wants people to be aspirational as possible and then we’ll apply reality to those ideas,” he continues.

The ADC’s approach originates, Joyell says, with the “power of 10” theory. In its simplest form, the theory posits that, the more there is to do in a space, the more that people will be drawn to the space, which in turn will bring energy, social opportunities and economic benefits to the community.

“When you create a space, if you can create 10 separate uses for that space, and if you try to think about how that space can be used over the four seasons — and even [over the] course of a day: morning, afternoon and night — creating enough uses to keep that space active is going to be the best guarantee of its success,” Joyell says.

According to Joyell, there isn’t a deadline yet for idea submissions. According to the press release that announced the two sessions, there are plans for a future public planning workshop to continue discussions about the area.

For those who were unable to attend the open houses, but still wish to give input, Joyell says to contact him to set up a time to meet at the ADC. He can be reached at (828) 782-7894 or chris@ashevilledesigncenter.org.

“I think we all just want to just get to the end, and be like, ‘Tell me what this thing is going to be,’” Joyell says. “That’s why it requires just a little bit of patience and faith in the process itself. If we really do adhere to it and are we’re transparent about it and are honest about it — wherever we end up, we are going to end up with something great for downtown.”

For previous Xpress coverage of the Haywood Street sites, please see:

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.